Showing posts sorted by date for query psychosis. Sort by relevance Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by date for query psychosis. Sort by relevance Show all posts

Tuesday, July 21, 2015

Marijuana Deconstructed

What's In Your Weed?

Australia has one of the highest rates of marijuana use in the world, but until recently, nobody could say for certain what, exactly, Australians were smoking. Researchers at the University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales recently analyzed hundreds of cannabis samples seized by Australian police, and put together comprehensive data on street-level marijuana potency across the country. They sampled police seizures and plants from crop eradication operations. The mean THC content of the samples was 14.88%, while absolute levels varied from less than 1% THC to almost 40%. Writing in PLoS one, Wendy Swift and colleagues found that roughly ¾ of the samples contained at least 10% total THC. Half the samples contained levels of 15% or higher—“the level recommended by the Garretsen Commission as warranting classification of cannabis as a ‘hard’ drug in the Netherlands.”

In the U.S., recent studies have shown that THC levels in cannabis from 1993 averaged 3.4%, and then climbed to THC levels in 2008 of almost 9%. By 2015, marijuana with THC levels of 20% were for sale in Colorado and Washington.

CBD, or cannabidiol, another constituent of cannabis, has garnered considerable attention in the research community as well as the medical marijuana constituency due to its anti-emetic properties. Like many other cannabinoids, CBD is non-psychoactive, and acts as a muscle relaxant as well. CBD levels in the U.S. have remained consistently low over the past 20 years, at 0.3-0.4%. In the Australian study, about 90% of cannabis samples contained less than 0.1% total CBD, based on chromatographic analysis, although some of the samples had levels as high as 6%.

The Australian samples also showed relatively high amounts of CBG, another common cannabinoid. CBG, known as cannabigerol, has been investigated for its pharmacological properties by biotech labs. It is non-psychoactive but useful for inducing sleep and lowering intra-ocular pressure in cases of glaucoma.

CBC, yet another cannabinoid, also acts as a sedative, and is reported to relieve pain, while also moderating the effects of THC. The Australian investigators believe that, as with CBD, “the trend for maximizing THC production may have led to marginalization of CBC as historically, CBC has sometimes been reported to be the second or third most abundant cannabinoid.”

Is today’s potent, very high-THC marijuana a different drug entirely, compared to the marijuana consumed up until the 21st Century? And does super-grass have an adverse effect on the mental health of users? The most obvious answer is, probably not. Recent attempts to link strong pot to the emergence of psychosis have not been definitive, or even terribly convincing. (However, the evidence for adverse cognitive effects in smokers who start young is more convincing).

It’s not terribly difficult to track how ditch weed evolved into sinsemilla. It is the historical result of several trends: 1) Selective breeding of cannabis strains with high THC/low CBD profiles, 2) near-universal preference for female plants (sinsemilla), 3) the rise of controlled-environment indoor cultivation, and 4) global availability of high-end hybrid seeds for commercial growing operations. And in the Australian sample, much of the marijuana came from areas like Byron Bay, Lismore, and Tweed Heads, where the concentration of specialist cultivators is similar to that of Humboldt County, California.

The investigators admit that “there is little research systematically addressing the public health impacts of use of different strengths and types of cannabis,” such as increases in cannabis addiction and mental health problems. The strongest evidence consistent with lab research is that “CBD may prevent or inhibit the psychotogenic and memory-impairing effects of THC. While the evidence for the ameliorating effects of CBD is not universal, it is thought that consumption of high THC/low CBD cannabis may predispose users towards adverse psychiatric effects….”

The THC rates in Australia are in line with or slightly higher than average values in several other countries. Can an increase in THC potency and corresponding reduction in other key cannabinoids be the reason for a concomitant increase in users seeking treatment for marijuana dependency? Not necessarily, say the investigators. Drug courts, coupled with greater treatment opportunities, might account for the rise. And schizophrenia? “Modelling research does not indicate increases in levels of schizophrenia commensurate with increases in cannabis use.”

One significant problem with surveys of this nature is the matter of determining marijuana’s effective potency—the amount of THC actually ingested by smokers. This may vary considerably, depending upon such factors as “natural variations in the cannabinoid content of plants, the part of the plant consumed, route of administration, and user titration of dose to compensate for differing levels of THC in different smoked material.”

Wendy Swift and her coworkers call for more research on cannabis users’ preferences, “which might shed light on whether cannabis containing a more balanced mix of THC and CBD would have value in the market, as well as potentially conferring reduced risks to mental wellbeing.”

Swift W., Wong A., Li K.M., Arnold J.C. & McGregor I.S. (2013). Analysis of Cannabis Seizures in NSW, Australia: Cannabis Potency and Cannabinoid Profile., PloS one, PMID: 23894589

(First published at Addiction Inbox Sept. 3 2013)

Graphics Credit: https://budgenius.com/marijuana-testing.html

Labels:

CBD,

legal marijuana,

marijuana,

marijuana health,

marijuana legalization,

THC,

THC levels

Thursday, February 5, 2015

Update on Synthetic Drug Surprises

Spicier than ever.

Four drug deaths last month in Britain have been blamed on so-called “Superman” pills being sold as Ecstasy, but actually containing PMMA, a synthetic stimulant drug with some MDMA-like effects that has been implicated in a number of deaths and hospitalizations in Europe and the U.S. The “fake Ecstasy” was also under suspicion in the September deaths of six people in Florida and another three in Chicago. An additional six deaths in Ireland have also been linked to the drug. (See Drugs.ie for more details.)

PMMA, or paramethoxymethamphetamine, causes dangerous increases in body temperature and blood pressure, is toxic at lower doses than Ecstasy, and requires up to two hours in order to take effect.

In other words, very nearly the perfect overdose drug.

Whether you call them “emerging drugs of misuse,” or “new psychoactive substances,” these synthetic highs have not gone away, and aren’t likely to. As Italian researchers have noted, “The web plays a major role in shaping this unregulated market, with users being attracted by these substances due to both their intense psychoactive effects and likely lack of detection in routine drug screenings.” Even more troubling is the fact that many of the novel compounds turning up as recreational drugs have been abandoned by legitimate chemists because of toxicity or addiction issues.

The Spice products—synthetic cannabinoids—are still the most common of the novel synthetic drugs. Hundreds of variants are now on the market. Science magazine recently reported on a UK study in which researchers discovered more than a dozen previously unknown psychoactive substances by conducting urine samples on portable toilets in Greater London. Call the mixture Spice, K2, Incense, Yucatan Fire, Black Mamba, or any other catchy, edgy name, and chances are, some kids will take it, both for the reported kick, and for the undetectability. According to NIDA, one out of nine U.S. 12th graders had used a synthetic cannabinoid product during the prior year.

“Laws just push forward the list of compounds,” Dr. Duccio Papanti, a psychiatrist at the University of Trieste who studies the new drugs, said in an interview for this article. “The market is very chaotic, bulk purchasing of pure compounds are cheaply available from China, India, Hong-Kong, but small labs are rising in Western Countries, too. Some authors point out that newer compounds are more related to harms (intoxications and deaths) than the older ones. You can clearly see from formulas that newer compounds are different from the first ones: new constituents are added, and there are structural changes, so although we have some clues about the metabolism of older, better studied compounds, we don't know anything about the newer (and currently used) ones."

The problems with synthetic cannabinoids often begin with headaches, vomiting, and hallucinations. At the Department of Medical, Surgical, and Health Sciences at the University of Trieste, researchers Samuele Naviglio, Duccio Papanti, Valentina Moressa, and Alessandro Ventura characterized the typical ER patient on synthetic cannabinoids, in a BMJ article: “On arrival at the emergency department he was conscious but drowsy and slow in answering simple questions. He reported frontal headache (8/10 on a visual analogue scale) and photophobia, and he was unable to stand unassisted. He was afebrile, his heart rate was 170 beats/min, and his blood pressure was 132/80 mm Hg.”

According to the BMJ paper, the most commonly reported adverse symptoms include: "Confusion, agitation, irritability, drowsiness, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis [sweating], mydriasis [excessive pupil dilation], and hallucinations. Other neurological and psychiatric effects include seizures, suicidal ideation, aggressive behavior, and psychosis. Ischemic stroke has also been reported. Gastrointestinal toxicity may cause xerostomia [dry mouth], nausea, and vomiting. Severe cardiotoxic effects have been described, including myocardial infarction…”

In a recent article (PDF) for World Psychiatry, Papanti and a group of other associates revealed additional features of synthetic cannabimemetics (SC), as they are officially known: “For example, inhibition of γ-aminobutyric acid receptors may cause anxiety, agitation, and seizures, whereas the activation of serotonin receptors and the inhibition of monoamine oxidases may be responsible for hallucinations and the occurrence of serotonin syndrome-like signs and symptoms.”

Papanti says researchers are also seeing more fluorinated drugs. “Fluorination is the incorporation of fluorine into a drug,” he says, one effect of which is “modulating the metabolism and increasing the lipophilicity, and enhancing absorption into biological membranes, including the blood-brain barrier, so that a drug is available at higher concentrations. An increasing number of fluorinated synthetic cannabinoids are available, and fluorinated cathinones are available, too.”

A primary problem is that physicians are still largely unacquainted with these chemicals, several years after their current popularity began. This is entirely understandable. In addition to the synthetic cathinones, several new mind-altering substances based on compounds discovered decades ago have also surfaced lately. Papanti provided a partial list of additional compounds that have led to official concern in the EU:

—Synthetic opioids (the best known are AH-7921, MT-45)

—Synthetic stimulants (the best known are MDPV, 4,4'-DMAR)

—New synthetic psychedelics (the NBOMe series)

—New dissociatives (Methoxetamine, Methoxphenidine, Diphenidine)

—New performance enhancing drugs (Melanotan, DNP)

—Gaba agonists (Phenibut, new benzodiazepines)

Most of the new and next-generation synthetics are not readily detected by standard drug screen processes. Spice drugs will not usually show up on anything but the most advanced test screening, using gas chromatography or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry—high tech tools which are rarely available for anything but serious (and costly) forensic investigations.

“Testing is a big problem,” Papanti declares. “From a clinical point of view, do you need the test to make a diagnosis of intoxication, for following up an addiction treatment, or for forensic purposes? With the new drugs, maybe taken together, with different pharmacology, we are not very sure about this yet. If I want to have confirmation of a diagnosis of SC intoxication, I need two weeks as an average, in order to obtain the result. Your patient has been discharged by that time, or in the worse case, he is dead.”

Another major problem, according to Papanti, “is that the machines need sample libraries in order to recognize the compound, and samples mean money. Plus, they need to be continuously updated.”

In summary, there is no antidote to these drugs, but intoxication is general less than 24 hours, and the indicated medical management is primarily supportive. If you plan to take a drug marketed as Ecstasy, or indeed any of the spice or bath salt compounds, Drugs.ie notes that there are some basic rules of conduct that will help maximize the odds of a safe trip:

—If you don’t “come up” as quickly as anticipated, don’t assume you need another pill. PMMA can take two hours or more to take effect. Do not “double drop.”

—If you don’t feel like you expected to feel, and are noticing a “pins-and-needles” feeling or numbness in the limbs, consider the possibility that another drug is involved.

—Don’t mix reputed Ecstasy with other drugs, especially alcohol, as PMMA reacts very dangerously with excessive alcohol.

—Remember to hydrate, but don’t overhydrate. If you go dancing, figure on about a pint per hour.

Wednesday, August 20, 2014

The Chemistry of Modern Marijuana

Is low-grade pot better for you than sinsemilla?

First published September 3, 2013.

Australia has one of the highest rates of marijuana use in the world, but until recently, nobody could say for certain what, exactly, Australians were smoking. Researchers at the University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales analyzed hundreds of cannabis samples seized by Australian police, and put together comprehensive data on street-level marijuana potency across the country. They sampled police seizures and plants from crop eradication operations. The mean THC content of the samples was 14.88%, while absolute levels varied from less than 1% THC to almost 40%. Writing in PLoS ONE, Wendy Swift and colleagues found that roughly ¾ of the samples contained at least 10% total THC. Half the samples contained levels of 15% or higher—“the level recommended by the Garretsen Commission as warranting classification of cannabis as a ‘hard’ drug in the Netherlands.”

In the U.S., recent studies have shown that THC levels in cannabis from 1993 averaged 3.4%, and then soared to THC levels in 2008 of almost 9%. THC loads more than doubled in 15 years, but that is still a far cry from news reports erroneously referring to organic THC increases of 10 times or more.

CBD, or cannabidiol, another constituent of cannabis, has garnered considerable attention in the research community as well as the medical marijuana constituency due to its anti-emetic properties. Like many other cannabinoids, CBD is non-psychoactive, and acts as a muscle relaxant as well. CBD levels in the U.S. have remained consistently low over the past 20 years, at 0.3-0.4%. In the Australian study, about 90% of cannabis samples contained less than 0.1% total CBD, based on chromatographic analysis, although some of the samples had levels as high as 6%.

The Australian samples also showed relatively high amounts of CBG, another common cannabinoid. CBG, known as cannabigerol, has been investigated for its pharmacological properties by biotech labs. It is non-psychoactive but useful for inducing sleep and lowering intra-ocular pressure in cases of glaucoma.

CBC, yet another cannabinoid, also acts as a sedative, and is reported to relieve pain, while also moderating the effects of THC. The Australian investigators believe that, as with CBD, “the trend for maximizing THC production may have led to marginalization of CBC as historically, CBC has sometimes been reported to be the second or third most abundant cannabinoid.”

Is today’s potent, very high-THC marijuana a different drug entirely, compared to the marijuana consumed up until the 21st Century? And does super-grass have an adverse effect on the mental health of users? The most obvious answer is, probably not. Recent attempts to link strong pot to the emergence of psychosis have not been definitive, or even terribly convincing. (However, the evidence for adverse cognitive effects in smokers who start young is more convincing).

It’s not terribly difficult to track how ordinary marijuana evolved into sinsemilla. Think Luther Burbank and global chemistry geeks. It is the historical result of several trends: 1) Selective breeding of cannabis strains with high THC/low CBD profiles, 2) near-universal preference for female plants (sinsemilla), 3) the rise of controlled-environment indoor cultivation, and 4) global availability of high-end hybrid seeds for commercial growing operations. And in the Australian sample, much of the marijuana came from areas like Byron Bay, Lismore, and Tweed Heads, where the concentration of specialist cultivators is similar to that of Humboldt County, California.

The investigators admit that “there is little research systematically addressing the public health impacts of use of different strengths and types of cannabis,” such as increases in cannabis addiction and mental health problems. The strongest evidence consistent with lab research is that “CBD may prevent or inhibit the psychotogenic and memory-impairing effects of THC. While the evidence for the ameliorating effects of CBD is not universal, it is thought that consumption of high THC/low CBD cannabis may predispose users towards adverse psychiatric effects….”

The THC rates in Australia are in line with or slightly higher than average values in several other countries. Can an increase in THC potency and corresponding reduction in other key cannabinoids be the reason for a concomitant increase in users seeking treatment for marijuana dependency? Not necessarily, say the investigators. Drug courts, coupled with greater treatment opportunities, might account for the rise. And schizophrenia? “Modelling research does not indicate increases in levels of schizophrenia commensurate with increases in cannabis use.”

One significant problem with surveys of this nature is the matter of determining marijuana’s effective potency—the amount of THC actually ingested by smokers. This may vary considerably, depending upon such factors as “natural variations in the cannabinoid content of plants, the part of the plant consumed, route of administration, and user titration of dose to compensate for differing levels of THC in different smoked material.”

Wendy Swift and her coworkers call for more research on cannabis users’ preferences, “which might shed light on whether cannabis containing a more balanced mix of THC and CBD would have value in the market, as well as potentially conferring reduced risks to mental wellbeing.”

Graphics Credit: http://www.ironlabsllc.co/view/learn.php

Swift W., Wong A., Li K.M., Arnold J.C. & McGregor I.S. (2013). Analysis of Cannabis Seizures in NSW, Australia: Cannabis Potency and Cannabinoid Profile., PloS one, PMID: 23894589

Labels:

cannabis,

CBD,

marijuana,

marijuana chemistry,

marijuana laws,

strong weed,

THC,

THC levels

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Avoid the ‘Noid: Synthetic Cannabinoids and “Spiceophrenia”

Like PCP all over again.

Synthetic cannabis-like “Spice” drugs were first introduced in early 2004, and quickly created a global marketplace. But the drugs responsible for the psychoactive effects of Spice products weren’t widely characterized until late 2008. And only recently have researchers made significant progress toward understanding why these drugs cause so many problems, compared to organic marijuana.

Synthetic cannabinoids (SC), as a class of drugs, are generally more potent at cannabinoid receptors than marijuana itself. As full agonists, synthetic cannabinoids show binding affinities between 5 and 10,000 times higher than THC at these receptors.

A recent literature study by Duccio Papanti at the University of Trieste and coworkers sheds additional light on the problematic nature of these drugs. In an article for Advances in Dual Diagnosis titled “’Noids in a nutshell: everything you (don’t) want to know about synthetic cannabimimetics,” the researchers note that “Spice products’ effects have been anecdotally described by users as intense and ‘trippy’ marijuana-like, with hallucinatory experiences being associated with higher levels of intake. In comparison with cannabis, SC compounds may be associated with quicker ‘kick off’ effects; significantly shorter duration of action; larger levels of hangover effects; and more frequent paranoid feelings.”

The study also points out a trouble spot: “Super-concentrations of synthetic cannabinoids (e.g. ‘hot-spots’) in herbal blends, originating from a non-optimal homogenization between synthetic cannabinoids and the vegetal substrate, can result in overdoses/intoxications and ‘bad trips’ in users.” In other words, the chemical powder is often so poorly mixed with the vegetable matter that potencies in the batch can be way too high, depending upon the luck of the draw, and are bound to vary from batch to batch in any event.

Nonetheless, there is a cluster of specific health effects that brings users to the emergency room. The typical set of symptoms—bearing in mind that polydrug use always complicates the picture—include elevated heart rate, elevated blood pressure, visual and auditory hallucinations, agitation, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, and seizures.

The authors note that “nausea and seizures are very uncommon in marijuana use, due to the suggested anticonvulsant/antiemetic properties of cannabis.” In fact, misusers who present doctors with vomiting as a symptom are often assumed to be free of cannabis-type drugs. Not so with synthetic cannabinoids. In an email interview, lead author Duccio Papanti told me that “many users describe the occurrence of vomiting, even with a non-recurrent and low use of these compounds. My idea is that this may be due to the smoking of hot-spotted blends, and that at high concentrations these compounds can work more on 5-HT receptors (in fact, vomit and seizures are signs of a serotonin syndrome).”

Less common, luckily, are other medical issues like heart attack, kidney injuries, and stroke. Of primary concern, the authors warn, are the reported incidents of “transient psychotic episodes,” “relapse of a primary psychosis,” and “‘ex novo’ psychosis in previous psychosis-free subjects.”

As for the mechanism behind the reported hallucinogenic effects: “A number of synthetic cannabinoids contain an indole moiety, either in their basic structure or in their substituents.” Indoles are molecular groups structurally similar to serotonin, and are active in drugs like LSD and DMT.

“According to this finding,” Papanti says, “their use could interfere with serotonin 5-HT neurotransmission more than THC. It is possible that the indole moieties incorporated in the molecules of synthetic cannabinoids can bind 5-HT2 receptors, acting as an hallucinogenic drug (in fact visual hallucinations are not uncommon in SC use).”

One of the main problems, of course, is that physicians know almost nothing about detecting and treating acute overdoses of synthetic cannabinoid products. And even if an OD victim was lucky enough to wash up at a health facility that had access to instant chromatography detection testing, “[due to] the lack of appropriate reference samples, SC compounds are difficult to identify.”

The risk here is not evenly distributed, obviously. Young people, and anybody subject to marijuana urine testing, are the clear market for these products. This includes students, athletes, members of the Armed Forces, transportation workers, mining workers, and many others. Spice users are overwhelmingly male.

How many people are taking the risk? An estimate of student use comes from the U.S. 2013 “Monitoring the Future” survey, which shows that about 8% of 17-18 year-olds have tried Spice products. For 12th graders, Spice products are second only to marijuana itself in many districts. And yet there is a dearth of longitudinal studies in humans to evaluate the long-term impact of using synthetic cannabinoids.

Papanti and colleagues call for the creation of an international agency dedicated to “toxicovigilance” based on a “non-biased ‘real-time’ database,” including adverse drug effects, as a way of clarifying and promoting appropriate clinical guidelines for Spice drugs. “These substances are dangerous, and they have been associated with a number of deaths,” Papanti says. He would like to see a “network in which users report their adverse effects. Such an online system already exists in the Pharmacovigilance program at the Lareb Centre in the Netherlands. They collect reports of medications’ adverse effects from both patients and doctors and it works very well.”

Tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal have all been documented in several categories of Spice products. Spice withdrawal effects can be severe, the authors say, and may include craving, tremor, profuse sweating, insomnia, anxiety, irritability and depression.

Graphics Credit: http://www.caregroupnz.org.nz/drug-prevention-education-campaign/

Saturday, July 26, 2014

Getting Spiced

I wish I could stop writing blog posts about Spice, as the family of synthetic cannabinoids has become known. I wish young people would stop taking these drugs, and stick to genuine marijuana, which is far safer. I wish that politicians and proponents of the Drug War would lean in a bit and help, by knocking off the testing for marijuana in most circumstances, so the difficulty of detecting Spice products isn’t a significant factor in their favor. I wish synthetic cannabinoids weren’t research chemicals, untested for safety in humans, so that I could avoid having to sound like an alarmist geek on the topic. I wish I didn’t have to discuss the clinical toxicity of more powerful synthetic cannabinoids like JWH-122 and JWH-210. I wish talented chemists didn’t have to spend precious time and lab resources laboriously characterizing the various metabolic pathways of these drugs, in an effort to understand their clinical consequences. I wish Spice drugs didn’t make regular cannabis look so good by comparison, and serve as an argument in favor of more widespread legalization of organic marijuana.

A German study, published in Addiction, seems to demonstrate that “from 2008 to 2011 a shift to the extremely potent synthetic cannabinoids JWH-122 and JWH-210 occurred…. Symptoms were mostly similar to adverse effects after high-dose cannabis. However, agitation, seizures, hypertension, emesis, and hypokalemia [low blood potassium] also occurred—symptoms which are usually not seen even after high doses of cannabis.”

The German patients in the study were located through the Poison Information Center, and toxicological analysis was performed in the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University Medical Center Freiburg. Only two study subjects had appreciable levels of actual THC in their blood. Alcohol and other confounders were factored out. First-time consumers were at elevated risk for unintended overdose consequences, since tolerance to Spice drug side effects does develop, as it does with marijuana.

Clinically, the common symptom was tachycardia, with hearts rates as high as 170 beats per minute. Blurred vision, hallucinations and agitation were also reported, but this cluster of symptoms is also seen in high-dose THC cases that turn up in emergency rooms. The same with nausea, the most common gastrointestinal complaint logged by the researchers.

But in 29 patients in whom the presence of synthetic cannabinoids was verified, some of the symptoms seem unique to the Spice drugs. The synthetic cannabinoids caused, in at least one case, an epileptic seizure. Hypertension and low potassium were also seen more often with the synthetics. After the introduction of the more potent forms, JWH-122 and JWH-210, the symptom set expanded to include “generalized seizures, myocloni [muscle spasms] and muscle pain, elevation of creatine kinase and hypokalemia.” The researchers note that seizures induced by marijuana are almost unheard of. In fact, studies have shown that marijuana has anticonvulsive properties, one of the reason it is popular with cancer patients being treated with radiation therapy.

And there are literally hundreds of other synthetic cannabinoid chemicals waiting in the wings. What is going on? Two things. First, synthetic cannabinoids, unlike THC itself, are full agonists at CB1 receptors. THC is only a partial agonist. What this means is that, because of the greater affinity for cannabinoid receptors, synthetic cannabinoids are, in general, stronger than marijuana—strong enough, in fact, to be toxic, possibly even lethal. Secondly, CB1 receptors are everywhere in the brain and body. The human cannabinoid type-1 receptor is one of the most abundant receptors in the central nervous system and is found in particularly high density in brain areas involving cognition and memory.

The Addiction paper by Maren Hermanns-Clausen and colleagues at the Freiburg University Medical Center in Germany is titled “Acute toxicity due to the confirmed consumption of synthetic cannabinoids,” and is worth quoting at some length:

The central nervous excitation with the symptoms agitation, panic attack, aggressiveness and seizure in our case series is remarkable, and may be typical for these novel synthetic cannabinoids. It is somewhat unlikely that co-consumption of amphetamine-like drugs was responsible for the excitation, because such co-consumption occurred in only two of our cases. The appearance of myocloni and generalized tonic-clonic seizures is worrying. These effects are also unexpected because phytocannabinoids [marijuana] show anticonvulsive actions in humans and in animal models of epilepsy.

The reason for all this may be related to the fact that low potassium was observed “in about one-third of the patients of our case series.” Low potassium levels in the blood can cause muscle spasms, abnormal heart rhythms, and other unpleasant side effects.

One happier possibility that arises from the research is that the fierce affinity of synthetic cannabinoids for CB1 receptors could be used against them. “A selective CB1 receptor antagonist,” Hermanns-Clausen and colleagues write, “for example rimonabant, would immediately reverse the acute toxic effects of the synthetic cannabinoids.”

The total number of cases in the study was low, and we can’t assume that everyone who smokes a Spice joint will suffer from epileptic seizures. But we can say that synthetic cannabinoids in the recreational drug market are becoming stronger, are appearing in ever more baffling combinations, and have made the matter of not taking too much a central issue, unlike marijuana, where taking too much leads to nausea, overeating, and sleep.

(See my post “Spiceophrenia” for a discussion of the less-compelling evidence for synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis).

Hermanns-Clausen M., Kneisel S., Hutter M., Szabo B. & Auwärter V. (2013). Acute intoxication by synthetic cannabinoids - Four case reports, Drug Testing and Analysis, n/a-n/a. DOI: 10.1002/dta.1483

Graphics Credit: http://www.aacc.org/

Monday, July 21, 2014

Hunting For the Marijuana-Dopamine Connection

Most drugs of abuse increase dopamine transmission in the brain, and indeed, this is thought to be the basic neural mechanism underlying the rewarding effects of addictive drugs. But in the case of marijuana, the dopamine connection is not so clear-cut. Evidence has been found both for and against the notion of increases in dopamine signaling during marijuana intoxication.

Marijuana has always been the odd duck in the pond, research-wise. Partly this is due to longstanding federal intransigence toward cannabis research, and partly it is because cannabis, chemically speaking, is damnably complicated. The question of marijuana’s effect on dopamine transmission came under strong scrutiny a few years ago, when UK researchers began beating the drums for a theory that chronic consumption of strong cannabis can not only trigger episodes of psychosis, but can be viewed as the actual cause of schizophrenia in some cases.

It sounded like a new version of the old reefer madness, but this time around, the researchers raising their eyebrows had a new fact at hand: Modern marijuana is several times stronger than marijuana in use decades ago. Selective breeding for high THC content has produced some truly formidable strains of pot, even if cooler heads have slowly prevailed on the schizophrenia issue.

One of the reports helping to bank the fires on this notion appeared recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Joanna S. Fowler of the Biosciences Department at Brookhaven National Laboratory, Director Nora Volkow of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and other researchers compared brain dopamine reactivity in healthy controls and heavy marijuana users, using PET scans. For measuring dopamine reactivity, the researchers chose methylphenidate, better known as Ritalin, the psychostimulant frequently prescribed for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ritalin basically functions as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor, meaning that the use of Ritalin leads to increased concentrations of synaptic dopamine.

In the study, heavy marijuana users showed a blunted reaction to the stimulant Ritalin due to reductions in brain dopamine release, according to the research. “The potency of methylphenidate (MP) was also reported to be stronger by the controls than by the marijuana abusers." And in marijuana abusers, Ritalin caused an increase in craving for marijuana and cigarettes.

“We found that marijuana abusers display attenuated dopamine responses to MP including reduced decreases in striatal distribution volumes,” according to the study’s conclusion. “The significantly attenuated behavioral and striatal distribution volumes response to MP in marijuana abusers compared to controls, indicates reduced brain reactivity to dopamine stimulation that in the ventral striatum might contribute to negative emotionality and drug craving.”

Down-regulation from extended abuse is another complicated aspect of this: “Although, to our knowledge, this is the first clinical report of an attenuation of the effects of MP in marijuana abusers, a preclinical study had reported that rats treated chronically with THC exhibited attenuated locomotor responses to amphetamine. Such blunted responses to MP could reflect neuroadaptations from repeated marijuana abuse, such as downregulation of DA transporters.”

Animal studies have suggested that these dopamine alterations are reversible over time.

Another recent study came to essentially the same conclusions. Writing in Biological Psychiatry, a group of British researchers led by Michael A.P. Bloomfield and Oliver D. Howes analyzed dope smokers who experienced psychotic symptoms when they were intoxicated. They looked for evidence of a link between cannabis use and psychosis and concluded: “These findings indicate that chronic cannabis use is associated with reduced dopamine synthesis capacity and question the hypothesis that cannabis increases the risk of psychotic disorders by inducing the same dopaminergic alterations seen in schizophrenia.” And again, the higher the level of current cannabis use, the lower the level of striatal dopamine synthesis capacity. As for mechanisms, the investigators ran up against similar causation problems: “One explanation for our findings is that chronic cannabis use is associated with dopaminergic down-regulation. This might underlie amotivation and reduced reward sensitivity in chronic cannabis users. Alternatively, preclinical evidence suggests that low dopamine neurotransmission may predispose an individual to substance use.”

The findings of diminished responses to Ritalin in heavy marijuana users may have clinical implications, suggesting that marijuana abusers with ADHD may experience reduced benefits from stimulant medications.

Photo Credit: http://www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/

Monday, October 7, 2013

Spiced: Synthetic Cannabis Keeps Getting Stronger

Case reports of seizures in Germany from 2008 to 2011.

I wish I could stop writing blog posts about Spice, as the family of synthetic cannabinoids has become known. I wish young people would stop taking these drugs, and stick to genuine marijuana, which is far safer. I wish that politicians and proponents of the Drug War would lean in a bit and help, by knocking off the testing for marijuana in most circumstances, so the difficulty of detecting Spice products isn’t a significant factor in their favor. I wish synthetic cannabinoids weren’t research chemicals, untested for safety in humans, so that I could avoid having to sound like an alarmist geek on the topic. I wish I didn’t have to discuss the clinical toxicity of more powerful synthetic cannabinoids like JWH-122 and JWH-210. I wish talented chemists didn’t have to spend precious time and lab resources laboriously characterizing the various metabolic pathways of these drugs, in an effort to understand their clinical consequences. I wish Spice drugs didn’t make regular cannabis look so good by comparison, and serve as an argument in favor of more widespread legalization of organic marijuana.

A German study, published in Addiction, seems to demonstrate that “from 2008 to 2011 a shift to the extremely potent synthetic cannabinoids JWH-122 and JWH-210 occurred…. Symptoms were mostly similar to adverse effects after high-dose cannabis. However, agitation, seizures, hypertension, emesis, and hypokalemia [low blood potassium] also occurred—symptoms which are usually not seen even after high doses of cannabis.”

The German patients in the study were located through the Poison Information Center, and toxicological analysis was performed in the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University Medical Center Freiburg. Only two study subjects had appreciable levels of actual THC in their blood. Alcohol and other confounders were factored out. First-time consumers were at elevated risk for unintended overdose consequences, since tolerance to Spice drug side effects does develop, as it does with marijuana.

Clinically, the common symptom was tachycardia, with hearts rates as high as 170 beats per minute. Blurred vision, hallucinations and agitation were also reported, but this cluster of symptoms is also seen in high-dose THC cases that turn up in emergency rooms. The same with nausea, the most common gastrointestinal complaint logged by the researchers.

But in 29 patients in whom the presence of synthetic cannabinoids was verified, some of the symptoms seem unique to the Spice drugs. The synthetic cannabinoids caused, in at least one case, an epileptic seizure. Hypertension and low potassium were also seen more often with the synthetics. After the introduction of the more potent forms, JWH-122 and JWH-210, the symptom set expanded to include “generalized seizures, myocloni [muscle spasms] and muscle pain, elevation of creatine kinase and hypokalemia.” The researchers note that seizures induced by marijuana are almost unheard of. In fact, studies have shown that marijuana has anticonvulsive properties, one of the reason it is popular with cancer patients being treated with radiation therapy.

And there are literally hundreds of other synthetic cannabinoid chemicals waiting in the wings. What is going on? Two things. First, synthetic cannabinoids, unlike THC itself, are full agonists at CB1 receptors. THC is only a partial agonist. What this means is that, because of the greater affinity for cannabinoid receptors, synthetic cannabinoids are, in general, stronger than marijuana—strong enough, in fact, to be toxic, possibly even lethal. Secondly, CB1 receptors are everywhere in the brain and body. The human cannabinoid type-1 receptor is one of the most abundant receptors in the central nervous system and is found in particularly high density in brain areas involving cognition and memory.

The Addiction paper by Maren Hermanns-Clausen and colleagues at the Freiburg University Medical Center in Germany is titled “Acute toxicity due to the confirmed consumption of synthetic cannabinoids,” and is worth quoting at some length:

The central nervous excitation with the symptoms agitation, panic attack, aggressiveness and seizure in our case series is remarkable, and may be typical for these novel synthetic cannabinoids. It is somewhat unlikely that co-consumption of amphetamine-like drugs was responsible for the excitation, because such co-consumption occurred in only two of our cases. The appearance of myocloni and generalized tonic-clonic seizures is worrying. These effects are also unexpected because phytocannabinoids [marijuana] show anticonvulsive actions in humans and in animal models of epilepsy.

The reason for all this may be related to the fact that low potassium was observed “in about one-third of the patients of our case series.” Low potassium levels in the blood can cause muscle spasms, abnormal heart rhythms, and other unpleasant side effects.

One happier possibility that arises from the research is that the fierce affinity of synthetic cannabinoids for CB1 receptors could be used against them. “A selective CB1 receptor antagonist,” Hermanns-Clausen and colleagues write, “for example rimonabant, would immediately reverse the acute toxic effects of the synthetic cannabinoids.”

The total number of cases in the study was low, and we can’t assume that everyone who smokes a Spice joint will suffer from epileptic seizures. But we can say that synthetic cannabinoids in the recreational drug market are becoming stronger, are appearing in ever more baffling combinations, and have made the matter of not taking too much a central issue, unlike marijuana, where taking too much leads to nausea, overeating, and sleep.

(See my post “Spiceophrenia” for a discussion of the less-compelling evidence for synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis).

Hermanns-Clausen M., Kneisel S., Hutter M., Szabo B. & Auwärter V. (2013). Acute intoxication by synthetic cannabinoids - Four case reports, Drug Testing and Analysis, n/a-n/a. DOI: 10.1002/dta.1483

Graphics Credit: http://www.aacc.org/

Tuesday, September 3, 2013

A Chemical Peek at Modern Marijuana

Researchers ponder whether ditch weed is better for you than sinsemilla.

Australia has one of the highest rates of marijuana use in the world, but until recently, nobody could say for certain what, exactly, Australians were smoking. Researchers at the University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales recently analyzed hundreds of cannabis samples seized by Australian police, and put together comprehensive data on street-level marijuana potency across the country. They sampled police seizures and plants from crop eradication operations. The mean THC content of the samples was 14.88%, while absolute levels varied from less than 1% THC to almost 40%. Writing in PLoS one, Wendy Swift and colleagues found that roughly ¾ of the samples contained at least 10% total THC. Half the samples contained levels of 15% or higher—“the level recommended by the Garretsen Commission as warranting classification of cannabis as a ‘hard’ drug in the Netherlands.”

In the U.S., recent studies have shown that THC levels in cannabis from 1993 averaged 3.4%, and then soared to THC levels in 2008 of almost 9%. THC loads more than doubled in 15 years, but that is still a far cry from news reports erroneously referring to organic THC increases of 10 times or more.

CBD, or cannabidiol, another constituent of cannabis, has garnered considerable attention in the research community as well as the medical marijuana constituency due to its anti-emetic properties. Like many other cannabinoids, CBD is non-psychoactive, and acts as a muscle relaxant as well. CBD levels in the U.S. have remained consistently low over the past 20 years, at 0.3-0.4%. In the Australian study, about 90% of cannabis samples contained less than 0.1% total CBD, based on chromatographic analysis, although some of the samples had levels as high as 6%.

The Australian samples also showed relatively high amounts of CBG, another common cannabinoid. CBG, known as cannabigerol, has been investigated for its pharmacological properties by biotech labs. It is non-psychoactive but useful for inducing sleep and lowering intra-ocular pressure in cases of glaucoma.

CBC, yet another cannabinoid, also acts as a sedative, and is reported to relieve pain, while also moderating the effects of THC. The Australian investigators believe that, as with CBD, “the trend for maximizing THC production may have led to marginalization of CBC as historically, CBC has sometimes been reported to be the second or third most abundant cannabinoid.”

Is today’s potent, very high-THC marijuana a different drug entirely, compared to the marijuana consumed up until the 21st Century? And does super-grass have an adverse effect on the mental health of users? The most obvious answer is, probably not. Recent attempts to link strong pot to the emergence of psychosis have not been definitive, or even terribly convincing. (However, the evidence for adverse cognitive effects in smokers who start young is more convincing).

It’s not terribly difficult to track how ditch weed evolved into sinsemilla. It is the historical result of several trends: 1) Selective breeding of cannabis strains with high THC/low CBD profiles, 2) near-universal preference for female plants (sinsemilla), 3) the rise of controlled-environment indoor cultivation, and 4) global availability of high-end hybrid seeds for commercial growing operations. And in the Australian sample, much of the marijuana came from areas like Byron Bay, Lismore, and Tweed Heads, where the concentration of specialist cultivators is similar to that of Humboldt County, California.

The investigators admit that “there is little research systematically addressing the public health impacts of use of different strengths and types of cannabis,” such as increases in cannabis addiction and mental health problems. The strongest evidence consistent with lab research is that “CBD may prevent or inhibit the psychotogenic and memory-impairing effects of THC. While the evidence for the ameliorating effects of CBD is not universal, it is thought that consumption of high THC/low CBD cannabis may predispose users towards adverse psychiatric effects….”

The THC rates in Australia are in line with or slightly higher than average values in several other countries. Can an increase in THC potency and corresponding reduction in other key cannabinoids be the reason for a concomitant increase in users seeking treatment for marijuana dependency? Not necessarily, say the investigators. Drug courts, coupled with greater treatment opportunities, might account for the rise. And schizophrenia? “Modelling research does not indicate increases in levels of schizophrenia commensurate with increases in cannabis use.”

One significant problem with surveys of this nature is the matter of determining marijuana’s effective potency—the amount of THC actually ingested by smokers. This may vary considerably, depending upon such factors as “natural variations in the cannabinoid content of plants, the part of the plant consumed, route of administration, and user titration of dose to compensate for differing levels of THC in different smoked material.”

Wendy Swift and her coworkers call for more research on cannabis users’ preferences, “which might shed light on whether cannabis containing a more balanced mix of THC and CBD would have value in the market, as well as potentially conferring reduced risks to mental wellbeing.”

Swift W., Wong A., Li K.M., Arnold J.C. & McGregor I.S. (2013). Analysis of Cannabis Seizures in NSW, Australia: Cannabis Potency and Cannabinoid Profile., PloS one, PMID: 23894589

Graphics Credit: http://420tribune.com

Thursday, August 22, 2013

“Spiceophrenia”

Synthetic cannabimimetics and psychosis.

Not long ago, public health officials were obsessing over the possibility that “skunk” marijuana—loosely defined as marijuana exhibiting THC concentrations above 12%, and little or no cannabidiol (CBD), the second crucial ingredient in marijuana—caused psychosis. In some cases, strong pot was blamed for the onset of schizophrenia.

The evidence was never very solid for that contention, but now the same questions have arisen with respect to synthetic cannabimimetics—drugs that have THC-like effects, but no THC. They are sold as spice, incense, K2, Aroma, Krypton, Bonzai, and dozens of other product monikers, and have been called “probationer’s weed” for their ability to elude standard marijuana drug testing. Now a group of researchers drawn primarily from the University of Trieste Medical School in Italy analyzed a total of 223 relevant studies, and boiled them down to the 41 best investigations for systematic review, to see what evidence exists for connecting spice drugs with clinical psychoses.

Average age of users was 23, and the most common compounds identified using biological specimen analysis were the now-familiar Huffman compounds, based on work at Clemson University by John W. Huffman, professor emeritus of organic chemistry: JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-122, JWH-250. (The investigators also found CP-47,497, a cannabinoid receptor agonist developed in the 80s by Pfizer and used in scientific research.) The JWH family consists of very powerful drugs that are full agonists at CB-1 and CB-2 receptors, where, according to the study, “they are more powerful than THC itself.” What prompted the investigation was the continued arrival of users in hospitals and emergency rooms, presenting with symptoms of agitation, anxiety, panic, confusion, combativeness, paranoia, and suicidal ideation. Physical effects can includes elevated blood pressure and heart rate, nausea, hallucinations, and seizures.

One of the many problems for researchers and health officials is the lack of a widely available set of reference samples for precise identification of the welter of cannabis-like drugs now available. In addition, the synthetic cannabimimetics (SCs) are frequently mixed together, or mixed with other psychoactive compounds, making identification even more difficult. Add in the presence of masking agents, along with various herbal substances, and it becomes very difficult to find out which of the new drugs—none of which were intended for human use—are bad bets.

Availing themselves of toxicology tests, lab studies, and various surveys, the researchers, writing in Human Psychopharmacology’s Special Issue on Novel Psychoactive Substances, crunched the data related to a range of psychopathological issues reported with SCs—and the results were less than definitive. They found that many of the psychotic symptoms occurred in people who had been previously diagnosed with an existing form of mental disturbance, such as depression, ADHD, or PTSD. But they were able to determine that psychopathological syndromes were far less common with marijuana than with SCs. And those who experienced psychotic episodes on Spice-type drugs presented with “higher/more frequent levels of agitation and behavioral dyscontrol in comparison with those psychotic episodes described in marijuana misusers.”

In the end, the researchers can do no better than to conclude that “the exact risk of developing a psychosis following SC misuse cannot be calculated.” What would the researchers need to demonstrate solid causality between designer cannabis products and psychosis? More product consistency, for one thing, because “the polysubstance intake pattern typically described in SC misusers may act as a significant confounder” when it comes to developing toxicological screening tools. Perhaps most disheartening is “the large structural heterogeneity between the different SC compounds,” which limited the researchers’ ability to interpret the data.

This stuff matters, because the use of Spice-type drugs is reported to be increasing in the U.S. and Europe. Online suppliers are proliferating as well. And the drugs are particularly popular with teens and young adults. Young people are more likely to be drug-naïve or have limited exposure to strong drugs, and there is some evidence that children and adolescents are adversely affected by major exposure to drugs that interact with cannabinoid receptors in the brain.

Graphics credit: http://scientopia.org/blogs/drugmonkey/

Monday, August 13, 2012

Synthetic Drugs: Collected Posts

Catching up with bath salts and spice.

The Low Down on the New Highs: Not all bath salts are alike.

“You’re 16 hours into your 24-hour shift on the medic unit, and you find yourself responding to an “unknown problem” call.... Walking up to the patient, you note a slender male sitting wide-eyed on the sidewalk. His skin is noticeably flushed and diaphoretic, and he appears extremely tense. You notice slight tremors in his upper body, a clenched jaw and a vacant look in his eyes.... As you begin to apply the blood pressure cuff, the patient begins violently resisting and thrashing about on the sidewalk—still handcuffed. Nothing seems to calm him, and he simultaneously bangs his head on the sidewalk and tries to kick you...” [Go here]

The New Highs: Are Bath Salts Addictive? What we know and don’t know about synthetic speed.

Call bath salts a new trend, if you insist. Do they cause psychosis? Are they “super-LSD?” The truth is, they are a continuation of a 70-year old trend: speed. Lately, we’ve been fretting about the Adderall Generation, but every population cohort has had its own confrontation with the pleasures and perils of speed: Ritalin, ice, Methedrine, crystal meth, IV meth, amphetamine, Dexedrine, Benzedrine… and so it goes. For addicts: Speed kills. Those two words were found all over posters in the Haight Ashbury district of San Francisco, a few years too late to do the residents much good…. [Go here]

“Bath Salts” and Ecstasy Implicated in Kidney Injuries: “A potentially life-threatening situation.”

Earlier this month, state officials became alarmed by a cluster of puzzling health problems that had suddenly popped up in Casper, Wyoming, population 55,000. Three young people had been hospitalized with kidney injuries, and dozens of others were allegedly suffering from vomiting and back pain after smoking or snorting an herbal product sold as “blueberry spice.” The Poison Review reported that the outbreak was presently under investigation by state medical officials. “At this point we are viewing use of this drug as a potentially life-threatening situation,” said Tracy Murphy, Wyoming state epidemiologist…. [Go here]

The Triumph of Synthetics: Designer stimulants surpass heroin and cocaine.

A troubling report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) shows that amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) have, for the first time, become more popular around the world than heroin and cocaine. Marijuana remains the most popular illegal drug in the world, and the use of amphetamines has fallen sharply in the U.S., but the world trend represents the worldwide triumph of synthetic drug design over the plant-based “hard drugs” of the past…. [Go here]

Marijuana: The New Generation: What’s in that “Spice” packet?

They first turned up in Europe and the U.K.; those neon-colored foil packets labeled “Spice,” sold in small stores and novelty shops, next to the 2 oz. power drinks and the caffeine pills. Unlike the stimulants known as mephedrone or M-Cat, or the several variations on the formula for MDMA—both of which have also been marketed as Spice and “bath salts”—the bulk of the new products in the Spice line were synthetic versions of cannabis…. [Go here]

An Interview with Pharmacologist David Kroll: On synthetic marijuana, organic medicines, and drugs of the future.

Herewith, a 5-question interview with pharmacologist David Kroll, Ph.D., Professor and Chair of Pharmaceutical Science at North Carolina Central University in Durham, and a well-known blogger in the online science community. A cancer pharmacologist whose field is natural products—he’s currently involved in a project to explore the potential anticancer action of chemicals found in milk thistle and various sorts of fungi—Dr. Kroll received his Ph.D. from the University of Florida, and completed his postdoctoral fellowship in Medical Oncology and Molecular Endocrinology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He went on to spend the first nine years of his independent research and teaching career at the University of Colorado School of Pharmacy, where he taught all aspects of pharmacology, from central nervous system-active drugs, to anticancer and antiviral medications…. [Go here]

Mephedrone, the New Drug in Town: Bull market for quasi-legal designer highs.

Most people in the United States have never heard of it. Very few have ever tried it. But if Europe is any kind of leading indicator for synthetic drugs (and it is), then America will shortly have a chance to get acquainted with mephedrone, a.k.a. Drone, MCAT, 4-methylmethcathinone (4-MMC), and Meow Meow--the latter nickname presumably in honor of its membership in the cathinone family, making it chemically similar in some ways to amphetamine and ephedrine. But its users often refer to effects more commonly associated with Ecstasy (MDMA), both the good (euphoria, empathy, talkativeness) and the bad (blood pressure spikes, delusions, drastic changes in body temperature)…. [Go here]

Tracking Synthetic Highs: UN office monitors designer drug trade.

Produced by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the Global SMART Update (PDF) for October provides interim reports of emerging trends in synthetic drug use. The report does not concern itself with cocaine, heroin, marijuana, alcohol, or tobacco. “Unlike plant-based drugs,” says the report, “synthetic drugs are quickly evolving with new designer drugs appearing on the market each year.” The update deals primarily with amphetamine-type stimulants, but also includes newer designer drugs such as mephedrone, atypical synthetics like ketamine, synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and old standbys like LSD…. [Go here]

The New Cannabinoids: Army fears influx of synthetic marijuana.

It’s a common rumor: Spice, as the new synthetic cannabis-like products are usually called, will get you high--but will allow you to pass a drug urinalysis. And for this reason, rumor has it, Spice is becoming very popular in exactly the places it might be least welcomed: Police stations, fire departments—and army bases. What the hell is this stuff? [Go here]

Photo credit: http://gizmodo.com/

photo credit 2: http://www.clemson.edu/

Monday, July 2, 2012

Screen Time is Melting Our Children’s Brains—Or Something

An ad hoc symposium.

Earlier this week, a post at Psychology Today—“Computer, Video Games and Psychosis: Cause for Concern"—by child psychiatrist Victoria-Dunckley stirred up a bit of social media traffic with her contention that an excess exposure to video screens is responsible for the spread of hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms in our nation’s young. She is not calling this behavior an addiction as such, but maintains that it only happens in cases where 15-22-year olds, were “plugged in” for six or more hours each day.

Her theory: “Electronic screens, particularly interactive ones (as opposed to passive ones, like television), increase dopamine in the reward center of the brain. Dopamine is known as the brain's 'feel good' chemical, but is also related to stress, addiction, anxiety, mood, and attention. Dopamine in excess can lead to psychotic symptoms--voices, delusions, paranoia, or confusion.”

So there you have it. Feel free to comment on this assertion. All contributions welcome.

Photo Credit: http://filmcrithulk.wordpress.com/

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

The New Highs: Are Bath Salts Addictive?

Part II.

Call bath salts a new trend, if you insist. Do they cause psychosis? Are they “super-LSD?” The truth is, they are a continuation of a 70-year old trend: speed. Lately, we’ve been fretting about the Adderall Generation, but every population cohort has had its own confrontation with the pleasures and perils of speed: Ritalin, ice, Methedrine, crystal meth, IV meth, amphetamine, Dexedrine, Benzedrine… and so it goes. For addicts: Speed kills. Those two words were found all over posters in the Haight Ashbury district of San Francisco, a few years too late to do the residents much good.

While the matter of the addictiveness of Spice and other synthetic cannabis products remains open to question, there no longer seems to be much doubt about the stimulant drugs known collectively as bath salts. To a greater or lesser degree, these off-the-shelf synthetic stimulants appear to be potentially addictive. And that’s not good news for anyone.

Last week, the U.S. Congress added 26 additional synthetic chemicals to the Controlled Substances Act, including the designer stimulants mephedrone and MDPV, at the behest of the Drug Enforcement

The research news on bath salts at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence (CPDD) in Palm Springs recently was complex and confusing. For example, the phemonenon of overheating, or hyperthermia, that plagues ravers on MDMA and sends some of them to the hospital is a function of certain temperature-sensitive effects of Ecstasy. But it is not as much of a problem with MDPV and mephedrone. The bath salts, like meth, don’t seem to cause overheating as readily.

On another front, William Fantegrossi, assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, told the panel audience that at very high doses and very high temperatures, stimulants like Ecstasy and MDPV “can cause self-mutilation in animals.” Fantegrossi’s statement was the closest anybody has come to providing a possible scientific basis for popular press accounts linking bath salts to flesh-eating frenzies by psychotic users. But this remains speculative, as there are still no reliable toxicological findings available in such cases.

The symposium on bath salts at the CPDD played to a packed conference hall, a sure sign that professional scientists who study addiction for a living were interested in the subject. The panel was titled “A Stimulating Soak in ‘Bath Salts’: Investigating Cathinone Derivative Drugs,” and was co-chaired by Dr. Michael Taffe of the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, CA, and pharmacology professor Dr. Annette Fleckenstein of the University of Utah.

Fantegrossi characterized the overall problem of designer stimulants as “dirty pharmacology” on both sides, pointing to the desperate efforts underway by government-funded scientists to “throw antagonists [blocking drugs] at these things.”

Alexander Shulgin, the grandfather of the modern psychedelic movement, popularized MDMA and hundreds of variants in his backyard laboratory in the Bay Area over the years. Shulgin, better than anyone, knew that legitimate research and dirty recreational chemistry are only a molecule away. In their book Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story, Alexander Shulgin and his wife Ana recall that cartoonist Gary Trudeau captured the truth of the situation as far back as 1985, when the MDMA story became front-page news:

Way back in mid-1985, the cartoonist-author of Doonesbury, Gary Trudeau, did a two-week feature on it, playing it humorous, and almost (but not quite) straight, in a hilarious sequence of twelve strips. On August 19, 1985 he had Duke, president of Baby Doc College, introduce the drug design team from USC in the form of two brilliant twins, Drs. Albie and Bunny Gorp. They vividly demonstrated to the enthusiastic conference that their new drug "Intensity" was simply MDMA with one of the two oxygens removed. "Voila," said one of them, with a molecular model in his hands, "Legal as sea salt."

Jeffrey Moran of the Arkansas Department of Health noted that despite the cat-and-mouse game continuously played between illegal drug designers and the law, government bans on mephedrone and MDPV, the two most common forms of designer stimulant, cause only temporary downturns in supply. They are no longer as legal as sea salt, but it doesn’t seem to matter. There are always new ones in the pipeline. Moran told the audience that at least 48 different compounds had been identified in more than 200 distinct bath salt-style products in his state alone. Sorting out the specific chemistry involves specialized assays designed to detect a bewildering array of molecules: methylone, mephedrone, paphyrone, butylone, 4-MEC, alpha-PVP, and a host of others, some old, some new, some reimagined by underground chemists.

Terry Boos of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency explained that most designer stimulants currently in play are not manufactured stateside. Most originate in Asia and arrive through various ports of call, where they are repackaged for sale in the U.S. Purity of the cathinone ranges from 30 to 95 per cent, Boos said.

Annette Fleckenstein of the University of Utah emphasized that scientists shouldn’t be fooled by overall structural similarities among such drugs as meth, mephedrone, MDMA, and MDPV. In a 2011 study published with her colleagues at the University of Utah, Fleckenstein lamented that mephedrone’s recent emergence on the drug scene had exposed the fact that “there are no formal pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic studies of mephedrone.”

But she has managed to show that methamphetamine causes lasting decreases in serotonin functions, as well as the better-known dopamine alterations, and that MDMA and mephedrone are intimately involved in the accumulation of serotonin in the brain’s nucleus accumbens, where addictive drugs produce many of their rewarding effects. “Rats will self-administer mephedrone,” said Fleckenstein—always a troubling clue that the drug in question may have addictive properties. Since the high in humans only last for three to six hours, there is a tendency to reinforce the behavior through repeated dosings.

Other behavioral clues have been teased out of rat studies. The Taffe Laboratory at Scripps Research Institute has focused on the cognitive, thermoregulatory, and potentially addictive effects of the cathinones. Rats will self-administer mephedrone, MDPV, and of course methamphetamine. However, Dr. Taffe told the audience that MDMA does not produce these classic locomotor stimulant effects at low doses and that it is “more difficult to get them to self-administer” Ecstasy. Nonetheless, Taffe told me he believes that MDMA is, in fact, potentially addictive. “Our data suggest that MDPV is highly reinforcing,” Taffe said in an email exchange after the conference, “and at least as readily self-administered as methamphetamine, at approximately the same per-infusion doses. But it is a very complicated story.”

Scripps researchers have carried the investigation forward with a new study, currently in press at the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Pai-Kai Huang and coworkers studied the differing effects of designer stimulants on voluntary wheel-running activity in rats, adding additional evidence to the basic behavioral split among club drugs of the moment. Taffe, one of the study’s co-authors, said the researchers had predicted that the two drugs with the strongest serotonin activity—MDMA and the mephedrone variants—would decrease wheel running activity in the rats. Methedrine and MDPV, they predicted, would increase activity.

And that’s how it turned out. What that means for human users is still not entirely clear. But MDPV in particular, it now seems evident, has some rather direct and disturbing affinities with crystal meth and cocaine. And the vagaries of the market have led to sharp increases in the percentage of MDPV found in bath salt products in the last two years. Are we seeing the wholesale replacement of MDMA by a more directly addictive, methedrine-like drug? Will we see a rise in psychotic symptoms, and increased visits to the ER, as MDPV becomes more common in bath salts? Ecstasy has been implicated in the death of users as well, but will the surge in cathinone drugs mean there will be additional deaths?

And remember: Researchers are able to distinguish between rats under the influence of either MDMA- or MDPV-based wheel activity—but the research suggests that under blinded conditions, human users aren’t very good at guessing which of those two drugs they’re on. Furthermore, we don’t have the data to say whether users can tell mephedrone from MDPV in a blind test. And even wheel-running rats don’t give away whether they’re running on MDMA or mephedrone. These categorical distinctions are all-important, but still in relative infancy as far as street use is concerned.

The Scripps scientists concluded that their study “underlines the error of assuming all novel cathinone derivative stimulants that become popular with recreational users will share neuropharmacological or biobehavioral properties.” Some of the combinations produce a “unique constellation of desired effects.”

But by 2011, the U.S. media had conflated mephedrone with MDPV and half a dozen other substances, all with differing effects on users. For public health officials, it was a nightmare.

“We know that MDMA users follow the science,” Taffe said, at the close of the bath salts panel. “So information we make available can have a direct effect on public health for those people.” But for bath salt users, the picture is not as clear. Consider, once again, Arkansas’ finding of 30 or 40 different cathinone derivatives, part of a set of 250 distinct chemicals identified in different combinations of bath salt products. “Slight modifications can change the toxicities,” Taffe said. “Abuse liabilities differ between MDMA and different cathinones. They all confer different health risks.”

One of the primary drivers of bath salt usage appears to be the desire to finesse drug-testing programs. And if drug-testing programs are pushing people in the direction of more dangerous, unfamiliar, and addictive substances, then perhaps drug testing is part of the problem rather than the solution.

In the short run, emergency treatment of patients with OD symptoms they attribute to bath salts will remain the same, whether the cathinone in question is mephedrone, MDPV, or some other variant. General emergency-department procedures for stimulant intoxication are standardized. People can suffer cardiac arrest from either MDMA or meth. And people can run very high temperatures with overdoses of any of these stimulants.

Are users listening? Do they believe any of the health warnings this time out, or have there been too many over the years, always strident and hysterical and overinflated?

Huang PK, Aarde SM, Angrish D, Houseknecht KL, Dickerson TJ, & Taffe MA (2012). Contrasting effects of d-methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone, and 4-methylmethcathinone on wheel activity in rats. Drug and alcohol dependence PMID: 22664136

Hadlock GC, Webb KM, McFadden LM, Chu PW, Ellis JD, Allen SC, Andrenyak DM, Vieira-Brock PL, German CL, Conrad KM, Hoonakker AJ, Gibb JW, Wilkins DG, Hanson GR, & Fleckenstein AE (2011). 4-Methylmethcathinone (mephedrone): neuropharmacological effects of a designer stimulant of abuse. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics, 339 (2), 530-6 PMID: 21810934

Labels:

4-MMC,

bath salts,

cathinones,

designer stimulant,

MDMA,

MDPV,

mephedrone,

meth,

methamphetamine

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Energy Drinks: What’s the Big Deal?

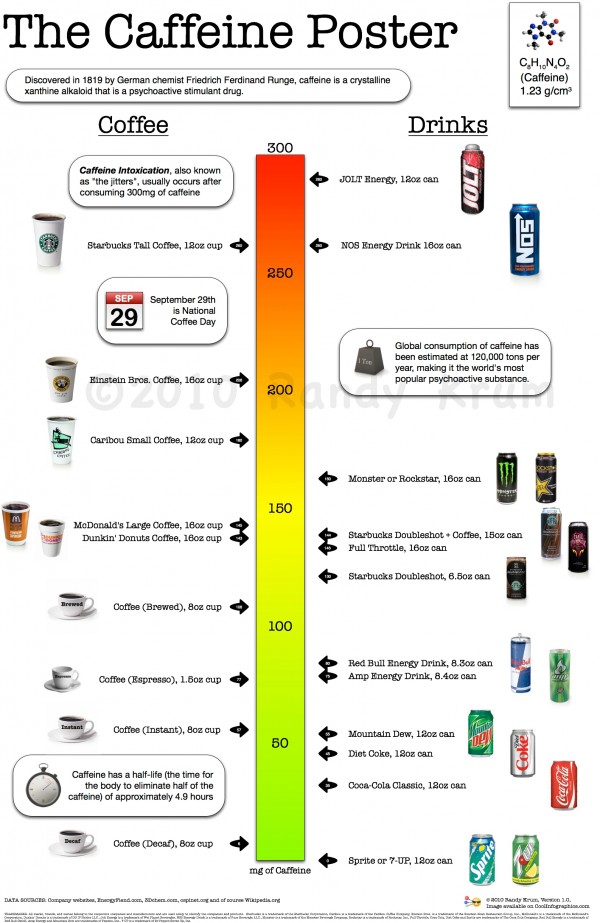

Are energy drinks capable of pushing some people into caffeine-induced psychotic states? Some medical researchers think so, under the right set of conditions.

Red Bull, for all its iconic ferocity, is pretty tame, weighing in at approximately half a cup of coffee. Drinks like Monster Energy and Full Throttle push it up to 100-150, or the equivalent of a full cuppa joe, according to USDA figures at Talk About Coffee. That doesn’t sound so bad—unless you’re ten years old. A little caffeine might put you on task, but an overdose can leave you scattered and anxious—or worse. If you cut your teeth on Coke and Pepsi, then two or three energy drinks can deliver an order-of-magnitude overdose by comparison.

Readers are entitled to ask: Are you serious? Can’t we just ignore the inevitable view-this-with-alarm development in normal kid culture, and move on?

My interest began when I ran across a 2009 case report in CNS Spectrums, describing an apparent example of “caffeine-induced delusions and paranoia” in a very heavy coffee drinking farmer. “Convinced of a plot against him,” the psychologists write, “he installed surveillance cameras in his house and on his farm…. He became so preoccupied with the alleged plot that he neglected the business of the farm…. and he had his children taken from him because of unsanitary living conditions.”

The patient was not known to be a drinker, reporting less than a case of beer annually. He had shown no prior history of psychotic behaviors. But for the past  seven years, he had been consuming about 36 cups of coffee per day, according to his account. Take that number of cups times 125 milligrams, let’s say, for a daily total of 4500 milligrams. At that level, he should be suffering from panic and anxiety disorders, according to caffeine toxicity reports, and he would be advised to call the Poison Control Center. And that certainly seems to have been the case. “At presentation,” the authors write, “the patient reported drinking 1 gallon of coffee/day.”

seven years, he had been consuming about 36 cups of coffee per day, according to his account. Take that number of cups times 125 milligrams, let’s say, for a daily total of 4500 milligrams. At that level, he should be suffering from panic and anxiety disorders, according to caffeine toxicity reports, and he would be advised to call the Poison Control Center. And that certainly seems to have been the case. “At presentation,” the authors write, “the patient reported drinking 1 gallon of coffee/day.”

On the one hand, the idea of caffeine causing a state resembling chronic psychosis is the stuff of sitcoms. On the other hand, metabolisms do vary, and the precise manner in which coffee stimulates adenosine receptors can lead to anxiety, aggression, agitation, and other conditions. Could caffeine, in an aberrant metabolism, break over into full-blown psychosis? At the Caffeine Web, where psychiatrists and toxicologists duke it out over all things caffeinated, Sidney Kay of the Institute of Legal Medicine writes: “Coffee overindulgence is overlooked many times because the bizarre symptoms may resemble and masquerade as an organic or mental disease.” Symptoms, he explains, can include "restlessness, silliness, elation, euphoria, confusion, disorientation, excitation, and even violent behavior with wild, manic screaming, kicking and biting, progressing to semi-stupor.”

That doesn’t sound so good. In “Energy drinks: What is all the hype?” Mandy Rath examines the question in a recent issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Health Practitioners.

Selling energy drinks to kids from 6 to 19 years old is a $3.5 billion annual industry,Rath asserts. And while “most energy drinks consumed in moderation do not pose a huge health risk,” more and more youngsters are putting away higher and higher doses of caffeine. At the level of several cans of Coke, or a few cups of strong coffee or, an energy drink or three, students can expect to experience improved reaction times, increased aerobic endurance, and less sleepiness behind the wheel. Most people can handle up to 300 mg of caffeine in a concentrated blast. Certainly a better bargain, overall, than three or four beers.

But first of all, you don’t need high-priced, caffeine-packed superdrinks to achieve that effect. A milligram of caffeine is a milligram of caffeine. But wait, what about the nifty additives in Full Throttle and Monster and Rockstar? The taurine and… stuff. Taurine is an amino acid found in lots of foods. Good for you in the abstract. Manufacturers also commonly add sugar (excess calories), ginseng (at very low levels), and bitter orange (structurally similar to norepinephrine). However, the truly interesting addition is guarana, a botanical product from South America. When guarana breaks down, it’s principal byproduct is, yes, caffeine. Guarana seeds contain twice the caffeine found in coffee beans. Three to five grams of guarana provide 250 mg of caffeine. Energy drink manufacturers don’t add that caffeine to the total on the label because—oh wait, that’s right, because makers of energy drinks, unlike makers of soft drinks, don’t have to print the amount of caffeine as dietary information. And on an ounce-for-pound basis, kids are getting a lot more caffeine with the new drinks than the older, labeled ones.

All of this increases the chances of caffeine intoxication. Rath writes that researchers have identified caffeine-related increases among children in hypertension, insomnia, motor tics, irritability, and headaches. Chronic caffeine intoxication results in “anxiety, emotional disturbances, and chronic abdominal pain.” Not to mention cardiac arrhythmia, seizures, and mania.

So what have we learned, kids? Energy drinks are safe—if you don’t guzzle several of them in a row, or substitute them for dinner, or have diabetes, or an ulcer, or happen to be pregnant, or are suffering from heart disease or hypertension. And if you do OD on high-caffeine drinks, it will not be pleasant: Severe palpitations, panic, mania, muscle spasms, etc. Somebody might even want to take you to the emergency room. Coaches and teachers need to keep a better eye out for caffeine intoxication.