Move by Pennsylvania supermarkets sparks controversy.

Saturday, August 7, 2010

Swipe, Smile, Breathe: Wine Vending Machines in the USA.

Move by Pennsylvania supermarkets sparks controversy.

Pennsylvania, one of the last few states in the nation where liquor sales are state-controlled, has kicked off a plan to sell wine in grocery stores via vending machines. Consumers would need a valid I.D., a matching picture taken by an onsite video camera, and a puff of breath in the direction of a no-touch air sensor to complete the purchase.

Whether you consider this a convenient or a cumbersome way to buy your bottle of Chianti for the evening’s meal, many Pennsylvanians seem supportive, according to news reports, if only because it saves them a trip to a state-run liquor outlet. Grocery stores cannot sell wine off the shelf under the rules of the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board (PLCB).

Japan and Europe have beer vending machines, but the two prototype machines now in Pennsylvania are believed to be the first supermarket wine kiosks in the U.S.

A spokesman for the ISSU, the union representing state liquor store managers, complained that “cigarettes are banned from being sold in vending machines in Pennsylvania supermarkets and yet Americans’ number one drug of choice will now be vended only in Pennsylvania by the PLCB.”

Putting it a bit more directly, the union’s vice president, David Wanamaker, said: “Alcohol is not a Red Box DVD—it is the most abused drug in every town, city and state in the USA.”

Keith Wallace, president of the Wine School of Philadelphia, had other objections. “The process is cumbersome and assumes the worst in Pennsylvania’s wine consumers—that we are a bunch of conniving underage drunks,” he told Kathy Matheson of The Associated Press. Liquor board members, he added, “are clearly detached from reality of they think these machines offer any value to the consumer.”

And the CEO of the Wine and Spirits Wholesalers of America, presumably with a straight face, chipped in with concerns about the machine’s ability to prevent sales to minors.

One of the major drawbacks is that the kiosk is not really a genuine vending machine, but rather a large box full of wine bottles, attached to a camera, with a live person at the other end—a state employee in Harrisburg who approves each and every remote sale only after verifying a visual match with the photo I.D.

The wine vending machines represent “a technology kludge for bad laws,” and “an attempt to solve the age-old problem of underage drinking with new technology” according to Damon Brown at BNET.

Brown offers 3 suggestions:

--Facial recognition software—“A much more reasonable solution for the vending machines than a person sitting on the other end of a camera.”

--Program tweaks—“Japan now gives out magnetic strips that, when placed on IDs, allow customers to confirm their identity… Pennsylvania has spent money on the machines, but hasn’t come up with an elegant solution to identity.”

--Just change the law—Most state allow wine sales in grocery stores, and the earth hasn’t cleaved in twain. This Rube Goldberg-style contraption, as the store managers union has characterized it, has yet to prove that it is worth the money.

Photo Credit: http://wduqnews.blogspot.com

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

Cannabis Receptors and the “Runner’s High”

Maybe it isn't endorphins after all.

What do long-distance running and marijuana smoking have in common? Quite possibly, more than you’d think. A growing body of research suggests that the runner’s high and the cannabis high are more similar than previously imagined.

The nature of the runner’s high is inconsistent and ephemeral, involving several key neurotransmitters and hormones, and therefore difficult to measure. Much of the evidence comes in the form of animal models. Endocannabinoids—the body’s internal cannabis—“seem to contribute to the motivational aspects of voluntary running in rodents.” Knockout mice lacking the cannabinioid CB1 receptor, it turns out, spend less time wheel running than normal mice.

A Canadian neuroscientist who blogs as NeuroKuz suggests that “a reduction in CB1 levels could lead to less binding of endocannabinoids to receptors in brain circuits that drive motivation to exercise.” NeuroKuz speculates on why this might be the case. Physical activity and obtaining rewards are clearly linked. The fittest and fleetest obtain the most food. “A possible explanation for the runner’s high, or ‘second wind,’ a feeling of intense euphoria associated with going on a long run, is that our brains are stuck thinking that lots of exercise should be accompanied by a reward.”

In 2004, the British Journal of Sports Medicine ran a research review, “Endocannabinoids and exercise,” which seriously disputed the “endorphin hypothesis” assumed to be behind the runner’s high. To begin with, other studies have shown that exercise activates the endocannabinoid system.

“In recent years,” according to the authors, “several prominent endorphin researchers—for example, Dr Huda Akil and Dr. Solomon Snyder—have publicly criticised the hypothesis as being ‘overly simplistic,’ being ‘poorly supported by scientific evidence’, and a ‘myth perpetrated by pop culture.’” The primary problem is that the opioid system is responsible for respiratory depression, pinpoint pupils, and other effects distinctly unhelpful to runners.

The investigators wired up college students and put them to work in the gym, and found that “exercise of moderate intensity dramatically increased concentrations of anandamide in blood plasma.” The researchers break the runner’s high into four major components. Exercise, they say, “suppresses pain, induces sedation, reduces stress, and elevates mood.” Some of the parallels with the cannabis high are not hard to tease out: “Analgesia, sedation (post-exercise calm or glow), a reduction in anxiety, euphoria, and difficulties in estimating the passage of time.”

There are cannabinoid receptors in muscles, skin and the lungs. Intriguingly, the authors suggest that unlike “other rhythmic endurance activities such as swimming, running is a weight bearing sport in which the feet must absorb the ‘pounding of the pavement.’” Swimming, the authors speculate, “may not stimulate endocannabinoid release to as great an extent as running.” Moreover, “cannabinoids produce neither the respiratory depression, meiosis, or strong inhibition of gastrointestinal motility associated with opiates and opioids. This is because there are few CB1 receptors in the brainstem and, apparently, the large intestine.”

A big question remains: What about running and the “motor inhibition” characteristic of high-dose cannabis? (An inhibition that may make cannabis useful in the treatment of movement disorders like tremors or tics.) Running a marathon is not the first thing on the minds of most people after getting high on marijuana. The paper maintains, however, that at low doses, “cannabinoids tend to produce hyperactivity,” at least in animal models. The CB1 knockout mice were abnormally inactive, due to the effect of cannabinoids on the basal ganglia. Practiced, automatic motor skills like running are controlled in part by the basal ganglia. The authors predict that “low level skills such as running, which are controlled to a higher degree by the basal ganglia than high level skills, such as basketball, hockey, or tennis, may more readily activate the endocannabinoid system.”

The authors offer other intriguing bits of evidence. Anandamide, one of the brain’s own cannabinoids, “acts as a vasodilator and products hypotension, and may thus facilitate blood flow during exercise.” In addition, “endocannabinoids and exogenous cannabinoids act as bronchodilators” and could conceivably facilitate breathing during steady exercise. The authors conclude: “Compared with the opioid analgesics, the analgesia produced by the endocannabinoid system is more consistent with exercise induced analgesia.”

Photo Credit: http://www.madetorun.com/

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Multiple Addictions

Why isn’t one drug enough?

The newer views of addiction as an organic brain disorder have cast strong doubt on the longstanding assumption that different kinds of people become addicted to different kinds of drugs. As far back as 1998, the Archives of General Psychiatry flatly stated: “There is no definitive evidence indicating that individuals who habitually and preferentially use one substance are fundamentally different from those who use another.” This quiet but highly influential breakthrough in the addiction paradigm has paid enormous dividends ever since.

The behaviors known as pan-addiction, substitute addiction, multiple addiction, and cross-addiction demonstrate that some addicts are vulnerable in an overall way to other addictive drugs as well. If it was one addiction at a time, that was known as substitute addiction. If it was many addictions simultaneously, researchers called it pan-addiction. The fact that a striking number of alcoholics also had cigarette addictions, and were heavy coffee drinkers, or had been addicted sequentially or simultaneously to various illegal addictive drugs—this was no great secret in the addiction therapy community. Indeed, it was clear that many addicts preferred the mix of two or more addictive drugs. And the phenomenon has serious social and economic ramifications.

Addicts show a remarkable ability to shift addictions, or to multiply them. Many addicts seem to be able to use whatever was readily at hand—alcoholics turning to cough syrup or doctor-prescribed morphine; pill poppers switching to alcohol; cocaine addicts turning to pot. If addiction was really, at bottom, a metabolic tendency rather than a sociological aberration, then it could conceivably express itself as a propensity to become seriously hooked on any drug that afforded enough pleasurable reinforcement to be considered addictive.

One leading school of thought views the metabolic disorder we call addiction as a manifestation of an “impaired reward cascade response.” This fact matters more than the differing details of addictive drugs themselves. This is where and how addiction happens. It is understood that addiction has its cognitive and environmental aspects as well, but the scientific mystery of how normal people become uncontrollable addicts has been substantially explained. Addictive drugs are a way of triggering the reward cascade. Cocaine, cocktails, and carbo-loading were all short-term methods of either supplying artificial amounts of these neurotransmitters, or sensitizing their receptors, in a way that produced short-term contentment in people whose reward pathway did not operate normally.

Naturally, you have to allow for environmental and social factors, but no matter how you add it up, a certain number of people are going to get into trouble with drugs and alcohol—it doesn’t really matter which drugs or what kind of alcohol. And a percentage of that percentage was going to get into trouble very quickly. These were the people who were hard to treat, and seriously prone to relapse. They would get into trouble because drugs did not have the same effect on them that they had on other people. Like a virus infecting a suitable host, drugs—any addictive drug--went to work on those kinds of addicts in a hurry.

Graphics Credit: http://comingcleantogether.wordpress.com/

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Last Call: Book Review

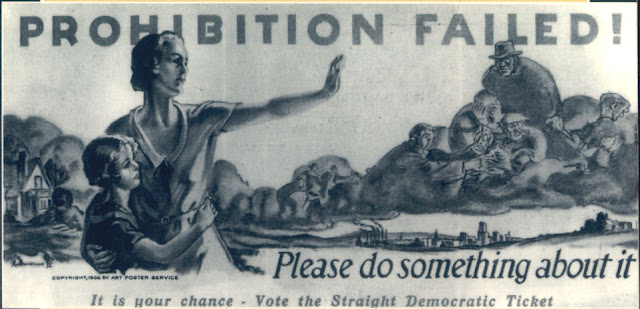

Lessons of Prohibition as timely as ever.

It gained serious momentum with the creation of the Anti-Saloon League, the most powerful pressure group in American history. It took down the 5th largest industry in the nation. Financed heavily by teetotaler John D. Rockefeller, it lasted 14 years, and it is mind boggling to contemplate the parallels with the current drug war.

On January 16, 1920, with the official passage of the 18th Amendment banning the manufacture, sale, or transport of alcoholic beverages, America carved out only the second explicit limitation on the activities of its citizens in the Republic’s history. As Daniel Okrent writes in his definitive history, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, “you couldn’t own slaves, and you couldn’t buy alcohol.”

Americans in the late 1800s drank a lot of alcohol. “Multiply the amount American’s drink today by three,” says Okrent. Taxes on whiskey and beer helped pay for the War of 1812 and the Civil War. By the end of the 19th Century, consumption of distilled spirits, particularly whiskey, had been partially replaced by…. beer! It was German immigrant brewers who cornered the market for “liquid bread,” as beer was sometimes known. (Italians who migrated to California sparked Napa Valley’s wine industry.)

Who had the power to take on the brewers and distillers of America in a fight to the finish over alcohol? According to Okrent, the answer was: white Anglo-Saxon protestant women. And not just the well-publicized “hatchetation” of Carrie Nation and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. In fact, the women’s suffrage movement and the drive for prohibition were inextricably linked. The fact of alcohol in family life was one of the reasons women wanted “the right to own property, and to shield their families’ financial security from the profligacy of drunken husbands.” As famed alcoholic Jack London observed, “the moment women get the vote in any community, the first thing they proceed to do is close the saloons.” At least, so London hoped—he thought perhaps prohibition might save his life.

Lamentably, women were joined by racists and nativists in the fight against alcohol and its alleged grip on “the infidel foreign population of our country.” On the Iron Range of northern Minnesota, “congressional investigators counted 256 saloons in fifteen mining towns, their owners representing eighteen distinct immigrant nationalities.” After the United States entered World War I, the Anti-Saloon League stoked anti-German feeling as part of the Prohibition strategy. It was “native-born Protestants against everybody else,” Okrent writes. Demonizing foreigners was and is a useful strategy in any prohibition campaign.

In California, vintners exploited the so-called fruit juice clause in the Volstead Act, the enabling legislation for the 18th amendment. During the California Grape Rush of 1920, “Grapes are so valuable this year that they are being stolen, a Napa Valley newspaper lamented. The fruit juice clause was intended to allow farmer’s wives to “conserve their fruit” by fermenting the apple crop into hard cider.

A second useful loophole for grape growers was an exemption in the Volstead Act, allowing wine use for “sacramental purposes” during Catholic and Jewish ceremonies. A “dry” Methodist dentist promptly responded with a Protestant version: Welch’s Grape Juice.

The third major exception covered the legal distribution of alcoholic beverages “for medicinal purposes”—the only exemption for hard liquor. Clearly, alcohol in its many forms was a necessary part of practicing medicine. But “beverage alcohol” was a different story. Nonetheless, doctors wrote prescriptions for alcohol on government-issued prescription forms, and, despite initial opposition, the American Medical Association (AMA) eventually discovered 27 different medical conditions, ranging from diabetes to old age, which might benefit from the alcohol treatment, arguing that any interference with the medicinal use of liquor would be “a serious interference with the practice of medicine.”

It made for a strange set of bootlegging bedfellows: Rabbis, priests, farmer’s wives, doctors—and Al Capone. Meanwhile, alcohol poured over the border from Canada, came to the coast in ships from the Bahamas, and was offloaded in Seattle from smugglers on land and sea. As one prominent “wet” complained, Prohibition had become “an attempt to enthrone hypocrisy as the dominant force in this country.”

Prohibition even had its own version of “3 Strikes” legislation, called the Jones Law, which imposed up to a five-year sentence for first violations. Lansing, Michigan, passed an ordinance calling for mandatory life in prison for a fourth violation. One effect of such harsh laws was to force out small-time bootleggers, clearing the field for the major operators, like the Bronfman family and its Seagram’s brand of whiskey in Canada.

In the end, as the saying went, “Prohibition was better than no liquor at all.” Yet overall consumption of alcohol did decline, particularly during the early years. Things began to change by the late 1920s, though, as the drys pushed “the limits of law’s ability to defeat appetite.” Part of the problem, Okrent believes, was simple: “Drys didn’t understand drinkers, in scores of different ways.”

“By one accounting, U.S. attorneys across the country spent, at minimum, 44 percent of their time and resources on Prohibition prosecutions—if that was the word for the pallid efforts they were able to sustain on such limited resources,” Okrent writes, again with application to the present state of affairs. In Alabama, prohibition prosecutions accounted for 90 percent of the federal court’s workload. And all this at a time when the federal government had lost more than $440 million in liquor tax revenues, much of which ended up in the pockets of foreign-born criminals. By 1926, bootleg liquor sales were estimated at $3.6 billion nationally, “almost precisely the same as the entire federal budget that year.”

Not a pretty picture. “The business pays very well,” as attorney Clarence Darrow put it, “but it is outside the law and they can’t got to court.” As a result, Darrow said, “they naturally shoot.”

The head of the DuPont family suggested that liquor tax revenues “would be increased sufficiently to warrant the abolition of the income tax and corporation tax,” similar to today’s argument that, by ending drug prohibition, California and other states can balance their precarious budgets.

By the late 1920s, it was said, the only groups who continued to favor Prohibition were evangelical Christians and bootleggers. In 1929, following the Crash and the beginning of the Great Depression, with banks folding and unemployment soaring, “any remaining ability to enforce Prohibition evaporated.” The Repeal movement promised that with the end of Prohibition, the Depression “will fade away like the mists before the noonday sun.” That didn’t happen. But in the first post-repeal year, the government took in more than $250 million in liquor taxes, representing about 9 percent of total federal revenue.

Photo Credit: http://www.druglibrary.org/

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

U.S. Leads World in Prescription Drug Use

It’s complicated.

Wait, wait, it’s a good thing. Mostly. Or maybe.

While the headline may suggest a story that is either shocking or self-evident, depending upon your point of view, the British study it refers to is based on the level of uptake of prescription drugs for 14 different diseases in 14 different countries. It is not a study of prescription drug abuse, but rather a look at legitimate medical treatment of diseases like cancer, multiple sclerosis, and Hepatitis C.

Measured by volume of use per capita, Americans consume more prescription drugs than any other country. We’re number one! They can’t touch us! (Spain ranked second, and France was third. New Zealand, Sweden, and Germany ranked at the bottom.)

Seriously, though, we mostly knew that about America already. Another way to look at these numbers is to turn the question around: Why, for example, is the UK in 10th place for cancer drug usage, despite near-universal health coverage? Why aren’t other countries dispensing larger amounts of recognized medications for such diseases as Hepatitis C and rheumatoid arthritis? So, one question the report seems to raise is: why do other developed countries have worse access to prescription drugs than we do?

UK Health Secretary Andrew Lansley, quoted in an article for Nature News, stressed that “high usage does not necessarily equal good performance, nor does low usage indicate a failing.” At the same time, however, Lansley announced a new government fund of 50 million English pounds “to increase access to cancer drugs.”

With those caveats in mind, we find that the report concludes… well, in the end, the report acknowledges the wide variations in international usage, but concludes that “there does not appear to be a consistent pattern between countries or for different disease areas or categories of drug.” The study group did not find any uniform patterns that held across drug categories or disease regions. In fact, the report invites interested stakeholders to submit their best thoughts on the matter to internationaldruguse@dh.gsi.gov.uk

Despite this absence of firm conclusions or hypotheses, the report does manage to note some common themes:

-- “Differences in health spending and systems do not appear to be strong determinants of usage.” But even here, the report goes on to offer some thoughts on the dominance of the U.S. “For example, ‘supplier-induced demand’ was felt to be a greater issue in the USA because of the payment structures in that country: where suppliers can charge more for delivering a particular treatment, this may provide perverse incentives to prescribe those drugs.” And: “The majority of countries reviewed provide (almost) universal coverage, with residence in the given country being the most common basis for entitlement to healthcare. The USA is the only country not offering universal access to healthcare; entitlement to publicly funded services is dependent on certain conditions…”

--“Clinical culture and attitudes towards treatment remain important determinants in levels of uptake.” The same reasoning would apply to the U.S., as psychotherapists have struggled for a foothold in the brave new world of medications for diseases with strong mental and emotional components.

--“A country that spends more on healthcare or a country which operates few controls on prescribing could be expected to use more drugs.” But I thought the report said that differences in health spending and systems didn’t make any difference…

Here is the problem with attempts at surveys of this kind. (Departments at the United Nations do a lot of them, as do individual countries.) Mike Richards, the UK’s National Cancer Director, compiled the report--“Extent and causes of international variations in drug usage”—and further qualified the findings: “For some disease areas, high usage may be a sign of weaknesses at other points in the care pathway and low usage a sign of effective disease prevention.”

It is similar to the problem of quantifying addiction. The amount of addictive drug consumed often tells us very little about the problem, or the prospects for amelioration. However, in a survey like this one, I think coming out on the top is, on balance, better than coming out on the bottom.

Saturday, July 24, 2010

Heroin in Vietnam: The Robins Study

Origins of the Disease Model of Addiction (Part 2).

In 1971, under the direction of Dr. Jerome Jaffe of the Special Action Office on Drug Abuse Prevention, Dr. Lee Robins of Washington University in St. Louis undertook an investigation of heroin use among young American servicemen in Vietnam. Nothing about addiction research would ever be quite the same after the Robins study. The results of the Robins investigation turned the official story of heroin completely upside down.

The dirty secret that Robins laid bare was that a staggering number of Vietnam veterans were returning to the U.S. addicted to heroin and morphine. Sources were already reporting a huge trade in opium throughout the U.S. military in Southeast Asia, but it was all mostly rumor until Dr. Robins surveyed a representative sample of enlisted Army men who had left Vietnam in September of 1971—the date at which the U.S. Army began a policy of urine screening. The Robins team interviewed veterans within a year after their return, and again two years later.

After she had worked up the interviews, Dr. Robins, who died in 2009, found that almost half—45 per cent—had used either opium or heroin at least once during their tour of duty. 11 per cent had tested positive for opiates on the way out of Vietnam. Overall, about 20 per cent reported that they had been addicted to heroin at some point during their term of service overseas.

To put it in the kindest possible light, military brass had vastly underestimated the problem. One out of every five soldiers in Vietnam had logged some time as a junky. As it turned out, soldiers under the age of 21 found it easier to score heroin than to hassle through the military’s alcohol restrictions. The “gateway drug hypothesis” didn’t seem to function overseas. In the United States, the typical progression was assumed to be from “soft” drugs (alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana) to the “hard” category of cocaine, amphetamine, and heroin. In Vietnam, soldiers who drank heavily almost never used heroin, and the people who used heroin only rarely drank. The mystery of the gateway drug was revealed to be mostly a matter of choice and availability. One way or another, addicts found their way to the gate, and pushed on through.

“Perhaps our most remarkable finding,” Robins later noted, “was that only 5% of the men who became addicted in Vietnam relapsed within 10 months after return, and only 12% relapsed even briefly within three years.” What accounted for this surprisingly high recovery rate from heroin, thought to be the most addictive drug of all? As is turned out, treatment and/or institutional rehabilitation didn’t make the difference: Heroin addiction treatment was close to nonexistent in the 1970s, anyway. “Most Vietnam addicts were not even detoxified while in service, and only a tiny percentage were treated after return,” Robins reported. It wasn’t solely a matter of easier access, either, since roughly half of those addicted in Vietnam had tried smack at least once after returning home. But very few of them stayed permanently readdicted.

Any way you looked at it, too many soldiers had become addicted, many more than the military brass had predicted. But somehow, the bulk of addicted soldiers toughed their way through it, without formal intervention, after they got home. Most of them kicked the habit. Even the good news, then, took some getting used to. The Robins Study painted a picture of a majority of soldiers kicking it on their own, without formal intervention. For some of them, kicking wasn’t even an issue. They could “chip” the drug at will—they could take it or leave it. And when they came home, they decided to leave it.

However, there was that other cohort, that 5 to 12 per cent of the servicemen in the study, for whom it did not go that way at all. This group of former users could not seem to shake it, except with great difficulty. And when they did, they had a very strong tendency to relapse. Frequently, they could not shake it at all, and rarely could they shake it for good and forever. Readers old enough to remember Vietnam may have seen them at one time or another over the years, on the streets of American cities large and small. Until quite recently, only very seriously addicted people who happened to conflict with the law ended up in non-voluntary treatment programs.

The Robins Study sparked an aggressive public relations debate in the military. Almost half of America’s fighting men in Vietnam had evidently tried opium or heroin at least once, but if the Robins numbers were representative of the population at large, then relatively few people who tried opium or heroin faced any serious risk of long-term addiction. A relative small number of users were not so fortunate, as Robins noted. What was the difference?

Quotes from: Robins, Lee N. (1994). “Lessons from the Vietnam Heroin Experience.” Harvard Mental Health Letter. December.

See also:

Robins, Lee. N. (1993) “Vietnam veterans' rapid recovery from heroin addiction: a fluke or normal expectation?” Addiction. 88(8), 1037 – 1167.

Origins of the Disease Model of Addiction (Part 1) can be found HERE.

Photo Credit: soldiersupportproject.org

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Methland: Book Review

Cooking crystal in the heart of the Heartland.

It’s summer, and I’ve been catching up on my reading. In an earlier post, I reviewed Joshua Lyon’s memoir of prescription drug addiction, Pill Head. This time, we travel to the opposite end of the spectrum and take a look at Methland, Nick Reding’s journalistic account of crystal meth addiction in the small farming community of Oelwein, Iowa.

This is a tale not far from my heart or home. I was born in Iowa and lived there until I was 21. A few years ago, the small Iowa town where my parents live was rocked by a series of revelations about a local lawyer’s ties to a major methedrine operation. Money had flowed through my parent’s small town in ways never seen before.

Also a few years ago, a Chippewa Indian was bound to a chair in the woods, tortured, and finally murdered in a dispute with meth dealers over some missing money. This happened about 30 miles from my home in rural Minnesota. It happened about an hour’s drive from the birthplace of Bob Dylan. It happened in a place where such things just don’t happen.

In a bleak nutshell, Reding lays out how it went down: During the lifetime of the average Baby Boomer, the amphetamine picture has evolved from the classic long-haul trucker’s Benzedrine and Dexedrine to the tweaker’s bathtub crank and crystal meth. “Not only in Oelwein, but all across Iowa, meth had become one of the leading growth sectors of the economy. No legal industry could, like meth, claim 1,000 percent increases in production and sales in the four years between 1998 and 2002, a period in which corn prices remained flat and beef prices actually fell.” In 2004, law enforcement officials busted a total of 1,370 methamphetamine labs in Iowa.

We learn about Jarvis, an Oelwein meth cook who became a local legend by staying awake on speed for 28 days, or, as Reding puts it, “an entire lunar cycle.” We hear about two-year old Buck, Iowa’s most famous meth baby, whose hair, when tested at the behest of the state Department of Human Services, recorded the highest cell follicle traces of speed ever found in an Iowa child (“At least 7,000 kids were living every day in homes that produce five pounds of toxic waste, which is often just thrown in the kitchen trash, for each pound of usable methamphetamine”). And there is the local doctor, forced to deal with meth addicts while battling his own alcohol and nicotine addictions. The doctor refers to the town’s many bars as “unsupervised outpatient stress-reduction clinics that serve cheap over-the-counter medications with lots of side effects.”

The local prosecuting attorney, we learn, has turned to Kant for solace. “So you can put a tweaker in prison,” he tells the author, “and the whole time he’s in there, he’s thinking of only one thing: how he’s going to get high the day he’s out. He’s not even thinking about it, actually. He’s like, rewired to KNOW that everything in life is about the drug. So you say, ‘What good does prison do?’”

The switch from ephedrine to pseudoephedrine as a main ingredient—an artful end run around loophole-ridden legislation—was the “blockbuster moment in the modern history of the meth epidemic,” Reding writes. “This, really, is the genius of the meth business. Cocaine and heroin are linked to illegal crops—coca and poppies respectively. Meth on the other hand is linked in a one-to-one ratio with fighting the common cold.” Moreover, half of the world’s pseudoephedrine supply is manufactured in China, far from the effective reach of U.S. law enforcement.

Not all of Iowa’s meth is homemade. California is the link between Iowa meth and the Drug War. A DEA officer tells Reding: “Our success with Medellin and Cali essentially set the Mexicans up in business, at a time when they were already cash-rich thanks to the budding meth trade in Southern California.”

The connection between Iowa meth, immigration problems, and the food industry is a bit subtler. Agribusiness consolidation in food packaging and processing—particularly meat packing--led to the demand for cheaper labor, which lead to an influx of south-of-the-border immigrants, legal and illegal, to many of Iowa’s small towns. “The real impetus to walk across the desert: Cargill-Excel in Ottumwa is always hiring,” Reding notes. Narcotics and poverty, says the author, mutually reinforce one another.

Graphics Credit: http://abouttheaddict.wordpress.com/

Labels:

Iowa meth,

meth addiction,

meth babies,

methampthetamine,

methland

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)