Showing posts with label acamprosate. Show all posts

Showing posts with label acamprosate. Show all posts

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

Another Look at Acamprosate

The most popular pharmaceutical treatment for alcoholism, explained.

(First published February 17, 2014)

“Occasionally,” reads the opening sentence of a commentary published online earlier this year in Neuropsychopharmacology, “a paper comes along that fundamentally challenges what we thought we knew about a drug mechanism.” The drug in question is acamprosate, and the mechanism of action under scrutiny is the drug’s ability to promote abstinence in alcoholics. The author of the unusual commentary is Markus Heilig, Chief of the Laboratory of Clinical and Translational Studies at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

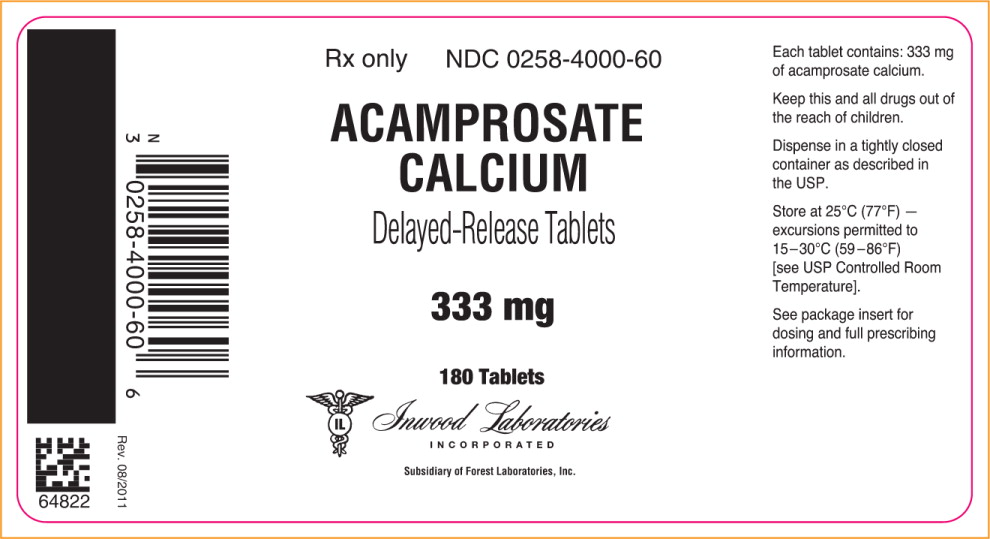

Acamprosate, in use worldwide and currently the most widely prescribed medication for alcohol dependence in the U.S., may work by an entirely different mechanism than scientists have believed on the basis of hundreds of studies over decades. Rainer Spanagel of the Institute of Psychopharmacology at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, led a large research group in revisiting research that he and others had performed on acamprosate ten years earlier. In their article for Neuropsychopharmacology, Spanagel and coworkers concluded that a sodium salt version of acamprosate was totally ineffective in animal models of alcohol-preferring rats.

“Surprisingly,” they write, “calcium salts produce acamprosate-like effects in three animal models…. We conclude that N-acetylhomotaurinate is a biologically inactive molecule and that the effects of acamprosate described in more than 450 published original investigations and clinical trials and 1.5 million treated patients can possibly be attributed to calcium.”

At present, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA] has approved three drugs for alcoholism— Antabuse, naltrexone, plus acamprosate in 2004. In addition, there is considerable clinical evidence behind the use of four other drugs—topiramate, baclofen, ondansetron, and varenicline. Acamprosate as marketed is the calcium salt of N-acetyl-homotaurinate, a close relative of the amino acid taurine. It has also been found effective in European studies.

What did scientists think acamprosate was doing? Various lines of research had linked acamprosate to glutamate transmission. Changes in glutamate transmission have been directly implicated in active alcoholism. A decade ago, the Spanagel group had decided that acamprosate normalized overactive glutamate systems, and hypothesized that acamprosate was modulating GABA transmission. So it became known as a “functional glutamate antagonist.” But specific mechanisms have remained elusive ever since.

Now, as Heilig comments, “the reason it has been difficult to pin down the molecular site of acamprosate action may simply be because it does not exist. Instead, the authors propose that the activity attributed to acamprosate has all along reflected actions of the Ca++ it carries.” As the researcher paper explains it: “N-acetylhomotaurinate by itself is not an active psychotropic molecule…. We have to conclude that the proposed glutamate receptor interactions of acamprosate cannot sufficiently explain the anti-relapse action of this drug.” Further work shows that acamprosate doesn’t interact with glutamate binding sites at all. In other words, calcium appears to be the major active ingredient in acamprosate. Animal studies using calcium chloride or calcium gluconate reduced alcohol intake in animals at rates similar to those seen in acamprosate, the researchers claim.

Subsequently, the researchers revisited the earlier clinical studies, subjected them to secondary analysis, and concluded that “in acamprosate-treated patients positive outcomes are strongly correlated with plasma Ca++ levels. No such correlation exists in placebo-treated patients.” In addition, calcium salts delivered via different carrier drugs replicated the suppression of drinking in the earlier animal findings.

Where there cues pointing toward calcium? The researchers conclude that “calcium sensitivity of the synapse is important for alcohol tolerance development, calcium given intraventricularly significantly enhances alcohol intoxication in a dose-dependent manner,” and “activity of calcium-dependent ion channels modulate alcohol drinking.”

Interestingly, in the late 50s and early 60s, there was a brief period of interest in calcium therapy for the treatment of alcoholism. In 1964, the Journal of Psychology ran an article titled “Intensive Calcium Therapy as an Initial Approach to the Psychotherapeutic Relationship in the Rehabilitation of the Compulsive Drinker.” Now it appears possible that a daily dose of acamprosate is effective for some abstinent alcoholics because it raises calcium plasma levels. Calcium supplements may be in for a round of intensive clinical testing if these findings hold up.

The authors now call for “ambitious randomized controlled clinical trials,” to directly compare “other means of the Ca++ delivery as an approach to treat alcohol addiction. Data in support of a therapeutic role of calcium would open fascinating clinical possibilities.” Indeed it would.

Spanagel R., Vengeliene V., Jandeleit B., Fischer W.N., Grindstaff K., Zhang X., Gallop M.A., Krstew E.V., Lawrence A.J. & Kiefer F. (2013). Acamprosate Produces Its Anti-Relapse Effects Via Calcium, Neuropsychopharmacology, 39 (4) 783-791. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2013.264

Monday, February 17, 2014

Acamprosate For Alcohol: Why the Research Might Be Wrong

“Occasionally,” reads the opening sentence of a commentary published online last month in Neuropsychopharmacology, “a paper comes along that fundamentally challenges what we thought we knew about a drug mechanism.” The drug in question is acamprosate, and the mechanism of action under scrutiny is the drug’s ability to promote abstinence in alcoholics. The author of the unusual commentary is Markus Heilig, Chief of the Laboratory of Clinical and Translational Studies at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

Acamprosate, in use worldwide and currently the most widely prescribed medication for alcohol dependence in the U.S., may work by an entirely different mechanism than scientists have believed on the basis of hundreds of studies over decades. Rainer Spanagel of the Institute of Psychopharmacology at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, led a large research group in revisiting research that he and others had performed on acamprosate ten years earlier. In their article for Neuropsychopharmacology, Spanagel and coworkers concluded that a sodium salt version of acamprosate was totally ineffective in animal models of alcohol-preferring rats.

“Surprisingly,” they write, “calcium salts produce acamprosate-like effects in three animal models…. We conclude that N-acetylhomotaurinate is a biologically inactive molecule and that the effects of acamprosate described in more than 450 published original investigations and clinical trials and 1.5 million treated patients can possibly be attributed to calcium.”

At present, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA] has approved three drugs for alcoholism— Antabuse, naltrexone, plus acamprosate in 2004. In addition, there is considerable clinical evidence behind the use of four other drugs—topiramate, baclofen, ondansetron, and varenicline. Acamprosate as marketed is the calcium salt of N-acetyl-homotaurinate, a close relative of the amino acid taurine. It has also been found effective in European studies.

What did scientists think acamprosate was doing? Various lines of research had linked acamprosate to glutamate transmission. Changes in glutamate transmission have been directly implicated in active alcoholism. A decade ago, the Spanagel group had decided that acamprosate normalized overactive glutamate systems, and hypothesized that acamprosate was modulating GABA transmission. So it became known as a “functional glutamate antagonist.” But specific mechanisms have remained elusive ever since.

Now, as Heilig comments, “the reason it has been difficult to pin down the molecular site of acamprosate action may simply be because it does not exist. Instead, the authors propose that the activity attributed to acamprosate has all along reflected actions of the Ca++ it carries.” As the researcher paper explains it: “N-acetylhomotaurinate by itself is not an active psychotropic molecule…. We have to conclude that the proposed glutamate receptor interactions of acamprosate cannot sufficiently explain the anti-relapse action of this drug.” Further work shows that acamprosate doesn’t interact with glutamate binding sites at all. In other words, calcium appears to be the major active ingredient in acamprosate. Animal studies using calcium chloride or calcium gluconate reduced alcohol intake in animals at rates similar to those seen in acamprosate, the researchers claim.

Subsequently, the researchers revisited the earlier clinical studies, subjected them to secondary analysis, and concluded that “in acamprosate-treated patients positive outcomes are strongly correlated with plasma Ca++ levels. No such correlation exists in placebo-treated patients.” In addition, calcium salts delivered via different carrier drugs replicated the suppression of drinking in the earlier animal findings.

Where there cues pointing toward calcium? The researchers conclude that “calcium sensitivity of the synapse is important for alcohol tolerance development, calcium given intraventricularly significantly enhances alcohol intoxication in a dose-dependent manner,” and “activity of calcium-dependent ion channels modulate alcohol drinking.”

Interestingly, in the late 50s and early 60s, there was a brief period of interest in calcium therapy for the treatment of alcoholism. In 1964, the Journal of Psychology ran an article titled “Intensive Calcium Therapy as an Initial Approach to the Psychotherapeutic Relationship in the Rehabilitation of the Compulsive Drinker.” Now it appears possible that a daily dose of acamprosate is effective for some abstinent alcoholics because it raises calcium plasma levels. Calcium supplements may be in for a round of intensive clinical testing if these findings hold up.

The authors now call for “ambitious randomized controlled clinical trials,” to directly compare “other means of the Ca++ delivery as an approach to treat alcohol addiction. Data in support of a therapeutic role of calcium would open fascinating clinical possibilities.” Indeed it would.

Spanagel R., Vengeliene V., Jandeleit B., Fischer W.N., Grindstaff K., Zhang X., Gallop M.A., Krstew E.V., Lawrence A.J. & Kiefer F. (2013). Acamprosate Produces Its Anti-Relapse Effects Via Calcium, Neuropsychopharmacology, 39 (4) 783-791. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2013.264

Monday, November 12, 2012

Short Subjects

Brief news on drugs and addiction.

The editorial staff at Addiction Inbox (see photo), occasionally finds itself overwhelmed with news and opinion worth broadcasting. Hence, this bullet list of drug/alcohol related news from recent weeks:

• Children with heavy alcohol exposure show decreased brain plasticity, according to recent research on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FAS) using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. The research, supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), included 70 children heavily exposed to alcohol in utero. According to NIAAA, the children showed “lost cortical volume,” described in the study as a pattern of static growth “most evident in the rear portions of the brain—particularly the parietal cortex, which is thought to be involved in selective attention and producing planned movement.”

• Combining medications for a better outcome is a staple of medical practice. So it’s not surprising to see the same thing being investigated in addiction treatment. Scientists evaluating medications for alcoholism have found that in some cases, mixing the medicine gives better outcomes. In two separate trials, naltrexone proved to be a more effective treatment for alcoholism when combined with either acamprosate (reported in Addiction), or baclofen (as detailed by Dr Mark Gold at the recent meeting of the Society for Neuroscience). In the Addiction study, the authors concluded that “acamprosate has been found to be slightly more efficacious in promoting abstinence and naltrexone slightly more efficacious in reducing heavy drinking and craving,” which suggests the possibility of using different drugs at different stages of recovery for maximum benefit. In preliminary work on baclofen, some researchers now claim that combining it with naltrexone often leads to better outcomes.

• Every year at about this time, the rumors start flying: Did you hear that Amsterdam is closing its marijuana coffee shops? This breathless annual announcement is never true, and this year, despite all the fuss over “weed passes” and border skirmishes over drug traffic in the south of the Netherlands, Amsterdam’s mayor recently announced that he has no attention of closing the roughly 200 cannabis shops in his city by year’s end, as originally mandated by the now-defunct conservative government. In addition, rumors are flying that the incoming cabinet of Prime Minister Mark Rutte is already backing away from the previous government’s position on banning foreigners from the shops, according to a New York Times report. “Changes to the new policy have not been finalized,” according to a spokesperson for the Dutch Justice Ministry, quoted in the Times. Rutte himself has hinted that the ban may remain intact, but that local councils may be allowed to override that decision—an outcome not untypical of Dutch politics. “I’m guessing that behind the curtains, it’s already been arranged,” said Michael Veling of the Dutch Cannabis Retailers Association.

• Here’s a finding you can easily test for yourself. Conduct a conversation with a heavily intoxicated chronic drinker. Introduce ironic, “wink-wink” comments into the exchange. Really lay on the irony. And then sit back and watch most of it sail right by your drunk and maddeningly literal companion. And now science is attempting to confirm it: A modest recent study in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research says that “drinking too much alcohol can interfere with men’s feelings of empathy and understanding of irony.” 22 men in an alcoholic treatment program read a series of stories ending with either an ironic comment or a straightforward one. Chronic heavy drinkers identified ironic sentences 63 % of the time, compared to a group of non-alcoholics, who identified 90 % of the ironic comments. Lead researcher Simona Amenta said in a press release that the results may mean that alcoholics “tend to underestimate negative emotions; it also suggests that the same situation might be read in a totally different way by an alcoholic individual and another person.” Ya think?

Photo Credit: http://www.globaljournalist.org/

Labels:

acamprosate,

addiction drugs,

alcohol,

baclofen,

fetal alcohol,

irony,

naltrexone

Monday, January 2, 2012

A Few Words About Glutamate

Meet another major player in the biology of addiction.

The workhorse neurotransmitter glutamate, made from glutamine, the brain’s most abundant amino acid, has always been a tempting target for new drug development. Drugs that play off receptors for glutamate are already available, and more are in the pipeline. Drug companies have been working on new glutamate-modulating antianxiety drugs, and a glutamate-active drug called acamprosate, which works by occupying sites on glutamate (NMDA) receptors, has found limited use as a drug for alcohol withdrawal after dozens of clinical trials.

Glutamine detoxifies ammonia and combats hypoglycemia, among other things. It is also involved in carrying messages to brain regions involved with memory and learning. An excess of glutamine can cause neural damage and cell death, and it is a prime culprit in ALS, known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. In sodium salt form, as pictured---> it is monosodium glutamate, a potent food additive. About half of the brain’s neurons are glutamate-generating neurons. Glutamate receptors are dense in the prefrontal cortex, indicating an involvement with higher thought processes like reasoning and risk assessment. Drugs that boost glutamate levels in the brain can cause seizures. Glutamate does most of the damage when people have strokes.

The receptor for glutamate is called the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. Unfortunately, NMDA antagonists, which might have proven to be potent anti-craving drugs, cannot be used because they induce psychosis. (Dissociative drugs like PCP and ketamine are glutamate antagonists.) Dextromethorphan, the compound found in cough medicines like Robitussin and Romilar, is also a weak glutamate inhibitor. In overdose, it can induce psychotic states similar to those produced by PCP and ketamine. Ely Lilly and others have looked into glutamate-modulating antianxiety drugs, which might also serve as effective anti-craving medications for abstinent drug and alcohol addicts.

As Jason Socrates Bardi at the Scripps Research Institute writes: "Consumption of even small amounts of alcohol increases the amount of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens area of the brain—one of the so-called ‘reward centers.’ However, it is most likely that the GABA and glutamate receptors in some of the reward centers of the basal forebrain—particularly the nucleus accumbens and the amygdala—create a system of positive reinforcement.”

Glutamate receptors, then, are the “hidden” receptors that compliment dopamine and serotonin to produce the classic “buzz” of alcohol, and to varying degrees, other addictive drugs as well. Glutamate receptors in the hippocampus may also be involved in the memory of the buzz.

Writing in The Scientist in 2002, Tom Hollon made the argument that “glutamate's role in cocaine dependence is even more central than dopamine's.” Knockout mice lacking the glutamate receptor mGluR5, engineered at GlaxoSmithKline, proved indifferent to cocaine in a study published in Nature.

In an article for Neuropsychology in 2009, Peter Kalivas of the Medical University of South Carolina and coworkers further refined the notion of glutamine-related addictive triggers: "Cortico-striatal glutamate transmission has been implicated in both the initiation and expression of addiction related behaviors, such as locomotor sensitization and drug-seeking," Kalivas writes. "While glutamate transmission onto dopamine cells in the ventral tegmental area undergoes transient plasticity important for establishing addiction-related behaviors, glutamatergic plasticity in the nucleus accumbens is critical for the expression of these behaviors."

The same year, in Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, Kalivas laid out his “glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction.”

A failure of the prefrontal cortex to control drug-seeking behaviors can be linked to an enduring imbalance between synaptic and non-synaptic glutamate, termed glutamate homeostasis. The imbalance in glutamate homeostasis engenders changes in neuroplasticity that impair communication between the prefrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens. Some of these pathological changes are amenable to new glutamate- and neuroplasticity-based pharmacotherapies for treating addiction.

This kind of research has at least a chance of leading in the direction of additional candidates for anti-craving drugs, without which many addicts are never going to successfully treat their disease.

Graphics credit: http://cnunitedasia.en.made-in-china.com/

Labels:

acamprosate,

addiction,

dopamine,

glutamate,

glutamine,

neuroplasticity,

nucleus accumbens

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Why are Treatment Centers Afraid of Anti-Craving Medications?

Using What Works

Why do so many drug treatment centers continue to shun science by ignoring medications that ease the burden of withdrawal for many addicts? That’s the question posed in an article by Alison Knopf in the May-June issue of Addiction Professional, titled “The Medication Holdouts.”

“Nowhere else in medicine,” Knopf writes, “are the people who treat a condition so suspicious of the very medications designed to help the condition in which they specialize.”

Acamprosate, a drug used to treat alcoholism, is a good case in point. A dozen European studies examining thousands of alcohol test subjects found that the drug increased the number of days that most subjects were able to remain abstinent. But when a German drug maker decided to market the drug in the U.S., fierce advocates for drug-free addiction therapy came out in force, even though the drug was ultimately approved for use.

Disulfiram, naltrexone, acamprosate, methadone, buprenorphine—the evidence for all of them is solid. Knopf cites the case of buprenorphine:

“‘There are scores of peer-reviewed journal articles that evaluate the success of buprenorphine,’ says Nicholas Reuter, MPH, senior public health adviser in the Division of Pharmacologic Therapies at the federal Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). ‘It's well established that the data and the evidence are there. Not treating patients with a medication consigns most of them to relapse, adds Reuter. While some opioid-addicted patients, as many as 20 percent, do respond to abstinence-based therapy, ‘That still leaves us with the 80 percent who don't,’ he says.”

Dr. Charles O'Brien, one the nation’s most respected addiction professionals and a Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, is incensed that anti-craving medications are not more widely used. “It's unethical not to use medications,” he says. “This is a subject that I feel very strongly about.” O’Brien told Addiction Professional he no longer cares who he offends on the subject. “If you're discouraging people from taking medications, you are behaving in an unethical way; you are depriving your patients of a way to turn themselves around. Just because you don't like it doesn't mean you have to keep your patients away from it.”

And at the Association for Addiction Professionals, “the prevailing philosophy is pro-medication,” Knopf writes. Misti Storie, education and training consultant for the group, told Knopf that the “disconnect” at treatment centers is due to a “lack of education about the connection between biology and addiction.” Counselors working in centers that do not allow anti-craving medications are in a tough spot, Storie acknowledged.

It is continually astonishing that treatment centers--where the primary goal is supposed to be the prevention of relapse, even though the success rate remains abysmal--would spurn medications that often help to accomplish precisely that goal. Relapse rates hover around 80%, by an amalgam of estimates, so it’s not like rehabs are wildly successful at what they do. What’s really behind the resistance?

What stands between many addicts and the new forms of treatment is “pharmacological Calvinism.” I would love to claim this term as my own, but it was coined by Cornell University researcher Gerald Klerman. Pharmacological Calvinism may be defined as the belief that treating any psychological symptoms with a pill is tantamount to ethical surrender, or, at the very least, a serious failure of will. As Peter Kramer quoted Klerman in Listening to Prozac: If a drug makes you feel better, then by definition “somehow it is morally wrong and the user is likely to suffer retribution with either dependence, liver damage, or chromosomal change, or some other form of medical-theological damnation.”

Photo credit: www.life123.com

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)