Showing posts with label alcohol addiction. Show all posts

Showing posts with label alcohol addiction. Show all posts

Sunday, January 7, 2018

Alcohol and Cancer, Explained

"Alcohol and endogenous aldehydes damage chromosomes and mutate stem cells"

Juan I. Garaycoechea, Gerry P. Crossan, Frédéric Langevin, Lee Mulderrig, Sandra Louzada, Fentang Yang, Guillaume Guilbaud, Naomi Park, Sophie Roerink, Serena Nik-Zainal, Michael R.

Stratton & Ketan J. Patel

Nature doi:10.1038/nature25154

This pay-walled article, published in "Nature," presents fresh evidence that alcohol can damage chromosomes and cause mutations. If you don't have a zillion dollars to spare, The American Cancer Society has put together a layman's version of the subject here.

Here's an explainer from Britain's National Health Service. And here's an interview with one of the authors, published in "Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News." Suffice to say that among the many health problems alcohol can cause, the one that all too often goes unmentioned, namely cancer, is not a trivial side effect.

Labels:

alcohol,

alcohol addiction,

alcohol genetics,

alcoholism

Sunday, January 13, 2013

Binge Drinking in America

And the numbers are… fuzzy.

And the numbers are… fuzzy. Public health officials in the UK have been wringing their hands for some time now over perceived rates of binge drinking among the populace. In a 2010 survey of 27,000 Europeans by the official polling agency of the EU, binge drinking in the UK—defined as five or more drinks in one, er, binge—clocked in at a rate of 34%, compared to an EU average of 29%. Predictably, the highest rate of UK binge drinking was found in people between the ages of 15 and 24. This still lagged well behind the Irish (44%) and the Romanians (39%). Scant comfort, perhaps, given the historical role drinking has played in those two cultures, but still, clearly, the British and the rest of the UK are above-average drinkers.

Or are they? And what about the U.S. How do we rank? For comparative purposes, we can use the “Vital Signs” survey in the United States from 2010, performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and published in CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, results of which are pictured above. Using almost the same criteria for binge drinking—five drinks at a sitting for men, four drinks for women—the study concludes that the “overall prevalence of binge drinking was 17.1%. Among binge drinkers, the frequency of binge drinking was 4.4 episodes per month, and the intensity was 7.9 drinks on occasion.”

By the CDC’s definition, the heaviest binge drinking in America takes place in the Midwest, parts of New England, D.C., and Alaska. Survey respondents with an income in excess of $75,000 were the most serious bingers (20.2%), but those making under $25,000 binged more often and had more drinks per binge than other groups, the report says. And binge drinking is about twice as prevalent among men. Binge drinking, the survey concludes, is reported by one of every six U.S. adults.

Even so, it appears that the U.S. does not have the same level of binge drinking as the UK. However, astute readers have no doubt noticed that actual binge drinkers in the U.S. were consuming almost 8 drinks per bout, well above the official mark of four or five drinks at one time. The problem is that there is no internationally agreed upon definition of binge drinking. A 2010 fact sheet from the UK’s Institute of Alcohol Studies (IAS) maintains that “drinking surveys normally define binge drinkers as men consuming at least eight, and women at least six standard units of alcohol in a single day, that is, double the maximum recommended ‘safe limit’ for men and women respectively.”

But referring to binge drinking as “high intake of alcohol in a single drinking occasion” is misleading, says IAS. The problem is biological: “Because of individual variations in, for example, body weight and alcohol tolerance, as well as factors such as speed of consumption, there is not a simple, consistent correlation between the number of units consumed, their resulting blood alcohol level and the subjective effects on the drinker.”

Furthermore, the report charges that “researchers have criticized the term ‘binge drinking’ as unclear, politically charged and therefore, unhelpful in that many (young) people do not identify themselves as binge drinkers because, despite exceeding the number of drinks officially used to define bingeing, they drink at a slow enough pace to avoid getting seriously drunk.”

There you have it. As currently defined and measured, binge drinking is a relatively useless metric for assessing a population’s alcohol habits. “The different definitions employed need to be taken into account in understanding surveys of drinking behavior and calculations of how many binge drinkers there are in the population,” as the UK report wisely puts it. Take the above chart with a few grains of salt.

Photo Credit: CDC

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Last Call: Book Review

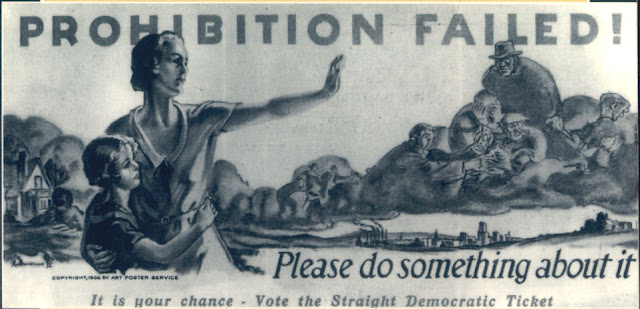

Lessons of Prohibition as timely as ever.

It gained serious momentum with the creation of the Anti-Saloon League, the most powerful pressure group in American history. It took down the 5th largest industry in the nation. Financed heavily by teetotaler John D. Rockefeller, it lasted 14 years, and it is mind boggling to contemplate the parallels with the current drug war.

On January 16, 1920, with the official passage of the 18th Amendment banning the manufacture, sale, or transport of alcoholic beverages, America carved out only the second explicit limitation on the activities of its citizens in the Republic’s history. As Daniel Okrent writes in his definitive history, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, “you couldn’t own slaves, and you couldn’t buy alcohol.”

Americans in the late 1800s drank a lot of alcohol. “Multiply the amount American’s drink today by three,” says Okrent. Taxes on whiskey and beer helped pay for the War of 1812 and the Civil War. By the end of the 19th Century, consumption of distilled spirits, particularly whiskey, had been partially replaced by…. beer! It was German immigrant brewers who cornered the market for “liquid bread,” as beer was sometimes known. (Italians who migrated to California sparked Napa Valley’s wine industry.)

Who had the power to take on the brewers and distillers of America in a fight to the finish over alcohol? According to Okrent, the answer was: white Anglo-Saxon protestant women. And not just the well-publicized “hatchetation” of Carrie Nation and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. In fact, the women’s suffrage movement and the drive for prohibition were inextricably linked. The fact of alcohol in family life was one of the reasons women wanted “the right to own property, and to shield their families’ financial security from the profligacy of drunken husbands.” As famed alcoholic Jack London observed, “the moment women get the vote in any community, the first thing they proceed to do is close the saloons.” At least, so London hoped—he thought perhaps prohibition might save his life.

Lamentably, women were joined by racists and nativists in the fight against alcohol and its alleged grip on “the infidel foreign population of our country.” On the Iron Range of northern Minnesota, “congressional investigators counted 256 saloons in fifteen mining towns, their owners representing eighteen distinct immigrant nationalities.” After the United States entered World War I, the Anti-Saloon League stoked anti-German feeling as part of the Prohibition strategy. It was “native-born Protestants against everybody else,” Okrent writes. Demonizing foreigners was and is a useful strategy in any prohibition campaign.

In California, vintners exploited the so-called fruit juice clause in the Volstead Act, the enabling legislation for the 18th amendment. During the California Grape Rush of 1920, “Grapes are so valuable this year that they are being stolen, a Napa Valley newspaper lamented. The fruit juice clause was intended to allow farmer’s wives to “conserve their fruit” by fermenting the apple crop into hard cider.

A second useful loophole for grape growers was an exemption in the Volstead Act, allowing wine use for “sacramental purposes” during Catholic and Jewish ceremonies. A “dry” Methodist dentist promptly responded with a Protestant version: Welch’s Grape Juice.

The third major exception covered the legal distribution of alcoholic beverages “for medicinal purposes”—the only exemption for hard liquor. Clearly, alcohol in its many forms was a necessary part of practicing medicine. But “beverage alcohol” was a different story. Nonetheless, doctors wrote prescriptions for alcohol on government-issued prescription forms, and, despite initial opposition, the American Medical Association (AMA) eventually discovered 27 different medical conditions, ranging from diabetes to old age, which might benefit from the alcohol treatment, arguing that any interference with the medicinal use of liquor would be “a serious interference with the practice of medicine.”

It made for a strange set of bootlegging bedfellows: Rabbis, priests, farmer’s wives, doctors—and Al Capone. Meanwhile, alcohol poured over the border from Canada, came to the coast in ships from the Bahamas, and was offloaded in Seattle from smugglers on land and sea. As one prominent “wet” complained, Prohibition had become “an attempt to enthrone hypocrisy as the dominant force in this country.”

Prohibition even had its own version of “3 Strikes” legislation, called the Jones Law, which imposed up to a five-year sentence for first violations. Lansing, Michigan, passed an ordinance calling for mandatory life in prison for a fourth violation. One effect of such harsh laws was to force out small-time bootleggers, clearing the field for the major operators, like the Bronfman family and its Seagram’s brand of whiskey in Canada.

In the end, as the saying went, “Prohibition was better than no liquor at all.” Yet overall consumption of alcohol did decline, particularly during the early years. Things began to change by the late 1920s, though, as the drys pushed “the limits of law’s ability to defeat appetite.” Part of the problem, Okrent believes, was simple: “Drys didn’t understand drinkers, in scores of different ways.”

“By one accounting, U.S. attorneys across the country spent, at minimum, 44 percent of their time and resources on Prohibition prosecutions—if that was the word for the pallid efforts they were able to sustain on such limited resources,” Okrent writes, again with application to the present state of affairs. In Alabama, prohibition prosecutions accounted for 90 percent of the federal court’s workload. And all this at a time when the federal government had lost more than $440 million in liquor tax revenues, much of which ended up in the pockets of foreign-born criminals. By 1926, bootleg liquor sales were estimated at $3.6 billion nationally, “almost precisely the same as the entire federal budget that year.”

Not a pretty picture. “The business pays very well,” as attorney Clarence Darrow put it, “but it is outside the law and they can’t got to court.” As a result, Darrow said, “they naturally shoot.”

The head of the DuPont family suggested that liquor tax revenues “would be increased sufficiently to warrant the abolition of the income tax and corporation tax,” similar to today’s argument that, by ending drug prohibition, California and other states can balance their precarious budgets.

By the late 1920s, it was said, the only groups who continued to favor Prohibition were evangelical Christians and bootleggers. In 1929, following the Crash and the beginning of the Great Depression, with banks folding and unemployment soaring, “any remaining ability to enforce Prohibition evaporated.” The Repeal movement promised that with the end of Prohibition, the Depression “will fade away like the mists before the noonday sun.” That didn’t happen. But in the first post-repeal year, the government took in more than $250 million in liquor taxes, representing about 9 percent of total federal revenue.

Photo Credit: http://www.druglibrary.org/

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

What Type of Drinker Are You?

U.K health officials classify problem drinkers.

In an effort to combat problem drinking with “social marketing techniques,” the British Department of Health has released a study purporting to break down heavy drinkers into 9 distinct personality types, according to the U.K. Guardian.

British Department of Health researchers performed the studies at the behest of the National Health Service, which says that alcohol-related illnesses cost England almost $5 billion each year. It was unclear what criteria were used to identify and define the nine types.

BBC news quoted Health Minister Dawn Primarolo on the findings: "This will be a tough one to crack. Research found many positive associations with alcohol among the general public - even more so among those drinking at higher-risk levels. For these people alcohol is embedded in their identity and lifestyle: so much so that challenging this behaviour results in high levels of defensiveness, rejection or even outright denial."

The idea behind the investigation is to identify the social and psychological characteristics of problem drinkers “in an attempt to devise more effective public health campaigns to encourage safer use of alcohol.”

THE NINE TYPES OF DRINKER

1) Depressed drinker:

Life in a state of crisis. Alcohol as self-medication, comforter. Any sex, all age groups.

2) De-stress drinker:

Stressful job and/or home life. Alcohol as relaxation, dividing line between work and personal life. Middle class men and women.

3) Re-bonding drinker:

People with a crammed calendar. Alcohol as “shared connector,” a means of keeping close to others.

4) Conformist drinker:

Traditonalist drinker. Alcohol as “me time,” the pub as second home, a sense of belonging. Typically middle-aged men in blue-collar or clerical jobs.

5) Community drinker:

Alcohol as social network, a sense of safety and security. Lower middle class men and women who drink in large social groups.

6) Boredom drinker:

Alcohol as stimulation, comfort in isolation. Often single moms or recent divorcees.

7) Macho drinker:

Alpha males, drinking as an assertion of masculinity, alcohol as a competition.

8) Hedonistic drinker:

Excessive drinking as an assertion of independence, freedom, release from inhibitions. Often single or divorced men or women, or older drinkers with grown children.

9) Border dependents:

Alcohol as a defense against the need to conform, and a general sense of malaise. Typically men for whom the pub is “home.”

The research was done as part of a renewed effort to to crack down on heavy drinkers. A pilot program will be undertaken over the coming months to target heavy drinkers. More than 900,000 households will be mailed information highlighting the link between drinking and conditions such as cancer and liver disease.

photo credit: http://www.ulv.edu

Labels:

alcohol addiction,

alcoholism,

heavy drinking,

problem drinker,

pub

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Take the Alcohol Test

CAGE questionnaire still a useful tool

Despite the time, labor, and expense that have gone into the search for a better way to diagnose alcoholism, researchers have yet to outdo what may be the simplest, most accurate test for alcoholism yet devised. A set of four simple, relatively non-controversial questions, first devised in 1970 by Dr. John A. Ewing, still serve as a useful predictive tool for alcoholism.

Neurobiology has taught us that addictive drugs cause long-lasting neural changes in the brain. The problems start when sustained, heavy drinking forces the brain to accept the altered levels of neurotransmission as the normal state of affairs. As the brain struggles to adapt to the artificial surges, it becomes more sensitized to these substances. It may grow more receptors at one site, less at another. It may cut back on the natural production of these neurotransmitters altogether, in an effort to make the best of an abnormal situation. In effect, the brain is forced to treat alcoholic drinking as normal, because that is what the drinking has become.

The likelihood that many alcoholics and other drug addicts have inherited a defect in the production and distribution of serotonin and other neurotransmitters is a far-reaching finding. While it is difficult to measure neurotransmitter levels directly in brains, there are indirect ways of doing so. One such method is to measure serotonin’s principle metabolic breakdown product, a substance called 5-HIAA, in cerebrospinal fluid. From these measurements, scientists can make extrapolations about serotonin levels in the central nervous system as a whole.

However, testing for serotonin levels is imprecise and impractical in the real world of the doctor's office and the health clinic. Despite all the promising research on neurotransmission, what can physicians and health professionals do today to identify alcoholics and attempt to help them? For starters, physicians could look beyond liver damage to the many observable “tells” that are characteristic patterns of chronic alcoholism—such manifestations as constant abdominal pain, frequent nausea and vomiting, numbness or tingling in the legs, cigarette burns between the index and middle finger, jerky eye movements, and a chronically flushed or puffy face. Such signs of acute alcoholism are not always present, of course. Many practicing alcoholics are successful in their work, physically healthy, don’t smoke, and came from happy homes.

The CAGE test takes less than a minute, requires only paper and pencil, and can be graded by test takers themselves. It goes like this:

1. Have you ever felt the need to (C)ut down on your drinking?

2. Have you ever felt (A)nnoyed by someone criticizing your drinking?

3. Have you ever felt (G)uilty about your drinking?

4. Have you ever felt the need for a drink at the beginning of the day—an “(E)ye opener?

People who answer “yes” to two or more of these questions should seriously consider whether they are drinking in an alcoholic or abusive manner.

--Excerpted from The Chemical Carousel: What Science Tells Us About Beating Addiction © Dirk Hanson 2008, 2009.

Monday, October 29, 2007

Profiles in Addiction Science

Henri Begleiter and the P3 wave

At the State University of New York’s Health Science Center in Brooklyn, the late Dr. Henri Begleiter, a professor of psychiatry, began investigating the brain wave activity of alcoholics in the early 1980s. According to Dr. Ting-Kai Li, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA):

“Starting with the ground-breaking finding, published in Science, that some neurophysiological anomalies in alcoholics were already present in their young offspring before any exposure to alcohol and drugs, he proposed a model that changed the thinking in the field: namely, rather than a consequence of alcoholism, this neural hyperexcitability was a predisposing factor leading to the development of alcoholism and related disorders. This innovative study was replicated throughout the world and launched him on a systematic search to elucidate the genes underlying this predisposition.”

People have heard of alpha waves and theta waves, but there are many other brain waves, evoked by various kinds of stimulation. Scientists can now measure electrical phenomena called evoked potentials (EPs), and event-related potentials (ERPs). For example, certain characteristic waveforms occur when the brain reacts to visual and auditory stimuli--when a person sees flashes of light, for example, or hears a clicking noise. As the signal of the flashing light makes its way from the retina of the eye to the cortex of the brain, electrodes placed on the scalp record the nerve impulses.

Begleiter and his coworkers recorded various event-related potentials, using scalp electrodes. The result was a series of sine wave-like printouts measuring amplitude and elapsed time for any given brain wave. The so-called P3 voltage, a measure of reaction time invoked by such stimuli as flashing lights or clicking noises, especially interested the researchers. Prior testing had shown that people suffering from schizophrenia or attention deficit disorder exhibited low P3 amplitudes. When Begleiter’s team tried recording P3 waves, something odd turned up. Diminished P3 waves were characteristic of an overwhelming majority of practicing alcoholics. As it turned out, the same event-related P3 wave abnormalities could be found in recovering alcoholics--even when they had been abstinent for years.

It was left for Begleiter’s team to round up a group of children ranging in age from six to eighteen, all of whom had an alcoholic parent, and all of whom, as Begleiter’s team documented, showed the same diminished amplitude in P3 waves. None of the children had ever been exposed to alcohol before. Nonetheless, there it was: The P3 waves of these children exhibited exactly the same waveform abnormalities as their actively alcoholic parents.

When Begleiter limited the pool of brain scan volunteers to the sons of fathers who had been diagnosed as Type 2 alcoholics, and compared their P3 waves with the P3 waves of a control group, he was able to correctly identify the children of Type 2 fathers almost 90 per cent of the time. Begleiter had discovered an organic impairment in the brains of non-drinking siblings of alcoholics.

Begleiter’s work caught most genetic researchers by surprise. Numerous laboratories raced to replicate Begleiter’s findings--and consistently succeeded. The P3 deficit was verifiable, and repeatable. Addiction researchers sat up and took notice: Here was compelling evidence of a marker for alcoholism; a specific abnormality in the brain which was apparently passed on genetically in alcoholic families.

“Actually, it’s more than just the P3,” Begleiter told me at the time. A colleague of Begleiter’s, neuroscientist Bernice Porjesz, found that an additional neurological oscillation, the N400 waveform, was markedly different in the children and families of alcoholics. The children with abnormal P3 or N400 waves were more likely to abuse drugs and tobacco in later years. The P3 findings have been thoroughly verified in other laboratories all over the country. There have been no retractions, and little difficulty in duplicating the findings. Begleiter’s markers are solid.

Friday, October 12, 2007

Topamax for Alcoholism: A Closer Look

Epilepsy drug gains ground, draws fire as newest anti-craving pill

A drug for seizure disorders and migraines continues to show promise as an anti-craving drug for alcoholism, the third leading cause of death in America, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) reported in its current issue.

371 male and female alcoholics between the ages of 18 and 65 took part in the study. The subjects received either topiramate or a placebo. Over 14 weeks, patients taking topiramate showed a significantly higher rate of abstinence for 28 consecutive days or more. (Rates of abstinence increased slightly in the placebo group as well. Both groups received some psychological counseling.)

Topamax is currently only approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use against seizures and migraine. The controversial practice of “off-label” prescribing—using a drug for indications that are not formally approved by the FDA—has become so common that Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) said it had no plans to seek formal approval for the use of Topamax as a medicine for addiction.

In an editorial accompanying the study, published in the October 10 issue of JAMA, Mark Willenbring of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) wrote: “We now have very high-quality evidence that shows efficacy. The medical world doesn’t wait for the indication. Topamax is a drug that many physicians have used and many patients have had an experience with because of its use in migraines.”

In addition, Topamax is already prescribed off-label in some cases for depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, according to reports.

At present, there four medications legally available by prescription for alcoholism: disulfiram (Antabuse), SSRIs (off-label), naltrexone (Revia and Vivitrol), and acamprosate, the latest FDA-approved entry. Acamprosate binds to both GABA and glutamate receptors. Acamprosate, marketed in the U.S. as Campral, has been widely used in Europe on problem drinkers.

Dr. Bankole Johnson, chairman of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia, told Bloomberg News that Topamax does everything researchers want to see in a pharmaceutical treatment for alcoholism: “First, it reduces your craving for alcohol; second, it reduces the amount of withdrawal symptoms you get when you start reducing alcohol; and third, it reduces the potential for you to relapse after you go down to a low level of drinking or zero drinking.”

According to Forbes.com, “The drug isn’t cheap—it costs about $1,000 for three months, according to Johnson. “And, patients, don’t see benefits for two to four weeks.”

Moreover, Topiramate is not without serious side effects for some users, including vision problems, difficulty remembering words, and a tingling in the arms and legs known as parasthesia.

The study was funded by Ortho-McNeil-Janssen, the subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson that produces and markets Topamax. Citing this and other alleged irregularities, Public Citizen’s Sidney Wolfe, Director of the Health Research Group, sent a stinging letter to the FDA demanding that the agency “stop the illegal and dangerous promotional campaign by Ortho-McNeil-Janssen-funded researchers for the unapproved use of Topamax (topiramate) for treating alcoholics.”

And to make things even more interesting, drug developer Mylan (MYL) received FDA approval last month for a generic form of Topamax, seeking a share of the estimated $50 million in annual sales the drug currently enjoys.

Like Campral, Topamax causes changes in the GABA and glutamate systems, which in turn affect dopamine and serotonin function. Acamprosate, like topiramate, harkens back to earlier work on GABA transmission in alcoholism. Both drugs attack the craving and relapse dilemma by stimulating GABA, the inhibitory transmitter that is the target of benzodiazepines like Valium, Xanax and Klonopin. However, Campral is not sedating. There is no buzz, no psychoactive effect, and no evidence of abuse potential whatsoever. Major side effects of acamprosate include gastrointestinal cramps and diarrhea. In addition, Campral may also “restore receptor tone” in the hyperactivated glutamate system of the alcoholic, specifically in the nucleus accumbens.

In a dozen clinical trials conducted in Europe, involving thousands of alcohol abusers, 50 per cent of acamprosate users maintained sobriety for three months without relapse, compared to 39 per cent of the placebo group. (The distressingly low numbers are testimony to the fierce mechanism of relapse.)

Topamax shows a similar mechanism of action. Earlier, researchers from the University of Texas conducted topiramate studies at the South Texas Addiction Research and Technology Center, later published in Lancet. Alcoholic patients achieved a rate of continuous abstinence six times higher than those in a placebo group did. They also reported fewer cravings, compared to a placebo group.

The downside to Topiramate may prove to be side effects. The NIAAA’s Raye Z. Litten, chief of treatment research, believes that the drug may ultimately be a strong player. “On the other hand,” he cautions, “Topiramate appears to have more severe side-effects than naltrexone and acamprosate.” Litten argues that greater efforts at testing are needed.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) estimated that it would be sponsoring more than 30 new clinical trials of drugs for alcoholism in the next few years. The JAMA editorial, “Medications to Treat Alcohol Dependence,” concludes that the pace of development for alcoholism drugs in increasing. “A solid understanding of the neurobiology of alcohol addiction is providing the framework for multiple avenues of further medication development.”

Labels:

alcohol addiction,

alcoholism,

drug treatment,

topamax,

topiramate

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)