Showing posts with label Volstead Act. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Volstead Act. Show all posts

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Prohibition in Perspective

An essay on the Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914.

As the 20th Century began, America’s drinking habits were undergoing a thorough review. But In late 1914, five years before the prohibition of alcohol became the law of the land, the government also took aim at other drugs. The legal status of heroin and cocaine changed overnight with the passage of the Harrison Narcotic Act. The U.S. Congress, with the vociferous backing of William Jennings Bryan, the prohibitionist Secretary of State, voted to ban the “non-medical” use of opiates and derivatives of the coca plant.

Under the Harrison Act, physicians could be arrested for prescribing opiates to patients. “Honest medical men have found such handicaps and dangers to themselves and their reputation in these laws,” railed an editorial in the National Druggist, “that they have simply decided to have as little to do as possible with drug addicts...” The Harrison Act did have the effect of weeding out casual users, as opium became dangerous and expensive to procure. Housewives, merchants, salesmen, and little old ladies who had been indulging in the “harmless vice” now gave it up.

By 1919, continued pressure from the alcohol temperance movement culminated in Congressional passage of the Volstead Act, which provided for federal enforcement of alcohol prohibition. The temperance activists had pulled it off, though there is nothing very “temperant” about total prohibition. A year later, the states ratified the 18th Amendment. Within a five-year period, morphine, cocaine, and alcohol had all been banned in America. The Prohibition Era had begun. At roughly the same time, alcohol prohibition movements were sweeping across Europe, Russia, and Scandinavia, as evidenced by this 1921 news photograph of Chinese Maritime Officers with 300 lbs of smuggled morphine confiscated in cylinders shipped from Japan.

Prohibition and the passage of the Harrison Narcotics Act coincided, as well, with a short-lived effort to prohibit cigarettes. Leaving no stone unturned in the battle to eliminate drugs and alcohol from American life, Henry Ford and Thomas Edison joined forces to wage a public campaign against the “little white slavers.” Edison had shown an earlier fondness for Vin Mariani, a French wine laced with prodigious amounts of cocaine, but he and Ford wanted to stamp out cigarette smoking in the office and the factory. Although that effort would have to wait another 75 years or so, and may yet become the next large-scale test of federal prohibition, New York City did manage to pass an ordinance prohibiting women from smoking in public. Fourteen states eventually enacted various laws prohibiting or restricting cigarettes. By 1927, all such laws had been repealed.

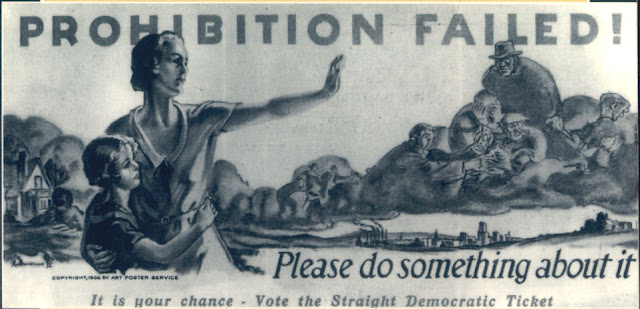

As Prohibition continued, police and federal law enforcement budgets soared, and arrest rates skyrocketed, but no legal maneuvers served to make alcohol prohibition effective, once “respectable” citizens had chosen not to give up drinking. The experience was so repellent that even today, when drug legalization is considered a legitimate topic of debate, most American reformers are unwilling to argue the case for neo-prohibitionism. (America’s ambivalence over alcohol is still evident in some states, where “dry” counties have made the sale of liquor illegal from time to time.)

As the temperance crusaders faded away, politicians and the public turned their attention back to heroin addiction, as the opiates became the official villains again. However, one practice that remained quietly popular with an older generation of physicians well into the 1940s was the conversion of alcoholics into morphine addicts. The advantages of alcohol-to-morphine conversion were spelled out by Lawrence Kolb, the Assistant Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service at the time: “...Drunkards are likely to be benefited in their social relations by becoming addicts. When they give up alcohol and start using opium, they are able to secure the effect for which they are striving without becoming drunk or violent.” Perhaps so, but there were plenty of doctors who did not believe that addiction of any kind fell within the scope of medical practice in the first place.

Subsequent laws tightened up the strictures of the Harrison Act. Mandatory life sentences were imposed in several states for simple possession of heroin. The first addict sentenced to life imprisonment under the new laws was a twenty-one year-old Mexican-American epileptic with an I.Q. of 69, who sold a small amount of heroin to a seventeen year-old informer for the FBI. (In 1962, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that imprisonment for the crime of simply being an addict, in cases where the arrest involved no possession of narcotics, was cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Bill of Rights.)

The Prohibition Years also sparked a rise in marijuana use and marijuana black marketeering. To checkmate the migration toward that drug, Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, modeled closely after the Harrison Act. The American Medical Association opposed this law, as it had opposed the Harrison Act, but to no avail. The assault on marijuana was led by Harry J. Anslinger, the indefatigable U.S. Commissioner of Narcotics who served a Hoover-like stretch from 1930 to 1962. At one point, Anslinger announced that marijuana was being taken by professional musicians. “And I’m not speaking about good musicians,” he clarified, “but the jazz type.” Due in no small part to Anslinger’s tireless public crusade against “reefer madness,” additional state and federal legislation made marijuana penalties as severe as heroin penalties. The most famous early victim of Anslinger’s efforts was screen actor (and reputed jazz fan) Robert Mitchum, who was busted in 1948 and briefly imprisoned on marijuana charges.

One highly addictive drug that did not immediately fall under the proscriptions of the Harrison Act was a cocaine-like stimulant called amphetamine. Originally intended as a prescription drug for upper respiratory ailments and the treatment of narcolepsy (sleeping sickness), the drug was first synthesized in 1887 by a German pharmacologist. It was a British chemist named Gordon Alles, however, who showed everyone just what amphetamine could really do. There was no direct analog in the plant kingdom for this one. Alles, who also worked at UCLA and Caltech, documented the remarkable stimulatory effect of “speed” on the human nervous system—research that led directly to the commercial introduction of amphetamines in the late 1930s under the trade name Benzedrine. Once it became widely available over the counter in the form of Benzedrine inhalers for asthma and allergies, it quickly became one of the nation’s most commonly abused drugs, and remained so throughout the late 1950s and 1960s—with periodic comebacks.

Photo Credit: www.newworldencyclopedia.org

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Last Call: Book Review

Lessons of Prohibition as timely as ever.

It gained serious momentum with the creation of the Anti-Saloon League, the most powerful pressure group in American history. It took down the 5th largest industry in the nation. Financed heavily by teetotaler John D. Rockefeller, it lasted 14 years, and it is mind boggling to contemplate the parallels with the current drug war.

On January 16, 1920, with the official passage of the 18th Amendment banning the manufacture, sale, or transport of alcoholic beverages, America carved out only the second explicit limitation on the activities of its citizens in the Republic’s history. As Daniel Okrent writes in his definitive history, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, “you couldn’t own slaves, and you couldn’t buy alcohol.”

Americans in the late 1800s drank a lot of alcohol. “Multiply the amount American’s drink today by three,” says Okrent. Taxes on whiskey and beer helped pay for the War of 1812 and the Civil War. By the end of the 19th Century, consumption of distilled spirits, particularly whiskey, had been partially replaced by…. beer! It was German immigrant brewers who cornered the market for “liquid bread,” as beer was sometimes known. (Italians who migrated to California sparked Napa Valley’s wine industry.)

Who had the power to take on the brewers and distillers of America in a fight to the finish over alcohol? According to Okrent, the answer was: white Anglo-Saxon protestant women. And not just the well-publicized “hatchetation” of Carrie Nation and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. In fact, the women’s suffrage movement and the drive for prohibition were inextricably linked. The fact of alcohol in family life was one of the reasons women wanted “the right to own property, and to shield their families’ financial security from the profligacy of drunken husbands.” As famed alcoholic Jack London observed, “the moment women get the vote in any community, the first thing they proceed to do is close the saloons.” At least, so London hoped—he thought perhaps prohibition might save his life.

Lamentably, women were joined by racists and nativists in the fight against alcohol and its alleged grip on “the infidel foreign population of our country.” On the Iron Range of northern Minnesota, “congressional investigators counted 256 saloons in fifteen mining towns, their owners representing eighteen distinct immigrant nationalities.” After the United States entered World War I, the Anti-Saloon League stoked anti-German feeling as part of the Prohibition strategy. It was “native-born Protestants against everybody else,” Okrent writes. Demonizing foreigners was and is a useful strategy in any prohibition campaign.

In California, vintners exploited the so-called fruit juice clause in the Volstead Act, the enabling legislation for the 18th amendment. During the California Grape Rush of 1920, “Grapes are so valuable this year that they are being stolen, a Napa Valley newspaper lamented. The fruit juice clause was intended to allow farmer’s wives to “conserve their fruit” by fermenting the apple crop into hard cider.

A second useful loophole for grape growers was an exemption in the Volstead Act, allowing wine use for “sacramental purposes” during Catholic and Jewish ceremonies. A “dry” Methodist dentist promptly responded with a Protestant version: Welch’s Grape Juice.

The third major exception covered the legal distribution of alcoholic beverages “for medicinal purposes”—the only exemption for hard liquor. Clearly, alcohol in its many forms was a necessary part of practicing medicine. But “beverage alcohol” was a different story. Nonetheless, doctors wrote prescriptions for alcohol on government-issued prescription forms, and, despite initial opposition, the American Medical Association (AMA) eventually discovered 27 different medical conditions, ranging from diabetes to old age, which might benefit from the alcohol treatment, arguing that any interference with the medicinal use of liquor would be “a serious interference with the practice of medicine.”

It made for a strange set of bootlegging bedfellows: Rabbis, priests, farmer’s wives, doctors—and Al Capone. Meanwhile, alcohol poured over the border from Canada, came to the coast in ships from the Bahamas, and was offloaded in Seattle from smugglers on land and sea. As one prominent “wet” complained, Prohibition had become “an attempt to enthrone hypocrisy as the dominant force in this country.”

Prohibition even had its own version of “3 Strikes” legislation, called the Jones Law, which imposed up to a five-year sentence for first violations. Lansing, Michigan, passed an ordinance calling for mandatory life in prison for a fourth violation. One effect of such harsh laws was to force out small-time bootleggers, clearing the field for the major operators, like the Bronfman family and its Seagram’s brand of whiskey in Canada.

In the end, as the saying went, “Prohibition was better than no liquor at all.” Yet overall consumption of alcohol did decline, particularly during the early years. Things began to change by the late 1920s, though, as the drys pushed “the limits of law’s ability to defeat appetite.” Part of the problem, Okrent believes, was simple: “Drys didn’t understand drinkers, in scores of different ways.”

“By one accounting, U.S. attorneys across the country spent, at minimum, 44 percent of their time and resources on Prohibition prosecutions—if that was the word for the pallid efforts they were able to sustain on such limited resources,” Okrent writes, again with application to the present state of affairs. In Alabama, prohibition prosecutions accounted for 90 percent of the federal court’s workload. And all this at a time when the federal government had lost more than $440 million in liquor tax revenues, much of which ended up in the pockets of foreign-born criminals. By 1926, bootleg liquor sales were estimated at $3.6 billion nationally, “almost precisely the same as the entire federal budget that year.”

Not a pretty picture. “The business pays very well,” as attorney Clarence Darrow put it, “but it is outside the law and they can’t got to court.” As a result, Darrow said, “they naturally shoot.”

The head of the DuPont family suggested that liquor tax revenues “would be increased sufficiently to warrant the abolition of the income tax and corporation tax,” similar to today’s argument that, by ending drug prohibition, California and other states can balance their precarious budgets.

By the late 1920s, it was said, the only groups who continued to favor Prohibition were evangelical Christians and bootleggers. In 1929, following the Crash and the beginning of the Great Depression, with banks folding and unemployment soaring, “any remaining ability to enforce Prohibition evaporated.” The Repeal movement promised that with the end of Prohibition, the Depression “will fade away like the mists before the noonday sun.” That didn’t happen. But in the first post-repeal year, the government took in more than $250 million in liquor taxes, representing about 9 percent of total federal revenue.

Photo Credit: http://www.druglibrary.org/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)