Showing posts with label marijuana. Show all posts

Showing posts with label marijuana. Show all posts

Friday, July 15, 2011

There’s No Agreement on DUIC: Driving Under the Influence of Cannabis

The ACLU squares off against law enforcement over how to measure marijuana impairment.

What’s your blood cannabis content? You don’t know, and neither does anybody else, without a fair bit of effort. There’s no device to blow into, no quick chemical field test. You’re impaired by marijuana if the officer says you’re impaired by marijuana, and in most states he or she will decide that matter by using a series of sobriety checks not dissimilar to the well-known alcohol exercises: standing on one foot, walking a line, having your eyeballs and blood pressure checked—and my personal favorite, a test of how well you can guess when 30 seconds is up. Time passes more slowly when you’re about to be arrested for drugs, I’m guessing, since it takes a little while for your life to pass before your eyes. Even the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration admits that it is “difficult to establish a relationship between a person's THC blood or plasma concentration and performance impairing effects. Concentrations of parent drug and metabolite are very dependent on pattern of use as well as dose."

The point is, observable indications of impairment, as they’re called, are really all that law enforcement currently has as a tool for policing the use by drivers of American’s second most popular drug. At one extreme end of the spectrum are the pot enthusiasts who argue that no amount of marijuana significantly impairs you behind the wheel. At the other end of the spectrum stand the zero-tolerance advocates: No amount of marijuana is safe, if you’re planning to get behind the wheel within the next several hours—or at any time during the rest of your life, as some anti-drug advocates seem to be saying.

And somewhere in between, according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Washington State, lies a possible compromise for gauging marijuana impairment. “Adding a science-based threshold for likely impairment to the mix and providing educational information that allows people to estimate their personal level of intoxication can be effective strategies for preventing impaired driving in the first place and improving public safety,” the ACLU asserts.

The ACLU favors the so-called Pennsylvania Model, which sets that state’s legal limit for cannabis in whole blood at 5 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). Why 5, and not some other number? Because a legal cut-off of 5 ng/mL is also what the National Organizaton for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) recommends, based in turn on an analysis of scientific studies of marijuana’s effect on driving skills. Specifically, NORML recommends a limit in the range of 3.5-5.0 ng/mL, which the group says will “clearly separate unimpaired drivers with residual THC concentrations of 0-2 ng/mL from drivers who consumed cannabis within the last hour or so.” Levels under that range tend to indicate that the driver smoked at least 1 to 3 hours ago. Anyone testing over that range, says NORML is “likely to be impaired.”

But it’s not quite that simple, of course. First, you have to rule out a whole roster of cannabis metabolites that stay in the system for days or weeks, but have no impact on driving skills. And the metabolism of cannabinoid by-products varies so widely from person to person (this is just beginning to be understood scientifically), that the results of testing are not foolproof. The iron law of metabolic diversity makes that claim unlikely. Moreover, there is currently no reliable way of testing blood in the field for THC concentrations. But there will be. Introducing the Vantix Biosensor, a device that looks, ironically, like a portable vaporizer for marijuana. Open your mouth, please, as the officer politely swabs the inside of your cheek with a plastic wand, and inserts the wand in the handheld machine. Sensors on a microchip react with telltale antibodies, and you test positive for cocaine, or marijuana, or, soon, synthetic marijuana. Or perhaps it will be some other company’s device. But rest assured it is being looked upon as a growth market.

And then there is, as the ACLU points out, the wrong way to go about it: zero tolerance. At least 11 states have now set the requisite cut-off level for illegal drugs at zero. That may raise a cheer in certain quarters of the anti-drug movement, but it is a decision “based not in science but on convenience,” says the ACLU. It establishes a crime wholly “divorced from impairment” behind the wheel. Put simply, zero tolerance “does not differentiate between a dangerously incapacitated driver and an individual who may have smoked the past Monday but was pulled over as a sober ‘designated driver’ on Saturday night.” Furthermore, “even a statute excluding cannabis metabolites but criminalizing trace amounts of THC” could result in the arrest of drivers several days after they last smoked pot. It’s pretty simple, really. “If science dictates that the presence of a trace amount of cannabis or a cannabis metabolite in an individual’s blood has NO ‘influence’ on his capacity to drive, it should not constitute per se evidence of ‘driving under the influence.’” But toxicologist Marilyn Huestis, at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, disagrees. She believes that there is no safe level of marijuana consumption, where driving is concerned. Paul Armentano, deputy director for NORML, scoffs at that, telling the Los Angeles Times that individual states “are not setting a standard based on impairment, but one similar to saying that if you have one sip of alcohol you are too drunk to drive for the next week.”

One abiding problem is that for car accidents, it’s not necessarily a pure play. Alcohol mixed with one or more additional drugs is common, and if it’s difficult to set limits for alcohol and marijuana alone, imagine the permutations involved in creating legal limits for a combination of both. A 2007 survey of experimental studies, published in Addiction by a group of researchers in six countries, concluded that a rule of thumb police might want to consider is based on the finding that “a THC concentration in the serum of 7–10 ng/ml is correlated with an impairment comparable to that caused by a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.05%. Thus, a suitable numerical limit for THC in serum may fall in that range.” Considering that we allow drivers to exhibit blood alcohol limits as high as 0.08, NORML’s 5 ng/mL limit looks downright conservative.

There’s no simple solution. Maybe that’s because cannabis is not a simple drug. We’re still teasing apart its effects, and nailing down the particulars of driving under the influence of cannabis is one of them. As Jeffrey P. Michael of the National Highway Traffic Safety Adminstration refreshingly disclosed to the Los Angeles Times, “We don’t know what level of marijuana impairs a driver.” But they are trying to find out. A federal study in Virginia intends to round up more than 7,000 blood samples by showing up at the scene of car accidents and asking drivers to provide random, anonymous samples to compare with control samples.

Other studies of a similar nature are underway. Driving under the influence of drugs could become as common a criminal charge as classic DUIs and DWIs.

Photo credit: http://www.janisian.com/

Labels:

California pot laws,

cannabis,

driving under the influence,

DUI,

DUIC,

marijuana

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

Drug Czar Kerlikowske Interviewed in Foreign Policy Magazine

Drug War goes international in a big way.

Gil Kerlikowske, Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy--a.k.a. the Drug Czar--finds himself in a curious position. Kerlikowske can be forgiven for feeling a little like J. Edgar Hoover, when the FBI director found that domestic security at home seemed to require some rather active investigations into Cubans and other Communists abroad. Kerlikowske is now riding a horse he never had much say in buying. The U.S. is in the midst of launching a new international drug strategy consisting of “interlocking plans” in Central and South America aimed at “transnational criminal groups.”

AFP reporter Jordi Zamora wrote that “the strategy will merge a handful of existing programs, including Plan Colombia, which has received more than $6 billion in U.S. aid since it was launched in 2000, and the Merida Initiative for Mexico, for which Congress has appropriated $1.5 billion since 2008.” Kerlikowske said that the global nature of the drug threat “requires a strategic response that is also global in scope.” With various crackdowns and battles over smuggling routes, the drug trade in the region has led to thousands of deaths, and has created “complex and evolving threats” from crime syndicates,” according to Assistant Secretary of State William Brownfield. However, “progress in Central America will only push drug traffickers elsewhere if we do not support strong institutions throughout the hemisphere,” he said. It seems like the Office of National Drug Control Policy continues to be internationalist in scope.

With all that as background, Foreign Policy magazine spoke with Kerlikowske in search of more detail, and got some--including a strange paean to America’s ability to produce and distribute its own illegal drugs, with no help from Mexico, thank you very much. Kerlikowske seems almost to be bragging. And if he’s right, what are all those border killings about, anyway?

FP: What's your big-picture sense of the drug situation in Latin America?

GK: It used to be fairly easy to categorize countries as production countries, transit countries, or consumer countries. I think those lines have been--if not completely obliterated--generally blurred. The amount of drug use in Mexico is significant. It's also clear from my most recent trip to visit drug treatment centers in Colombia that they're concerned as well.

FP: U.S. Ambassador Carlos Pascual was forced to leave his position in Mexico two weeks ago because of comments he made in WikiLeaks cables about the perception that the drug war in Mexico is failing and about pervasive corruption in Mexican law enforcement. Are those concerns you share?

GK: As a police officer, I can say that cynicism just comes with the territory, and it's pretty easy to adapt that kind of attitude to Mexico. I'm not overly optimistic, but I think there has been some progress and we have an administration that's courageously taking on these criminal organizations, who are now involved in so many other kinds of crimes.

FP: It does seem that there have been a number of recent scandals involving U.S.-Mexico drug partnership: the Pascual resignation, the reports of the ATF allowing cross-border gunrunning, the controversial use of drones over Mexican territory. Has that relationship become more difficult lately?

GK: In my two years of dealing with this on a closer level, I'd say these last two months are more strained than during the rest of the time I've been here, but I don't see it as a significant bump in the road or a glitch that's going to stop things.

FP: What do you say to those in Latin America who say that it’s useless to crack down on the drug trade as long as the demand persists from the United States?

GK: For one thing, we've become much better at producing drugs in the United States: hydroponic marijuana with a very high THC content -- public lands produce a lot of marijuana. And we don't get any prescription drugs smuggled in to any great extent--which, right now, are our No. 1 growing drug problem in the United States, and also methamphetamine. We're getting much better at making our own, albeit in small amounts.

FP: How do you respond to the growing number of former Latin American leaders--former Mexican President Vicente Fox, most recently--who have come out in favor of legalization or at least a radical overhaul of the current policy?

GK: Isn't it funny how people who no longer have responsibility for anyone's safety or security suddenly see the light? I think it's not a lot different from what we've heard in recent years in the United States, which is: We've had a war on drugs for 40 years and we don't see success. If we have a kid in high school, they can still get drugs or there's drugs on the street corner. So legalization must be an answer…. Heaven knows, we're not very successful with alcohol. We don't collect much in tax money to cover the costs. We certainly can't keep it out of the hands of teenagers or people who get behind the wheel. Why in heaven’s name do we think that if we legalize marijuana, we'd have a system where we could collect enough tax revenue to cover the increased health-care costs? I haven't seen that grand plan. “

Photo Credit: www.fs.fed.us

Labels:

drug czar,

drug policy,

drug war,

Kerlikowske,

marijuana

Thursday, April 7, 2011

Marijuana, Vomiting, and Hot Baths

A case history of cannabinoid hyperemesis.

Cannabinoid hyperemesis, as it's known, is an extremely rare but terrifying disorder marked by severe episodic vomiting that can only be relieved by hot baths. (see earlier post). Sufferers are heavy, regular cannabis users, most of them. And hot baths? Where did THAT come from?

The syndrome was first brought to wider attention last year by the anonymous biomedical researcher who calls himself Drugmonkey, who documented cases of hyperemesis that had been reported in Australia and New Zealand, as well as Omaha and Boston in the U.S. "There were two striking similarities across all these cases," Drugmonkey reported. "The first is that patients had discovered on their own that taking a hot bath or shower alleviated their symptoms. So afflicted individuals were taking multiple hot showers or baths per day to obtain symptom relief. The second similarity is, as you will have guessed, they were all cannabis users."

The reports haven't stopped. This summer, an intriguing account appeared on the official blog of New York University's Division of General Internal Medicine, where med students offered a formal definition: "A clinical syndrome characterized by intractable vomiting and abdominal pain associated with the unusual learned behavior of compulsive hot water bathing, occurring in the setting of long-term heavy marijuana use."

Still skeptical? I received this heartfelt comment on my original post a few days ago:

Listen, doubters. My son has this. He has been cyclical vomiting and spending hours in boiling hot baths since last Autumn. It's getting worse and he has lost a hell of a lot of weight. He is 21 and an addicted, heavy cannabis user who started at 15. He has tried cutting down but every other joint of weed brings on the obsession. He refuses to co operate with medical staff who try to treat him.

He has been taken to numerous hospitals as an emergency for non-stop vomiting and begs medical staff to let him sit in a very hot bath. They try the best anti-vomiting drugs instead, to no effect, and then some let him go in a hot shower for an hour plus. He always ends up on a drip and as soon as he feels well enough, discharges himself, often the same day.

At the weekend he went to a sports event in the city with friends, realised on the way he was going to have an episode, so left friends and made his way into a hotel room and locked himself in. Police were called and got him out of a boiling hot bath against his will. Cue vomiting attack so bad police called an ambulance. Once again discharged himself from hospital, demanding drip be removed or he would do it himself. Has sat in bath at house he shares with girlfriend for at least 12 hours today, she tells me. She says water is so hot she has no idea how he bears it.

He says he has no pain in stomach, just a sensation that drives his head mad and he KNOWS it will not go, or the vomiting stop, until he gets in boiling hot bath and stays there. He has even done this while abroad on holiday and ended up on a drip before being flown home.

All of this is true. A mother.

I was intrigued, and discussed this briefly with the mother, who lives in the U.K. She added a number of details in an email exchange, and agreed to let me publish her comments:

“I am a mother in the UK whose son definitely has this, but is not officially diagnosed as he ‘escapes’ medical attention by discharging himself from various hospitals.

When it happens he is desperate to get in a hot bath. He lives with his girlfriend. I only realised what the hell was really going on when she insisted on telling me, and have since been regularly involved in the hospitals saga.

When I discovered the truth I put ‘cannabis’ ‘vomiting’ and ‘hot baths’ ‘showers’ in google and up came a perfect description of what my son does.

I am trying to get him to agree to go for counselling and psychiatric help as he has reached the stage where this obsessive vomiting and bathing is wrecking his life. But every time he gets a little better he believes he can ‘control it’ which is not the case at all.

Yes – we end up in the hospitals and the first young emergency doctor who has ever smoked a joint and/or thinks he knows everything, tells G “Oh no it can’t be that, cannabis stops vomiting, not starts it.” Of course, they have never heard of this condition and just think he is being irrational because of the constant need to vomit. They are sure it is food poisoning or some kind of spasm and take basic blood tests.

They find nothing, insist on giving him the best anti-sickness drugs usually for cancer patients and so on…, saying “this will definitely stop it” and still he vomits. He is not in pain, just rapidly dehydrating and panicking and complaining of a weird sensation in his stomach. He tells them “I know it’s in my head doing this” and desperately demands to get in a bath. Even when he has arrived at hospital because police found him in a boiling hot bath, this makes no sense to the medics who only give in when none of their drugs work. He then immediately stops vomiting but is petrified of getting out of the bath. Eventually, when he says it is under control, he agrees to get out, and is put on a drip. Approx an hour later, while the doctors are planning follow-up procedures like scans and more complex blood tests etc, he starts an argument with a nurse, insists the drip is removed and phones a friend to collect him, avoiding seeking a lift from me if he can. The over-pressed doctors here (the British system is like a cattle market) are left mystified and move onto the next emergency in their pile up of admissions. And so it goes on, and will do, until G accepts even the odd joint can set him off.”

----

Researchers speculate that it has something to do with CB-1 cannabinoid receptors in the intestinal nerve plexus--but nobody really knows for sure. Low doses of THC might be anti-emetic, whereas in certain people, the high concentrations produced by long-term use could have the opposite effect.

Wednesday, March 2, 2011

Spice, K2, Other “Fake Pot” Illegal as of March 1

DEA makes synthetic marijuana a Schedule 1 drug.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) exercised its emergency scheduling authority yesterday to outlaw the use of “fake pot” products.

Sixteen states have already passed a mishmash of legislation outlawing one or more of the drugs in question, which are typically sold as Spice, K2 or Red X.

The DEA had already announced its intention to put 5 new drugs--JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-200, CP-47, 497, and cannabicyclohexanol--on the official list of scheduled substances. “These products consist of plant material that has been coated with research chemicals that claim to mimic THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, and are sold at a variety of retail outlets, in head shops, and over the Internet,” the DEA said in a prepared statement. “The temporary scheduling action will remain in effect for at least one year while the DEA and the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) further study whether these chemicals should be permanently controlled."

According to the DEA, “Emergency room physicians report that individuals that use these types of products experience serious side effects which include: convulsions, anxiety attacks, dangerously elevated heart rates, increased blood pressure, vomiting, and disorientation.”

The smokable herbal products were designated as Schedule 1 substances, the federal government’s most restrictive category, ostensibly reserved for drugs with “no accepted medical use for treatment in the United States and a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug under medical supervision.” Marijuana is also a Schedule 1 drug, along with heroin, Ecstasy, and LSD. The supposedly less dangerous Schedule 2 drugs, bizarrely, contain the most problematic drugs of all in terms of human health and addictive potential: methamphetamine, oxycontin, and cocaine. Schedule 3 is so confusing as to defy coherent description, while Schedule 4 is the valium category and Schedule 5 is the Robitusson category.

One problem with the whack-a-mole approach to drug enforcement is that developers of designer drugs can easily stay one jump ahead of the law. What many drug officials and agencies, including the International Narcotics Control Board, want to see is sweeping, generic bans on whole categories of chemicals, in order to win the game of leapfrog.

However, as reported by Maia Szalavitz at Time Healthland, broad-spectrum drug bans “could have the unintended effect of keeping potential cures for diseases like Alzheimer’s out of the pharmaceutical pipeline.” As Szalavitz notes, “getting a drug out of Schedule 1 is much harder than getting it into that legal category, as supporters of medical marijuana and MDMA have discovered.”

And if clinical researchers wish, say, to pursue JWH-133--a chemical compound closely related to the newly banned drugs—for its ability to reduce the inflammation associated with plaque buildup in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, they are going to find that research almost impossible to do, as more and more chemicals escape the lab or emerge from the work of underground chemists and ultimately become illegal substances.

Notice of Intent to Temporarily Control Five Synthetic Cannabinoids

Graphics Credit: http://newsbythesecond.com/

Labels:

DEA bans spice,

fake pot,

k2,

marijuana,

Schedule 1 Drugs,

spice

Monday, December 6, 2010

Cannabis and Severe Vomiting

For those of you who missed this, as I did, here is a belated account of a rare but altogether curious side effect of heavy marijuana use: cyclical vomiting.

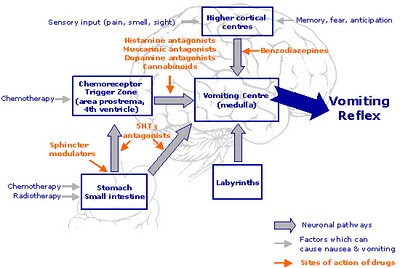

Nice, eh? And yes, it goes completely against the grain of what we think we know about marijuana: Ironically, cannabis is frequently employed to prevent the nausea and vomiting frequently associated with chemotherapy.

So what gives? The answer is that, so far, nobody really knows.

First things first: It appears to be a very rare side effect of regular marijuana use, and it was not documented in the medical literature until 2004. Given the long history of pot-smoking the world over, it is reasonable to ask where the cannabis emesis syndrome has been hiding all these years. A fair question, but one which, at this stage, has no satisfying answer.

Cannabinoid hyperemesis, as it's known, was first brought to wider attention earlier this year by the anonymous biomedical researcher who calls himself Drugmonkey. Posting on his eponymous blog, Drugmonkey documented cases of hyperemesis that had been reported in Australia and New Zealand, as well as Omaha and Boston in the U.S.

"There were two striking similarities across all these cases," Drugmonkey reported. "The first is that patients had discovered on their own that taking a hot bath or shower alleviated their symptoms. So afflicted individuals were taking multiple hot showers or baths per day to obtain symptom relief. The second similarity is, as you will have guessed, they were all cannabis users."

Heavy, regular cannabis users, most of them. And hot baths? Where did THAT come from?

More evidence was not long in coming. In February, researchers in the Division of Gastroenterology at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan, identified eight patients in their gastroenterology wards who were suffering from "otherwise unexplained refractory, recurrent vomiting." As the researchers reported in the journal Digestive Diseases and Sciences, there were two other significant features the eight patients shared: They were all chronic cannabis smokers--and they were all compulsive bathers.

The connection between uncontrolled vomiting and heavy toking seemed unequivocal: "Four out of five patients who discontinued cannabis use recovered from the syndrome," according to the published report, "while the other three patients who continued cannabis use, despite recommendations for cessation, continued to have this syndrome."

There is precious little anecdotal evidence to support this surprising finding. Occasionally, naive marijuana smokers will ingest too much and become sick to their stomach. And it is possible to incur the (brief) wrath of cyclic vomiting by eating way too many marijuana brownies, or other cannabis foodstuffs. Short of that, I am not familiar with vomiting as a documented side effect of regular cannabis use, and I venture to guess that most readers aren't, either.

However, the reports haven't stopped. This summer, an intriguing account appeared in Clinical Correlations, the official blog of New York University's Division of General Internal Medicine. Sarah A. Buckley and Nicholas M. Mark, 4th year medical students at the NYU School of Medicine, speculated on the cannabis hyperemesis phenomenon, and offered a formal definition: "A clinical syndrome characterized by intractable vomiting and abdominal pain associated with the unusual learned behavior of compulsive hot water bathing, occurring in the setting of long-term heavy marijuana use."

After reviewing 16 published papers on the syndrome, Buckley and Mark asked the obvious question: "How can marijuana, which is used in cancer clinics as an anti-emetic, cause intractable vomiting? And why would symptoms abate in response to high temperature?"

One possible mechanism involves marijuana's penchant for fats. Theoretically, this "lipophilicity" could cause increasingly toxic concentrations of THC over time, in susceptible people. "The abdominal pain and vomiting are explained by the effect of cannabinoids on CB-1 receptors in the intestinal nerve plexus," they write, "causing relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and inhibition of gastrointestinal motility." The authors speculate that low doses of THC might be anti-emetic, whereas in certain people, the high concentrations produced by long-term use could have the opposite effect.

As for the hot baths, Buckley and Mark note that "cannabis disrupts autonomic and thermoregulatory functions of the hippocampal-hypothalamic-pituitary system," which is loaded with CB-1 receptors. The researchers conclude, however, that the link between marijuana and thermoregulation "does not provide a causal relationship" for what they refer to as "this bizarre learned behavior."

These questions, like many questions having to do with regular marijuana use, are not likely to be answered definitively anytime soon, for a number of good reasons, some of which are delineated by the authors:

--"The legal status of marijuana makes eliciting an accurate drug history challenging."

--"The bizarre hot water bathing is likely often attributed to psychological conditions such as obsessive-compulsive behavior."

--"The knowledge of the anti-emetic effects of cannabis likely disguise cases of cannabinoid hyperemesis, leading to the erroneous belief that cannabis is treating cyclic vomiting rather than causing it."

--"The fact that this syndrome is so recently described and relatively unknown outside an esoteric subset of the GI [gastrointestinal] literature means that most clinicians are unaware of its existence."

Graphics Credit: http://www.oxygentimerelease.com/

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Anandamide Hits the “Hedonic Hot Spot.”

Marijuana and the munchies.

It’s no secret that marijuana very reliably increases appetite. Recently, research published in Nature has teased out an apparent mechanism by which internal cannabinoids are involved with gut microbiota. This affects inflammation, the metabolism of adipose tissue, and other factors implicated in obesity.

In addition, research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and blogged about by Neuroskeptic, showed that CB1 cannabinoid receptors on the tongue selectively boost our pleasurable responses to sweet-tasting food. Conversely, drugs that block cannabinoid receptors have been actively pursued as appetite suppressants. One such drug, trade name rimonabant, was disallowed by the FDA on the grounds that it worked so well in the guise of anandamide’s opposite number that it frequently caused debilitating depression in users. But it did appear to reduce appetites.

Neuroskeptic suggests that a CB1 antagonist that only affects specific sites, like taste buds, might be able to lessen the sweet-tooth effect with fewer complications. “Who knows,” he writes, “in a few years you might even be able to buy CB1 antagonist chewing gum to help you stick to your diet.”

We know that cannabinoids make rats and humans eat more. But how, exactly, does that happen? One reasonable hypothesis is that anandamide, other endocannabinoids, and cannabinoid drugs—anything that tickles the CB1 receptors--must increase sensations of palatability, if eaters are to eat more. A group of University of Michigan researchers chose to investigate the theory that “endogenous cannabinoid neurotransmission in limbic structures such as nucleus accumbens mediates the hedonic impact of natural rewards like sweetness.” They went looking for the precise brain location—the “hedonic hotspot for sensory pleasure”—where endocannabinoids do their work.

Writing in Neuropsychopharmacology in 2007, the investigators sought to discover “if anandamide microinjection into medial nucleus accumbens shell enhances these affective reactions to sweet and bitter tastes in rats.” And it did. Anandamide “doubled the number of  positive ‘liking’ reactions elicited by intraoral sucrose, without altering negative ‘disliking’ reactions to bitter quinine.” Anandamide reliably increased the number of “positive hedonic reactions” the rats showed to sucrose, and never caused any aversive reactions, or increases in water drinking or other behaviors. In addition, the process worked in reverse: “Food-related manipulations, such as deprivation and satiety, or access to a palatable diet produce changes in CB1 receptor density,” leading to higher levels of endogenous anandamide.

positive ‘liking’ reactions elicited by intraoral sucrose, without altering negative ‘disliking’ reactions to bitter quinine.” Anandamide reliably increased the number of “positive hedonic reactions” the rats showed to sucrose, and never caused any aversive reactions, or increases in water drinking or other behaviors. In addition, the process worked in reverse: “Food-related manipulations, such as deprivation and satiety, or access to a palatable diet produce changes in CB1 receptor density,” leading to higher levels of endogenous anandamide.

One location in particular, when dosed with endocannabinoids, increased “liking” responses in the rats threefold. A tiny spot, 1.6 millimeters cubed, but the hottest spot of all: the dorsal half of the medial shell of the nucleus accumbens. At that site, cannabinoid receptors and opioid receptors appear to coexist and interact. If this form of colocalization occurs regularly in rats and humans, it would constitute strong support for the idea that “endocannabinoid and opioid neurochemical signals in the nucleus accumbens might interact to enhance ‘liking’ reactions to the sensory pleasure of sucrose.”

As the authors sum it up, “magnifying the pleasurable impact of food reward” appears to be the baseline effect of endocannabinoids on “appetite or incentive motivation.” Because all of this takes place along the brain’s primary reward pathways in the limbic system, the authors conclude that it would be of interest to know “whether other types of sensory pleasure besides sweetness can be enhanced by the endocannabinoid hedonic hotspot described here.”

Mahler, S., Smith, K., & Berridge, K. (2007). Endocannabinoid Hedonic Hotspot for Sensory Pleasure: Anandamide in Nucleus Accumbens Shell Enhances ‘Liking’ of a Sweet Reward Neuropsychopharmacology, 32 (11), 2267-2278 DOI: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301376

Graphics Credit: NIDA

Labels:

anandamide,

CB1,

endocannabinoids,

marijuana,

munchies

Monday, October 11, 2010

The New Cannabinoids

Army fears influx of synthetic marijuana

It’s a common rumor: Spice, as the new synthetic cannabis-like products are usually called, will get you high--but will allow you to pass a drug urinalysis. And for this reason, rumor has it, Spice is becoming very popular in exactly the places it might be least welcomed: Police stations, fire departments—and army bases.

What the hell is this stuff?

Little is known about spice and other synthetic twists on basic cannabinoid molecules. We do know that the near-cannabis compounds are hard to detect, and even harder to legislate against without closing down avenues of legitimate research. It appears evident that a number of cannabinoid compounds are in circulation, and the precise nature of any given dose is difficult to determine. Much like trying the brown acid, or the joint laced with PCP, the effects vary widely. There are numerous anecdotal reports that spice and its cousins are extremely dose dependent.

The best coverage of Spice, K2, and similar “legal highs” has been generated by science bloggers—especially David Kroll at Terra Sigillata, DrugMonkey at DrugMonkey blog, and Dr. Leigh at Neurodynamics. Readers are advised to consult these links for the most comprehensive coverage of this emerging drug issue.

David Kroll aptly summarized what we know about the "fake weed."

"Synthetic marijuana, marketed as K2 or spice, is an herbal substance sold as an incense or smoking material that remains legal in much of the United States but is being increasingly banned at the state and local levels. The products contain one or more synthetic compounds that behave similarly to the primary psychoactive constituent of marijuana, delta nine tetrahydrocannabinol or THC.”

Kroll writes that JWH–018 is "one of over 100 indoles, pyrroles, and indenes synthesized by the Huffman laboratory to develop cannabimimetics, drugs that mimic the effect of cannabinoids such as THC.”

Furthermore: “The compound most commonly found in these products is a chemical first synthesized by the well-known Clemson University organic chemist, Prof. John W Huffman: the eponymous JW H–018. Another compound, found in spice products sold in Germany, is an analog of CP-47, 497, a cannabinoid developed by Pfizer over 20 years ago."

The cannabimimetics are back.

Unfortunately, the chemical compositions vary, as do the effects, all of which is unpleasantly reminiscent of PCP problems in the past. To gain a better perspective on the matter, I spoke with Joe Gould, a staff writer for the Army Times who has been covering the issue of Spice use in the Armed Forces. Gould has written extensively on the case of Spc. Bryan Roudebush, who attacked his girlfriend in Hawaii while under the influence of Spice. Roudebush had been home from an Iraq deployment for a year when the incident occurred. Two earlier experiences with spice had produced marijuana-like effects. But for Roudebush, the third time was not the charm: He beat his girlfriend and tried to throw her out a window while experiencing what he described as a trance-like state.

“What we were told by the folks at the Army Criminal Investigation Lab is that it started showing up on bases,” said Gould, “and the investigators on the bases were baffled, and the crime lab wasn’t sure what it was at first.”

What investigators discovered was “all that really defines a synthetic cannabinoid is that it activates cannabinoid receptors. We know what THC does. But the chemical composition is not THC. There are all these different strains. Some of the state laws we’ve been seeing, they’re targeting specific varieties of this stuff, but there are other varieties that the law doesn’t know about yet. So I think what the Army has done, intentionally or not, it has sort of skirted this whole question by just calling it all Spice.”

As for the Roudebush case, Gould said: “The first two times he tried it, it was very much like pot. And then the third time, by his and his girlfriend’s description, he goes into a violent trance. They think it was just a different variety. It’s kind of a mystery. What was in that batch? Why did it affect him the way it did? It just goes to how little is known about the drug. You don’t know from one batch to another.”

The U.S. Army currently has no specific testing program in place for Spice. Can you pass a drug test on Spice? “That’s what we heard,” Gould told me. “A researcher from NIH told us exactly that—they believe that the reason it’s popular, the reason they’ve seen officials using it, is because it can’t be tested for.” Despite this, Gould said he knew of “at least nine Commands that have individually passed regulations to target Spice.”

Gould downplayed any talk of an epidemic of usage, and made clear that his research shows that Spice usage is not rampant. “It’s not entirely clear how many soldiers are using Spice. The Army’s not really tracking the use of Spice. Each of these commands passed these regulations either because they saw a problem, or because they were trying to get out in front of what could potentially be a problem.”

Too far out in front for Phillip Cave, a Virginia attorney who has represented military personnel in cases involving Spice. Gould quotes Cave calling the whole thing a “witch hunt,” noting that alcohol is freely available on base, and that researchers do not yet knew whether Spice and its analogs are unsafe or addictive—and they are illegal in only a handful of states at present. Cave also objects to the fact that most cases have been resolved by an Article 15 discharge from service.

“The European Union study says there is the potential for abuse,” said Gould. “How bad it gets, we won’t know until we see more studies.”

Hand-in-hand with restrictions on Spice have come crackdowns on the use of Salvia, a plant responsible for brief but intense bouts of hallucinogenic effects. “The state laws have tended to tackle the two at once,” according to Gould. “Like the state legislatures, the Army has a patchwork of bans they’re putting out there, and there also hitting Salvia. But what I was told by the folks at the lab was that they’re not seeing it in the same kinds of numbers. It’s been sporadic at best.”

Labels:

cannabinoids,

k2,

marijuana,

spice,

Spice Gold,

synthetic marijuana

Sunday, October 3, 2010

Marijuana and Memory

Do certain strains make you more forgetful?

Cannabis snobs have been known to argue endlessly about the quality of the highs produced by their favorite varietals: Northern Lights, Hawaiian Haze, White Widow, etc. Among dedicated potheads, debates about the effects of specific cannabis strains are often overheated, and, ultimately, kind of boring. It's a bit like listening to a discussion of whether the wine in question evinces a woody aftertaste or is, instead, redolent of elderberries. For most people, the true essence of wine drinking is pretty straightforward: a drug buzz, produced by a 12 to 15 % concentration of ethyl alcohol derived from grapes, which can be had in a spectrum of varietal flavors.

However, there is no doubting that, unlike the case of wine, different strains of marijuana can have markedly different psychoactive effects. With weed, it's not just a matter of taste.

Over the past couple of years, the cannabis debate has taken a nasty turn, after British scientists published several controversial studies suggesting that high-THC "skunk" cannabis was responsible for increased mental problems among young people--including an increased risk of developing the symptoms of schizophrenia. British drug policy makers have continued to lead the charge on this, with mixed results. See my earlier post.

Recently, a study published in the British Journal Of Psychiatry concluded that marijuana

high in THC--including so-called "skunk" cannabis--caused markedly more memory impairment than varieties of marijuana containing less THC.

high in THC--including so-called "skunk" cannabis--caused markedly more memory impairment than varieties of marijuana containing less THC.

In an article at Nature News, Arran Frood spelled out the details of the study:

"Curran and her colleagues traveled to the homes of 134 volunteers, where the subjects got high on their own supply before completing a battery of psychological tests designed to measure anxiety, memory recall and other factors such as verbal fluency when both sober and stoned. The researchers then took a portion of the stash back to the laboratory to test how much THC and cannabidiol it contained.... Analysis showed that participants who had smoked cannabis low in cannabidiol were significantly worse at recalling text than they were when not intoxicated. Those who smoked cannabis high in cannabidiol showed no such impairment."

The two main ingredients in cannabis are THC and cannabidiol (CBD). CBD shows less affinity for the two main types of cannabis receptors, CB1 and CB2, meaning that it attaches to receptors more weakly, and activates them less robustly, than THC. The euphoric effects of marijuana are generally attributed to THC content, not CBD content. In fact, there appears to be an inverse ratio at work. According to a paper in Neuropsychopharmacology, "Delta-9-THC and CBD can have opposite effects on regional brain function, which may underlie their different symptomatic and behavioral effects, and CBD's ability to block the psychotogenic effects of delta-9-THC."

So, CBD specifically does not produce the usual marijuana high with accompanying euphoria and forgetfulness and munchies. What the researchers found was that pot smokers suffering memory impairment and those showing normal memory "did not differ in the THC content of the cannabis they smoked. Unlike the marked impairment in prose recall of individuals who smoked cannabis low in cannabidiol, participants smoking cannabis high in cannabidiol showed no memory impairment."

As far as memory goes, THC content didn't seem to matter. It was the percentage of CBD that controlled the degree of memory impairment, the authors concluded. "The antagonistic effects of cannabidiol at the CB1 receptor are probably responsible for its profile in smoked cannabis, attenuating the memory-impairing effects of THC. In terms of harm reduction, users should be made aware of the higher risk of memory impairment associated with smoking low-cannabidiol strains of cannabis like 'skunk' and encouraged to use strains containing higher levels of cannabidiol."

The idea that cannabidiol may protect against THC-induced memory loss is still quite speculative. Other research has suggested that a paucity of CB1 receptors may be protective against memory impairment. Marijuana growers select for high-THC strains, not high-CBD strains, and thus there is little data available about the CBD levels of most marijuana.

An earlier study in Behavioural Pharmacology by Aaron Ilan and others at the San Francisco Brain Research Institute did not find any connection between memory and CBD content. However, Ilan speculated in the Nature News article that the difference might have been due to methodology: In Britain, the subjects were studied using marijuana of their own choosing. In the U.S., National Institute of Health research policy has decreed that marijuana for official research must be supplied by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). And if there is one thing many researchers seem to agree on, it is that NIDA weed "is notorious for being low in THC and poor quality."

But CBD still does something, and that something just might be pain relief. Lester Grinspoon, a long-time marijuana researcher at Harvard Medical School, thinks that if the study proves out, it could have an important impact on the medical use of marijuana. Also quoted in Nature News, Grinspoon said: "Cannabis with high cannabidiol levels will make a more appealing option for anti-pain, anti-anxiety and anti-spasm treatments, because they can be delivered without causing disconcerting euphoria."

Morgan, C., Schafer, G., Freeman, T., & Curran, H. (2010). Impact of cannabidiol on the acute memory and psychotomimetic effects of smoked cannabis: naturalistic study The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197 (4), 285-290 DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077503

Graphics Credit: http://sites.google.com

Labels:

cannabis,

CB1,

CBD,

marijuana,

marijuana and memory,

memory impairment,

THC

Thursday, November 19, 2009

The Dutch Smoke Less Pot

One of those inconvenient truths.

Government drug policy experts don’t like the numbers, which is one of the reasons why you probably haven’t seen them. Among the nations of Europe, the Netherlands is famous, or infamous, for its lenient policy toward cannabis use—so it may come as a surprise to discover that Dutch adults smoke considerably less cannabis, on average, than citizens of almost any other European country.

A recent report by Reed Stevenson for Reuters highlights figures from the annual report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, which shows the Dutch to be at the low end for marijuana usage, compared to their European counterparts. The report pegs adult marijuana usage in the Netherlands at 5.4 %. Also at the low end of the scale, along with the Netherlands, were Romania, Greece, and Bulgaria.

Leading the pack was Italy, at 14.6 %, followed closely by Spain, the Czech Republic, and France.

While cannabis use rose steady in Europe throughout the 1990s, the survey this year says that the data “point to a stabilising or even decreasing situation.” The study by the European Monitoring Centre did not include figures for countries outside Europe.

According to the Dutch government, Amsterdam is scheduled to close almost 20 per cent of its existing coffee shops—roughly 50 outlets--because of their proximity to schools. However, some local coffee shop proprietors maintain that far fewer shops, perhaps no more than 10 or 20, will actually be required to close.

What are the Dutch doing right? Are coffee shops the answer? It may be prove to be the case that cannabis coffee shops can’t be made to work everywhere—that the Dutch approach is, well, Dutch. However, the fact that it works reasonably well, if not perfectly, in the Netherlands is strong testimony on behalf of the idea of harm reduction.

Here are some excerpts from a flyer given out at some Dutch coffee shops by a group of owners known as the BCD, or Union of Cannabis Shop Owners:

--Do not smoke cannabis every day.

--There are different kinds of cannabis with different strengths, so be well informed.

--The action of alcohol and cannabis can amplify each other, so be careful when smoking and drinking at the same time.

--Do not use cannabis during pregnancy!

--Consult your doctor before using cannabis in combination with any medications you may be taking.

--Note that smoking is bad for your health anyway.

--Do not buy your drugs on the street, just look for a coffeeshop.

Customers must be over the age of 18, and in most coffee shops, as in bars and restaurants in the Netherlands and elsewhere, cigarette smoking is no longer allowed.

Photo Credit: www.us.holland.com

Labels:

dutch coffee shops,

harm reduction,

marijuana,

marijuana laws

Thursday, May 28, 2009

Marijuana Legalization Is Coming, Says Pollster

Nate Silver reads the numbers.

Last month, I missed this crucial article, penned by the inestimable Nate Silver. Silver, you may recall, is the numbers nerd who shamed all conventional pollsters during the run-up to the presidential election—and then proceeded to predict the Electoral College vote with perfect accuracy.

So when Nate Silver takes a hard look at statistics having to do with American sentiment about marijuana legalization, it behooves us to take his findings seriously. In an April 5 post called “Why Marijuana Legalization is Gaining Momentum,” on his FiveThirtyEight.com blog, Silver lays out the inevitable chronology.

“Back in February, we detailed how record numbers of Americans -- although certainly not yet a majority -- support the idea of legalizing marijuana,” Silver writes. “It turns out that there may be a simple explanation for this: an ever-increasing fraction of Americans have used pot at some point in their lifetimes.”

According to Silver’s number crunching, the peak pot year in anyone’s life is on or about age 20—duh—with most people reaching some sort of usage plateau between the ages of 30 and 50. The important point, Silver writes, has to do with the fraction of adults who have used. This is a dual-peaked distribution, “with one peak occurring among adults who are roughly age 50 now, and would have come of age in the 1970s, and another among adults in their early 20s. Generation X, meanwhile, in spite of its reputation for slackertude, were somewhat less eager consumers of pot than the generations either immediately preceding or proceeding them.”

Furthermore, reports of lifetime usage drop off precipitously after 55. “About half of 55-year-olds have used marijuana at some point in their lives, but only about 20 percent of 65-year-olds have.”

What does this tell us? While there is certainly not an exact correspondence between people who have smoked pot and people who support legalization, Silver ventures to guess that the link is fairly strong. What we have here, he argues, is a “fairly strong generation gap when it comes to pot legalization. As members of the Silent Generation are replaced in the electorate by younger voters, who are more likely to have either smoked marijuana themselves or been around those that have, support for legalization is likely to continue to gain momentum.”

Photo: Minnesotaindependent.com

Sunday, December 16, 2007

Harm Reduction: The Dutch Experience

Does marijuana decriminalization work?

Decriminalization of certain drug offenses is one of the goals of a loosely organized movement called harm reduction. While it neither ignores the dangers of addictive drugs, nor advocates their use, harm reduction, as practiced by organizations like the Harm Reduction Coalition, is a limited step that calls for making distinctions between major and minor classes of drug crimes. Above all, it is a practical approach.

According to the International Harm Reduction Association: “In many countries with zero tolerance drug policies, funding for drug law enforcement is five to six times greater than funding for prevention and treatment.” In place of that scenario, harm reduction strategies aim for the creation of non-coercive, community-based recovery programs and resources for drug users. The association defines harm reduction as follows: “Policies and programs which attempt primarily to reduce the adverse health, social, and economic consequences of mood altering substances to individual drug users, their families and their communities.”

Harm reduction strategies do not call upon the government to eradicate the drug problem. Nor would they ultimately lead to cocaine and heroin being sold in government-owned versions of mom-and-pop drugstores. It calls for judgment and discrimination on the part of law enforcement agencies, judges, juries, lawyers, and everyday citizens. The controversial Dutch experiment with harm reduction is often the focal point of such discussions. In 1976, the Dutch made a misdemeanor out of the sale of up to one ounce of cannabis. In the Netherlands, possession of marijuana and heroin is illegal, but there are certain well-defined exceptions, such as the Amsterdam coffee houses, where marijuana and hashish may be freely purchased and consumed. The coffee houses pay taxes on their marijuana sales, just as they do with sales of beer.

The price of marijuana and hashish available in the shops is reasonably low, which cuts back on the need to commit crimes in order to pay for it, and lowers the profits available to street dealers. “If we kept chasing grass or hashish, the dealers would go underground, and that would be dangerous,” a senior Dutch police officer told The Economist (sub. required).

The Dutch officer insisted that the Dutch do not intend to reverse course, as happened in Alaska. “The Americans offer us big money to fight the war on drugs their way. We do not say that our way is right for them, but we are sure it is right for us. We don’t want their help.”

Dutch police still possess strong enforcement powers when it comes to hard drugs, but they have been instructed to view the issue as a public health problem. Heroin addicts are tolerated, but steered in the direction of treatment. By some accounts, 75 per cent of Dutch heroin addicts are involved in one treatment program or another. Local officials complain that some of their drug problem can be traced to a flood of young people coming in from other countries where stricter drug laws are in force.

The Dutch experiment rests on the belief that drug addiction is a medical problem, and that medical problems cannot be solved within the structure of the criminal justice system. “The lifetime prevalence of cannabis use in the Netherlands for 10- to 18-year-olds is 4.2 per cent,” Science (sub. required) reported, “compared with the U.S. High School Survey figure of approximately 30 per cent.”

Wednesday, August 1, 2007

Media Suffers Attack of Cannabis Psychosis

Bad Science Makes for Bad Science Journalism

According to the London Daily Mail, smoking a single joint of marijuana increases your risk of developing schizophrenia by 41 per cent. The Mail quoted Professor Robin Murray of the Institute of Psychiatry in London, who dutifully warned that the risk was perhaps even higher than that, due to the increasing use of what the newspaper termed “powerful skunk cannabis.” The skunk effect, said Murray, meant that the study’s estimate that “14 per cent of cases of schizophrenia in the UK are due to cannabis is now probably an understatement.”

Marjorie Wallace of the mental health charity SANE told BBC News: “The headlines are not scaremongering, but reflect a daily, and preventable, tragedy.”

Wow. As Gertrude Stein once put it, “Interesting if true.”

But it’s not true at all, of course. Or, to put it more accurately: If it were true, there is no way in hell the meta study under question could be used to prove it.

Speaking as a science journalist, this is the sort of thing than can really ruin your day.

As always, it helps to start with the original published article, a meta-analysis published in the British medical journal Lancet under the title, “Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review.” 2007 370: 319-28. Mark Hoofnagle, a MD/PhD Candidate in the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics at the University of Virginia, discussed the paper in depth on his Denialism Blog:

“First of all, the statement that ‘just one joint’ increases risk by 41% is absurd. The study here is of those who have tried marijuana once or more, not of people who have only tried it once. So already, the Daily Mail and every other news organization is way off. Second, I think we're ultimately seeing a post-hoc ergo propter hoc argument, and a dose-response that's more characteristic of the population studied than a real pharmacologic effect.”

Here’s why:

--People who suffer from a mental illness do more drugs than “normal” people. They are a high-risk population when it comes to addiction. There are people who have a propensity for addiction, and people who do not. Many of those who do will get hooked, but this does not mean that everything which follows is a result of the drugs.

--Latent schizophrenics often suffer their first break while under the influence of psychoactive drugs. Pot, along with LSD, physical trauma, the death of a loved one, and other intense emotional events can all trigger a schizophrenic break in late adolescence. So naturally there would be a correlation.

--The assumption that pot causes susceptibility to mental illness, rather than the other way around, can’t be proven. Hoofnagle uses the example of cigarette smoking. Anyone who has researched schizophrenia, or been around schizophrenics, knows that almost all schizophrenics smoke. (It helps quell hallucinations). Most of them began to smoke before the onset of their illness. Using the assumptions of the current study, we could say that cigarette smoking is almost certain to cause schizophrenia. Correlation, as Hoofnagle reminds us, is not causation.

--Daily pot smokers confound such a study. Are some of them exhibiting symptoms of schizophrenia, or are they exhibiting the symptoms of chronic marijuana intoxication? If they quit smoking so much, would they stop acting so crazy?

--Comorbidity is exceedingly common in drug addicts and users. There is a well-documented causal connection between depression and the use of psychoactive drugs. People suffering from depression often resort to cannabis and other drugs as a form of self-medication. Again, the mental condition leads to the drug use, and not the other way around.

--Finally, where is the epidemic of schizophrenia caused by millions of people smoking marijuana for years? What field evidence can be drawn upon to support this remarkable conclusion?

To be fair to the authors, bets are hedged. In their conclusion, Moore, et.al. state: “The possibility that this association results from confounding factors or bias cannot be ruled out, and these uncertainties are unlikely to be resolved in the near future.”

Nevertheless, the authors go on to conclude that “We believe that there is now enough evidence to inform people that using cannabis could increase their risk of developing a psychotic illness later in life.”

At www.badscience.net, Ben Goldacre wryly notes that “You know when cannabis hits the news you’re in for a bit of fun…” Of 175 studies identified as potentially relevant, Goldacre maintains that only 11 papers, describing 7 discrete data sets, actually turned to be relevant for purposes of the study. If every assumption in the paper is taken to be correct, and causality is accepted, Goldacre calculated, about 800 cases of schizophrenia per year could be attributed to marijuana in the U.K. “But what’s really important,” Goldacre writes, “is what you do with this data. Firstly you can misrepresent it….not least of all with the ridiculous ‘modern cannabis is 25 times stronger’ fabrication so beloved by the media and politicians.”

As it happens, all of this comes at a time in Britain when efforts to reclassify cannabis are being hotly debated in the government. As propaganda, the report is useful, but as a means of clarifying the debate, it will only produce confusion and demagoguery.

Sources:

--Moore, Theresa H.M., et. Al. “Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review.” Lancet. 2007 370: 319-28 http://www.thelancet.com/

--MacCrae, Fiona and Andrews, Emily. “Smoking just one cannabis joint raises danger of mental illness by 40%.” London Daily Mail. 26/07/07

--“Cannabis ‘raises psychosis risk.’” BBC News. 2007/07/27 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6917003.stm

--Cressey, Daniel. “Medical opinion comes full circle on cannabis dangers.” Nature. 27 July 2007.

--Hoofnagle, Mark. “Does Smoking Cannabis Cause Schizophrenia?” Denialism Blog. July 30, 2007. http://scienceblogs.com/denialism/2007/07/does_smoking_cannabis_cause_sc.php

Labels:

addiction,

cannabis,

marijuana,

psychosis,

schizophrenia,

withdrawal

Friday, July 27, 2007

Minister Says Marijuana is a Sacrament

That’s Reverend Stoner to you, brother

Nice try, Craig X. Rubin. But the California courts aren’t buying it. Ministers, mail-order or otherwise, are unlikely to merit federal protection for the use of pot as a church sacrament.

Ordained, as were so many of us, as a minister of the Universal Life Church, and thereby licensed to perform legal weddings and, in days gone by, to attempt conscientious objector status in military matters, Rubin was charged with possession with attempt to sell. The leader of the 420 Temple faces up to seven years in prison for dealing.

The 41 year-old Rubin has no legal experience but is representing himself in the case. Not much is known about his court strategy, but a two-pronged defense appeared to be emerging: Rubin will argue that marijuana is the “tree of life” mentioned in the Bible (if not in the movie, “The Fountain,”) and that an officer held a shotgun to his head during the arrest. He is not contesting the allegation of possessing pot, which he said the churches uses as a sacrament during services. He is currently free on $20,000 bail.

Rubin spent last weekend preparing for jury selection by consulting with Native American elders in as sweat lodge at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. This may not be as crazy as it sounds, as tribes in the West have accumulated considerable legal expertise in these matters due to the use of peyote in Native American Church rituals.

“He is as good as I’ve seen any defendant representing himself,” said Michael Levinsohn of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML).

In the event, Superior Court Judge Mary H. Strobel neatly side-stepped the federal issues at hand, ruling that the Reverent Rubin could not use federal statutes as a defense against state drug charges.

Sources:

--Glazer, Andrew. “Minister cites religious protection in marijuana defense.” Associated Press Newswire, 07/24/2007

--“Minister: Marijuana is a sacrament.” Focus on Faith, MSNBC.com. July 26, 2007. http://www.msnbc.msn.com

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

New World Nicotine: A Brief History

“Drinking the Smoke”

The prototypically North American contribution to the world drug trade has always been tobacco. Tobacco pipes have been found among the earliest known Aztec and Mayan ruins. Early North Americans apparently picked up the habit from their South American counterparts. Native American pipes subjected to gas chromatography show nicotine residue going back as far as 1715 B.C. “Drinking” the smoke of tobacco leaves was an established New World practice long before European contact. An early technique was to place tobacco on hot coals and inhale the smoke with a hollow bone inserted in the nose.

The addicting nature of tobacco alarmed the early missionary priests from Europe, who quickly became addicted themselves. Indeed, so enslaved to tobacco were the early priests that laws were passed to prevent smoking and the taking of snuff during Mass.

New World tobacco quickly came to the attention of Dutch and Spanish merchants, who passed the drug along to European royalty in the 17th Century. In England, American tobacco was worth its weight in silver, and American colonists fiercely resisted British efforts to interfere with its cultivation and use. Sir Francis Bacon noted that “The use of tobacco is growing greatly and conquers men with a certain secret pleasure, so that those who have once become accustomed thereto can later hardly be restrained therefrom.” (As a former smoker, I am hard pressed to imagine a better way of putting it.)

Early sea routes and trading posts were determined in part by a desired proximity to overseas tobacco plantations. The expedition routes of the great 17th and 18th Century European explorers were marked by the strewing of tobacco seeds along the way. Historians estimate that the Dutch port of Amsterdam had processed more than 12 million pounds of tobacco by the end of the 17th Century, with brisk exports to Scandinavia, Russia, Prussia, and Turkey. (Historian Simon Schama has speculated that a few enterprising merchants in the Dutch tobacco industry might have “sauced” their product with cannabis sativa from India and the Orient.)

Troubled by the rising tide of nicotine dependence among the common folk, Bavaria, Saxony, Zurich, and other European states outlawed tobacco at various times during the 17th Century. The Sultan Murad IV decreed the death penalty for smoking tobacco in Constantinople, and the first of the Romanoff czars decreed that the punishment for smoking was the slitting of the offender’s nostrils. Still, there is no evidence to suggest that any culture that has ever taken up the smoking of tobacco has ever wholly relinquished the practice voluntarily.

A century later, the demand for American tobacco was growing steadily, and the market was worldwide. Prices soared, with no discernible effect on demand. “This demand for tobacco formed the economic basis for the establishment of the first colonies in Virginia and Maryland,” according to drug researcher Ronald Siegel. Furthermore, writes Siegel, in his book “Intoxication”:

"The colonists continued to resist controls on tobacco. The tobacco industry became as American as Yankee Doodle and the Spirit of Independence…. British armies, trampling across the South, went out of their way to destroy large inventories of cured tobacco leaf, including those stored on Thomas Jefferson’s plantation. But tobacco survived to pay for the war and sustain morale."

In many ways, tobacco was the perfect American drug, distinctly suited to the robust American lifestyle of the 18th and 19th Centuries. Tobacco did not lead to debilitating visions or rapturous hallucinations—no nodding out, no sitting around wrestling with the angels. Unlike alcohol, it did not render them stuporous or generally unfit for labor. Tobacco acted, most of the time, as a mild stimulant. People could work and smoke at the same time. It picked people up; it lent itself well to the hard work of the day and the relaxation of the evening. It did not act like a psychoactive drug at all.

As with plant drugs in other times and cultures, women generally weren’t allowed to use it. Smoking tobacco was a man’s habit, a robust form of relaxation deemed inappropriate for the weaker sex. (Women in history did take snuff, and cocaine, and laudanum, and alcohol, but mostly they learned to be discreet about it, or to pass it off as doctor-prescribed medication for a host of vague ailments, which, in most cases, it was.)

Excerpted from The Chemical Carousel: What Science Tells Us About Beating Addiction © Dirk Hanson 2008, 2009.

By Dirk Hanson

Labels:

addiction,

addictive,

cigarettes,

drug addiction,

drugs,

marijuana,

nicotine

Sunday, June 24, 2007

Does AA Work?

Bill W., co-founder of AA

Adapted from The Chemical Carousel: What Science Tells Us About Beating Addiction © Dirk Hanson 2008, 2009.

Despite recent progress in the medical understanding of addictive disease, the amateur self-help group known as Alcoholics Anonymous, and its affiliate, Narcotics Anonymous, are still regarded by many as the most effective mode of treatment for the ex-addict who is serious about keeping his or her disease in remission. A.A. and N.A. now accept anyone who is chemically dependent on any addictive drug—those battles are history. In today’s A.A. and N.A., an addict is an addict. A pragmatic recognition of pan-addiction makes a hash of strict categories, anyway.

Nonetheless, under the biochemical paradigm of addiction, we have to ask whether the common A.A.-style of group rehabilitation, and its broader expression in the institutionalized form of the Minnesota Model, are nothing more than brainwashing combined with a covert pitch for some of that old-time religion. As Dr. Arnold Ludwig has phrased it, “Why should alcoholism, unlike any other ‘disease,’ be regarded as relatively immune to medical or psychiatric intervention and require, as AA principles insist, a personal relationship with a Higher Power as an essential element for recovery?”

The notion is reminiscent of earlier moralistic approaches to the problem, often couched in strictly religious terms. It conjures up the approach sometimes taken by fundamentalist Christians, in which a conversion experience in the name of Jesus is considered the only possible route to rehabilitation. But if all this is so, why do so many of the hardest of hard scientists in the field continue to recommend A.A. meetings as part of treatment? Desperation? Even researchers and therapists who don’t particularly like anything about the A.A. program often reluctantly recommend it, in the absence of any cheap alternatives.

In 1939, Bill Wilson and the fellowship of non-drinkers that had coalesced around him published the basic textbook of the movement, Alcoholics Anonymous. The book retailed for $3.50, a bit steep for the times, so Bill W. compensated by having it printed on the thickest paper available—hence its nickname, the “Big Book.” The foreword to the first printing stated: “We are not an organization in the conventional sense of the word. There are no fees or dues whatsoever. The only requirement for membership is an honest desire to stop drinking. We are not allied with any particular faith, sect or denomination, nor do we oppose anyone. We simply wish to be helpful to those who are afflicted.”

In short, it sounded like a recipe for complete disaster: naive, hopeful, objective, beyond politics, burdened with an anarchical structure, no official record

keeping, and a membership composed of anonymous, first-name-only alcoholics.

......................

Amid dozens of case histories of alcoholics, the Big Book contained the original Twelve Steps toward physical and spiritual recovery. There are also Twelve Traditions, the fourth one being, “Each group should be autonomous except in matters affecting other groups or A.A. as a whole.” As elaborated upon in Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, “There would be real danger should we commence to call some groups ‘wet’ or ‘dry,’ still others ‘Republican’ or ‘Communist’…. Sobriety had to be its sole objective. In all other respects there was perfect freedom of will and action. Every group had the right to be wrong. The unofficial Rule #62 was: “Don’t take yourself too damn seriously!”

As a well-known celebrity in A.A. put it: “In Bill W.’s last talk, he was asked what the most important aspect of the program was, and he said it was the principle of anonymity. It’s the spiritual foundation.” Co-founder Dr. Bob, for his part, believed the essence of the Twelve Steps could be distilled into two words—“love” and “service.” This clearly links the central thrust of A.A. to religious and mystical practices, although it is easily viewed in strictly secular terms, too.

Alcoholics Anonymous recounts a conversation “our friend” had with Dr. C.G. Jung. Once in a while, Jung wrote, “…alcoholics have had what are called vital spiritual experiences…. They appear to be in the nature of huge emotional displacements and rearrangements.” As stated in Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, “Nearly every serious emotional problem can be seen as a case of misdirected instinct. When that happens, our great natural assets, the instincts, have turned into physical and mental liabilities.”

Alcoholics Anonymous asserts that there are times when the addict “has no effective mental defense” against that first drink.

Bill Wilson wrote:

"Some strongly object to the A.A. position that alcoholism is an illness. This concept, they feel, removes moral responsibility from alcoholics. As any A.A. knows, this is far from true. We do not use the concept of sickness to absolve our members from responsibility. On the contrary, we use the fact of fatal illness to clamp the heaviest kind of moral obligation onto the sufferer, the obligation to use A.A.’s Twelve Steps to get well."

This excruciating state of moral and physical sickness—this “incomprehensible demoralization”—is known in A.A. as hitting bottom. “Why is it,” asks Dr. Arnold Ludwig, “that reasonably intelligent men and women remain relatively immune to reason and good advice and only choose to quit drinking when they absolutely must, after so much damage has been wrought? What is there about alcoholism, unlike any other ‘disease’ in medicine except certain drug addictions, that makes being in extremis represent a potentially favorable sign for cure?”

Hitting bottom may come in the form of a wrecked car, a wrecked marriage, a jail term, or simple the inexorable buildup of the solo burden of drug-seeking behavior. While the intrinsically spiritual component of the A.A. program would seem to be inconsistent with the emerging biochemical models of addiction, recall that A.A.’s basic premise has always been that alcoholism and drug addiction are diseases of the body and obsessions of the mind.

When the shocking moment arrives, and the addict hits bottom, he or she enters a “sweetly reasonable” and “softened up” state of mind, as A.A. founder Bill Wilson expressed it. Arnold Ludwig calls this the state of “therapeutic surrender.” It is crucial to everything that follows. It is the stage in their lives when addicts are prepared to consider, if only as a highly disturbing hypothesis, that they have become powerless over their use of addictive drugs. In that sense, their lives have become unmanageable. They have lost control.

A.A.’s contention that there is a power greater than the self can be seen in cybernetic terms—that is to stay, in strictly secular terms. The higher power referred to in A.A. may simply turn out to be the complex dynamics of directed group interaction, i.e., the group as a whole. It is a recognition of holistic processes beyond a single individual—the power of the many over and against the power of one.

“The unit of survival—either in ethics or in evolution—is not the organism or the species,” wrote anthropologist Gregory Bateson, “but the largest system or ‘power’ within which the creature lives.” In behavioral terms, A.A. enshrines this sophisticated understanding as a first principle.

Labels:

AA,

addiction,

alcohol,

alcoholics anonymous,

alcoholism,

Bill W.,

counseling,

marijuana,

psychology,

rehab

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)