Showing posts with label drugs for alcoholism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label drugs for alcoholism. Show all posts

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

Another Look at Acamprosate

The most popular pharmaceutical treatment for alcoholism, explained.

(First published February 17, 2014)

“Occasionally,” reads the opening sentence of a commentary published online earlier this year in Neuropsychopharmacology, “a paper comes along that fundamentally challenges what we thought we knew about a drug mechanism.” The drug in question is acamprosate, and the mechanism of action under scrutiny is the drug’s ability to promote abstinence in alcoholics. The author of the unusual commentary is Markus Heilig, Chief of the Laboratory of Clinical and Translational Studies at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

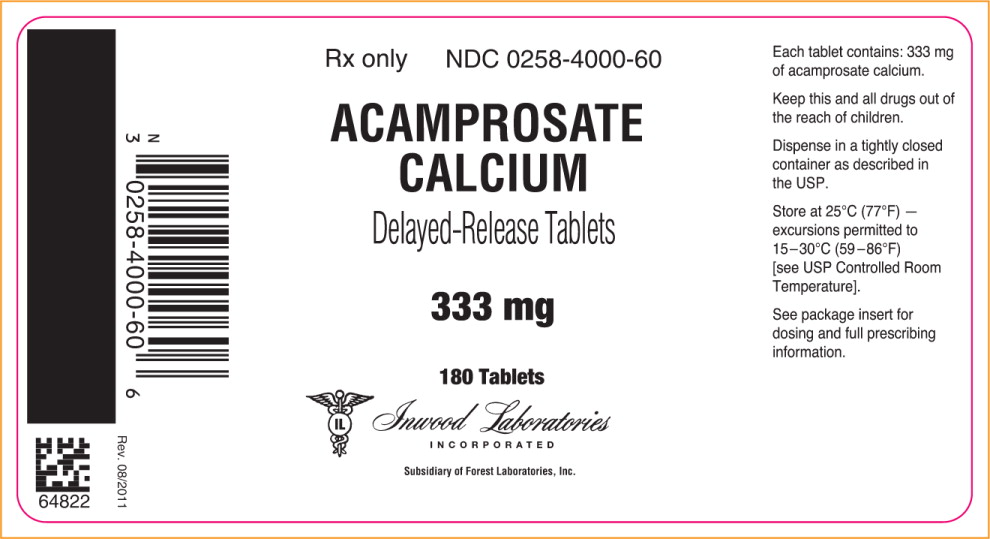

Acamprosate, in use worldwide and currently the most widely prescribed medication for alcohol dependence in the U.S., may work by an entirely different mechanism than scientists have believed on the basis of hundreds of studies over decades. Rainer Spanagel of the Institute of Psychopharmacology at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, led a large research group in revisiting research that he and others had performed on acamprosate ten years earlier. In their article for Neuropsychopharmacology, Spanagel and coworkers concluded that a sodium salt version of acamprosate was totally ineffective in animal models of alcohol-preferring rats.

“Surprisingly,” they write, “calcium salts produce acamprosate-like effects in three animal models…. We conclude that N-acetylhomotaurinate is a biologically inactive molecule and that the effects of acamprosate described in more than 450 published original investigations and clinical trials and 1.5 million treated patients can possibly be attributed to calcium.”

At present, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA] has approved three drugs for alcoholism— Antabuse, naltrexone, plus acamprosate in 2004. In addition, there is considerable clinical evidence behind the use of four other drugs—topiramate, baclofen, ondansetron, and varenicline. Acamprosate as marketed is the calcium salt of N-acetyl-homotaurinate, a close relative of the amino acid taurine. It has also been found effective in European studies.

What did scientists think acamprosate was doing? Various lines of research had linked acamprosate to glutamate transmission. Changes in glutamate transmission have been directly implicated in active alcoholism. A decade ago, the Spanagel group had decided that acamprosate normalized overactive glutamate systems, and hypothesized that acamprosate was modulating GABA transmission. So it became known as a “functional glutamate antagonist.” But specific mechanisms have remained elusive ever since.

Now, as Heilig comments, “the reason it has been difficult to pin down the molecular site of acamprosate action may simply be because it does not exist. Instead, the authors propose that the activity attributed to acamprosate has all along reflected actions of the Ca++ it carries.” As the researcher paper explains it: “N-acetylhomotaurinate by itself is not an active psychotropic molecule…. We have to conclude that the proposed glutamate receptor interactions of acamprosate cannot sufficiently explain the anti-relapse action of this drug.” Further work shows that acamprosate doesn’t interact with glutamate binding sites at all. In other words, calcium appears to be the major active ingredient in acamprosate. Animal studies using calcium chloride or calcium gluconate reduced alcohol intake in animals at rates similar to those seen in acamprosate, the researchers claim.

Subsequently, the researchers revisited the earlier clinical studies, subjected them to secondary analysis, and concluded that “in acamprosate-treated patients positive outcomes are strongly correlated with plasma Ca++ levels. No such correlation exists in placebo-treated patients.” In addition, calcium salts delivered via different carrier drugs replicated the suppression of drinking in the earlier animal findings.

Where there cues pointing toward calcium? The researchers conclude that “calcium sensitivity of the synapse is important for alcohol tolerance development, calcium given intraventricularly significantly enhances alcohol intoxication in a dose-dependent manner,” and “activity of calcium-dependent ion channels modulate alcohol drinking.”

Interestingly, in the late 50s and early 60s, there was a brief period of interest in calcium therapy for the treatment of alcoholism. In 1964, the Journal of Psychology ran an article titled “Intensive Calcium Therapy as an Initial Approach to the Psychotherapeutic Relationship in the Rehabilitation of the Compulsive Drinker.” Now it appears possible that a daily dose of acamprosate is effective for some abstinent alcoholics because it raises calcium plasma levels. Calcium supplements may be in for a round of intensive clinical testing if these findings hold up.

The authors now call for “ambitious randomized controlled clinical trials,” to directly compare “other means of the Ca++ delivery as an approach to treat alcohol addiction. Data in support of a therapeutic role of calcium would open fascinating clinical possibilities.” Indeed it would.

Spanagel R., Vengeliene V., Jandeleit B., Fischer W.N., Grindstaff K., Zhang X., Gallop M.A., Krstew E.V., Lawrence A.J. & Kiefer F. (2013). Acamprosate Produces Its Anti-Relapse Effects Via Calcium, Neuropsychopharmacology, 39 (4) 783-791. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2013.264

Thursday, January 5, 2012

A Drug for Head Lice and Heartworm Shows Promise Against Alcohol Abuse

Unlikely candidate helps alcohol-dependent mice cut back on the sauce.

Say what you will about glutamate-gated chloride channels in the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus—but the one thing you probably wouldn’t say about the cellular channels in parasitic worms is that a drug capable of activating them may prove useful in the treatment of alcoholism and other addictions.

When scientists go looking for drugs to use against addiction, they do not typically begin with a class of drugs that includes a medication for use against head lice and ticks. But that is exactly where the trail led Daryl Davies, co-director of the Alcohol and Brain Research Laboratory at the University of Southern California. Davies and his group were interested in a set of molecules in the brain known as P2X receptors. A subtype of these receptors, involved in ion channel gating, cease to function in the presence of ethanol. The researchers found that if you keep flooding the receptor with alcohol, these ion gates shut down permanently—an example of how alcohol abuse can change the brain.

Another compound that works on the same ion gate is ivermectin, an anti-parasitic medicine used around the world in humans and animals. As it turns out, ivermectin blocks the effect that alcohol has on P2X receptor subtypes. In recent research, the USC team demonstrated that alcohol-dependent mice drank half as much when they were also given ivermectin. This “newly identified alcohol pocket” is a mystery at present. But ivermectin does appear to work primarily on glutamate systems. (See previous post). For now, the researchers can’t say for certain why ivermectin makes mice drink less, but suspect it has something to do with how the brain signals that it’s time to stop drinking. Davies has speculated that a drug like ivermectin could be of use in treatment programs other than “abstinence-based models.” As Suzanne Wu reports in USC Trojan magazine, the team is now at work on other drugs based on ivermectin’s molecular structure. “If there was already a drug that was 95 percent effective, I might not be studying ivermectin,” Davies told the magazine. “I might not even be in the alcohol field. The funding for alcoholism research hasn’t caught up with the magnitude of the consequences of not finding a cure.”

Photo credit: http://www.usapetexpress.com

Friday, January 21, 2011

Personalizing Addiction Medicine

Rather than taking on another broad hunt for the genes controlling the expression of alcoholism, noted addiction researcher Dr. Bankole Johnson and co-workers at the Department of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia took a different tack. The researchers focused, instead, on investigating whether genetic variations among alcoholics might affect their responses to a specific anti-craving medication.

For any addiction, once it has been active for a sustained period, the first-line treatment of the future is likely to be biological. New addiction treatments will come—and in many cases already do come—in the form of drugs to treat drug addiction. Every day, addicts are quitting drugs and alcohol by availing themselves of drug treatments that did not exist fifteen years ago. As more of the biological substrate is teased out, the search for effective approaches narrows along avenues that are more fruitful. This is the most promising, and, without doubt, the most controversial development in the history of addiction treatment.

The researchers were interested in variations in the gene controlling the expression of a serotonin transporter protein. Dr. Johnson’s earlier work had centered on teasing out the influence the serotonin 5-HTT transporter exerts on the development of alcoholism. Previous research had focused attention on the so-called LL and TT variants of this transporter gene. After performing genetic analyses to determine which test subjects were carrying which versions of the gene in question, Dr. Johnson and his colleagues conducted a controlled trial of ondansetron on a randomized group of 283 alcoholics.

The findings were published in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

The findings were published in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Ondansetron is an anti-emetic medication that has shown promise in treating addictions, particularly alcoholism. Ondansetron (trade name Zofran), helps block the nausea of chemotherapy by altering serotonin activity in the GI tract. (Vomiting is a serotonin-mediated reflex.) The scientists found that “individuals with the LL geno-type who received ondansetron had a lower mean number of drinks per day (-1.62) and a higher percentage of days abstinent (11.27%) than those who received placebo.” This put the ondansetron drinkers under five drinks a day. All of the placebo drinkers continued to exceed the five drinks per day mark.

But the strongest difference was found in the group of alcoholics who possessed both the LL and TT genetic variants. The LL/TT alcoholics taking ondansetron “had a lower number of drinks per drinking day (-2.63) and a higher percentage of days abstinent (16.99%) than all other geno-type and treatment groups combined.”

The goal here is straightforward. In an email exchange, Dr. Johnson told me: “I agree that it would be great if we could use a pharmacogenetic approach to study other anti-craving drugs. The idea of providing the right drug to the right person is definitely important for optimizing therapeutic effects and minimizing side-effects.” Here is a video of Dr. Johnson discussing the research, courtesy of the University of Virginia:

It won’t be easy. Such genetic testing is still in its infancy, and complications abound. For example, in an earlier study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Dr. Johnson found that diagnosed patients who received ondansetron over an 11-week period increased their days of abstinence compared to alcoholics on placebo. However, in that study, “The researchers found no differences between ondansetron patients with late-onset alcoholism and those who received placebo.” This suggests that, along with genetic variations, ondansetron’s effectiveness with alcoholics may also depend on the type of alcoholism under consideration: early onset or late onset.

We have a long way to go, but individualized pharmaceutical assistance in the early stages of addiction recovery remains the Holy Grail for many addiction researchers. And hopes are running high.

Johnson, B., Ait-Daoud, N., Seneviratne, C., Roache, J., Javors, M., Wang, X., Liu, L., Penberthy, J., DiClemente, C., & Li, M. (2011). Pharmacogenetic Approach at the Serotonin Transporter Gene as a Method of Reducing the Severity of Alcohol Drinking American Journal of Psychiatry DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050755

Graphics credit: Sergey Ivanov at http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/content/

Monday, July 21, 2008

Drugs for Alcoholism

Different meds for different drinkers

Although there are still only three drugs officially approved by the FDA for the treatment of alcoholism, the research picture is beginning to change. In an article by Greg Miller published in the 11 April 2008 edition of Science, alcoholism researcher Stephanie O'Malley of Yale University said: "We have effective treatments, but they don't help everyone. There's lots of room for improvement."

The medications legally available by prescription for alcoholism are: disulfiram (Antabuse), naltrexone (Revia and Vivitrol), and acamprosate (Campral), the latest FDA-approved entry. A fourth entry, topiramate (Topamax), is currently only approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use against seizures and migraine. The controversial practice of “off-label” prescribing—using a drug for indications that are not formally approved by the FDA—has become so common that Johnson & Johnson said it had no plans to seek formal approval for the use of Topamax as a medicine for addiction. (See my post,"Topamax for Alcoholism: A Closer Look").

Addiction experts are beginning to focus on which treatment drugs work best for different types of alcoholics. Two recent discoveries might help clarify the picture. Psychopharmacologist Charles O'Brien at the University of Pennsylvania reported that alcoholics with a specific variation, or allele, of a prominent opioid receptor gene were more likely to respond positively to treatment with naltrexone. Other work reported in the February 2008 Archives of General Psychiatry came to the same conclusion.

The second research insight builds on a lifetime of work by Robert Cloninger at Washington University in St. Louis. Cloninger discovered that alcoholics come in two basic flavors--Type 1 and Type 2. Type 1, the more common form, develops gradually, later in life, and does not necessarily require structured intervention. Type 1 alcoholics do not always experience the dramatic declines in health and personal circumstances so characteristic of acute alcoholism. These are the people often found straddling the line between alcoholic and problem drinker. In contrast, so-called Type 2 alcoholics are in serious trouble starting with their first taste of liquor during adolescence. Their condition worsens with horrifying speed. They frequently have a family history of violent and antisocial behavior, and they often end up in prison. They are rarely able to hold down normal jobs or sustain workable marriages for long. Type 2s, also known as “familial” or “violent” alcoholics, are likely to have had an alcoholic parent.

Type 1 drinkers, who only get in trouble gradually, are also known as "anxious" drinkers, and research suggests that they may respond better to medicines that alleviate alcohol-related anxiety, such as Lilly's new suppressor of stress hormones, known as LY686017. (See my post, "Drug That Blocks Stress Receptor May Curb Alcohol Craving "). Researchers at the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), working with colleagues at Lilly Research Laboratories and University College in London, announced the discovery of a drug that diminished anxiety-related drug cravings by blocking the so-called NK1 receptor (NK1R). The drug “suppressed spontaneous alcohol cravings, improved overall well-being, blunted cravings induced by a challenge procedure, and attenuated concomitant cortisol responses.”

The NIAAA researchers are making effective use of recent findings about the role played by corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) in the addictive process. CRH is crucial to the neural signaling pathway in areas of the brain involved in both drug reward and stress. As it happens, NK1R sites are densely concentrated in limbic structures of the mid-brain, such as the amygdala, or so-called “fear center.”

Researchers are understandably excited about these developing insights. Psychopharmacologist Rainer Spanagel of Germany's Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim called such research "a milestone in pharmacogenetics." In Greg Miller's Science article, Willenbring of NIAAA predicted that the field is poised for a "Prozac moment," marked by the discovery of "a medication that's perceived as effective, that's well-marketed by a pharmaceutical company, and that people receive in a primary-care setting or general-psychiatry setting."

In "Days of Wine and Roses, " the 1960s film about alcoholism, Jack Lemmon played a character who embodied Type 2 characteristics--early trouble with alcohol, extreme behavioral dysregulation, poor long-term planning, and a hollow leg. His wife, played by Lee Remick, demonstrates the slower, more measured descent from problem drinking into clinical alcoholism that characterizes Type 1 alcoholics. Research now suggests that Lee Remick might do better on LY686017, while Jack Lemmon's character would be a promising candidate for treatment with naltrexone.

Photo credit: About Alcohol Information

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)