Monday, May 6, 2013

Clock Ticking On Colorado’s Marijuana Repeal Bill

Proposal to revote on pot legalization is losing steam.

While the rest of the nation argues over Colorado’s recent decision to legalize limited amounts of marijuana, a small but determined group of legislators in that state have been promoting a bill that would allow a “conditional repeal” of the pot amendment.

The proposal to resubmit the question of retail marijuana sales to Colorado voters is supported by Senate President John Morse (D-Colorado Springs) and Senate Minority Leader Bill Cadman (R-Colorado Springs).* The proposed ballot measure would first ask voters to approve previously promised higher tax rates on marijuana. On April 29, the Colorado House passed a bill placing a 15% excise tax and a 10% sales tax on marijuana, and came up with the idea of submitting the plan to the voters as a ballot proposal. If the higher tax doesn’t pass, citizens would then be asked whether retail sales should be repealed. “People voted for marijuana and tax,” said State Senator Morse, “and what they got was marijuana and we’ll see if they get the tax."

Republican Senator Larry Crowder (R-Alamosa) and others point to the fact that Amendment 64 called for $40 million in new excise taxes for state school funds, in addition to the legal cultivation of 6 plants and possession of a ounce or less. “So if there’s no money,” Crowder told a Denver TV station, “we shouldn’t have marijuana.”

“The marijuana legalization repeal — or suspension — proposal would also have to be approved by voters,” according to the Denver Post. “But, before it could reach the ballot, it would need two-thirds support in the Capitol because it would change a provision of Colorado's constitution.”

Today is the last day that House Bill 1380 can move forward in the final hours of Colorado’s legislative session, a disheartening prospect for marijuana supporters, faced with the notion of fighting the fight all over again. The Boulder Weekly called it “a sneak attack on Amendment 64.” But it appears that most of the steam has leaked out of the repeal drive. Rep. Dan Pabon (D-Denver) told the Post that “there was a pretty strong grassroots response that I think every member received that said, 'Don't threaten us.'"

Here’s how SMART Colorado, a group opposing legalization, puts the argument: “Amendment 64 raised the possibility of new taxes on marijuana but didn’t enact them. If voters don’t now approve new taxes on marijuana, Colorado’s budget will take a major hit and Amendment 64 will have exactly the opposite effect from what was promised voters.”

Supporters of state legalization claim the legislators are trying to change the rules in midstream, by asking voters to approve a sales tax that is higher than necessary. Mason Tvert of the Marijuana Policy Project claims the move amounts to “extortion of the voters. They’re being told they must approve a higher tax level proposed by legislators or otherwise the constitutional amendment they adopted in November will be repealed.”

The measure’s chances are slim in the Colorado legislature—a group altogether mindful of the 55% margin by which voters passed the original amendment.

Meanwhile, in the state of Washington, legalization plans ran up against a major hurdle when it was discovered that the current law defines marijuana, the drug, as anything with more than 0.3 % THC content. Unfortunately for the state’s crime lab, that bar is so low that law enforcement actions against large grower operations and possession of large quantities would founder over the fact that most of what cops seized would be defined, in effect, as hemp. Yes, the state of Washington managed to criminalize the large-scale possession of hemp, so the House and Senate quietly scrambled to re-criminalize large-scale marijuana possession, not hemp possession, by defining THC content more scientifically.

This is only a snapshot of the regulatory issues that await attention in Washington and Colorado, as they attempt to become the first states to navigate new waters and divorce themselves from federal drug policy imperatives. There is still a very long way to go. In a speech in Mexico City last Friday, President Obama firmly closed the door on the idea that the feds might be persuaded to support state marijuana legalization efforts.

*Late Monday night, the bill's sponsors backed off, and the marijuana repeal proposal died for lack of support.

Graphics Credit: http://blog.sfgate.com http:/

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Where Are All the New Anti-Craving Drugs?

The dilemma of dwindling drug development.

Drugs for the treatment of addiction are now a fact of life. For alcoholism alone, the medications legally available by prescription include disulfiram (Antabuse), naltrexone (Revia and Vivitrol)—and acamprosate (Campral), the most recent FDA-approved entry. A fourth entry, topiramate (Topamax), is currently only approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for other uses. But none of these are miracle medications, and more to the point, no bright new stars have come through the FDA pipeline for a long time.

New approvals for drugs in this category, like psychiatric drugs in general, have lately been confined to repurposed, “me-too” medications—which, insurance companies complain, are far too expensive. As health insurance giant Cigna explains on its website: “If anticraving medications are not covered by your insurance plan, keep in mind that the price of anticraving medications is usually small compared to the cost of alcohol and/or other drugs.” Perhaps so, but evidently not small enough for the expense to be routinely covered by the prescription portion of insurance policies.

Federal health officials have the same complaints. In a 2004 report entitled “Innovation or Stagnation: Challenge and Opportunity on the Critical Path to New Medical Products,” the U.S. Food and Drug Administration called for increased public-private collaboration and a “critical development path that leads from scientific discovery to the patient.”

As detailed by Professor Mary Jeanne Kreek, a senior attending physician at the Laboratory of the Biology of Addictive Diseases at Rockefeller University and one of the primary developers of methadone therapy:

Toxicity, destruction of previously formed synapses, formation of new synapses, enhancement or reduction of cognition and the development of specific memories of the drug of abuse, which are coupled with the conditioned cues for enhancing relapse to drug use, all have a role in addiction. And each of these provides numerous potential targets for pharmacotherapies for the future.

In other words, when an addiction has been active for a sustained period, the first-line treatment of the future is likely to come in the form of a pill. New addiction treatments will come—and in many cases already do come—in the form of drugs to treat drug addiction. Every day, addicts are quitting drugs and alcohol by availing themselves of pharmaceutical treatments that did not exist twenty years ago.

But things have changed. “This scientific stall may have seemed to come out of the blue,” writes Dr. Steven E. Hyman, Professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard University, in the Dana Foundation publication, Cerebrum. Hyman sketches a dismal picture:

The molecular and cellular underpinnings of psychiatric disorders remain unknown; there is broad disillusionment with the animal models used for decades to predict therapeutic efficacy; psychiatric diagnoses seem arbitrary and lack objective tests; and there are no validated biomarkers with which to judge the success of clinical trials. As a result, pharmaceutical companies do not see a feasible path to the discovery and development of novel and effective treatments…. progress for the many patients who respond only partially or not at all to current treatments requires the discovery of medications that act differently in the brain than the limited drugs that we now possess…. and regulatory agencies have given up their willingness to accept even more expensive new drugs.

Genes aren’t simple, and the kinds of studies that would lead to new anti-craving drugs are not cheap. Moreover, the medications themselves do not represent cures. Even if drugs that block dopamine receptors treat psychotic symptoms, Hyman writes, “it does not follow that the fundamental problem is excess dopamine any more than pain relief in response to morphine suggests that the original problem is a deficiency of endogenous opiates.”

What can change this picture for the better? “One exciting recent development is the emerging recognition that genes involved in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism do not represent a random sample of the genome,” Hyman writes. “Rather, the genes are beginning to coalesce into identifiable biochemical pathways and components of familiar neural structures…. Many researchers hope that such efforts will help attract the pharmaceutical industry back to psychiatry by demonstrating new paths to treatment development. The emerging genetic results may be the best clues we have ever had to the etiology of psychiatric disorders.”

Detractors worry, naturally enough, about the shrinking pie of funds available for this sort of endeavor. According to Steven Paul, president of Lilly Research Laboratories, “I am worried that obtaining the kind of molecular probes required for even in vivo testing may prove to be too time-consuming and expensive, and may divert precious NIH funds away from basic or clinical biomedical research.”

But Hyman remains optimistic, “based partly on the extraordinary vitality of neuroscience and perhaps, even more important, on the emergence of remarkable new tools and technologies to identify the genetic risk factors for psychiatric disorders, to investigate the circuitry of the human brain, and to replace current animal models that have failed to predict efficacious new drugs that act by novel mechanisms in the brain.”

Photo Credit: http://www.insidecounsel.com/

Sunday, April 28, 2013

Addiction Inbox (D)Evolves Into Paperback

A curated collection of blog posts in print.

Online is where journalism is happening now, but it is a truism that most of the world’s repository of knowledge is still found in books. It is also true that Addiction Inbox now comes in paperback, from Amazon. For cheap. Also available in Kindle, for unbelievably cheap.

I have selected and arranged a “best of the blog” collection, meant to serve as a handy off-the-shelf compendium of science-based information on drugs and addiction. Is shoplifting the opiate of the masses? Does menthol really matter? Can ketamine and other party drugs cause permanent bladder damage? The posts are arranged in four sections: Research, The New Synthetics, Treatment, and Interviews/Book Reviews. This 330-page anthology of articles is designed to bring multiple perspectives to bear on questions of drugs, addiction, and treatment. For just ridiculously cheap.

Cassie Rodenberg at Scientific American’s White Noise blog was kind enough to review Addiction Inbox, the book: “The author relates the real life to the scientific, noting his own struggles with addiction, yet doesn’t get bogged down in personal tales. Rather, the writings use life tidbits as jumping off points for scientific explanation and an overarching discussion of addiction’s media landscape.”

Which was pretty much what I was hoping to do when I started this blog….

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Nature, Nurture, and Me

Which came first, the addiction or the trauma?

About a year ago, Jonathan Taylor, a professor at California State University in Fullerton, assigned his students some reading from my book, The Chemical Carousel, for his “Drugs, Politics, and Cultural Change” course. At the same time, the class watched an interview with Dr. Gabor Maté, author of In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction. In a letter written for his readers, Dr. Mate´ insists that addiction “is very close to the core of the human experience. That is why almost anything can become addictive, from seemingly healthy activities such as eating or exercising to abusing drugs intended for healing. The issue is not the external target but our internal relationship to it. Addictions, for the most part, develop in a compulsive attempt to ease one’s pain or distress in the world…. The more we suffer, and the earlier in life we suffer, the more we are prone to become addicted."

I find this perspective interesting, because I agree with so little of it. I do not believe that almost anybody can become involved in an addictive relationship with almost anything—not unless they have the genes for it. I do not believe that the genuine heart of addiction, its true root cause, is childhood abuse—although that is frequently and tragically a component of addiction, for many reasons. Overall, I see addiction as a biochemical disorder with strong behavioral attributes, mostly genetic in origin, influenced by—but not hostage to—environmental impacts, making it not so different from, say, diabetes or depression.

No doubt about it, there is a fair amount of distance between the doctor and your humble science journalist, from the nature/nurture point of view. And, students being students, they picked up on this, and wanted an explanation that would make some sense of these two seemingly opposite positions. Professor Taylor threw the question back to me:

My class was wondering how one would reconcile your and Mate’s views. Both of you discuss the addicted brain and clearly view addiction as a brain disorder. The fundamental difference is that Mate disputes the genetic component of addiction, or at least he says there is some genetic component but that the majority of the brain dysfunction and low levels of neurotransmitters found in addicted individuals relates to environmental influences during early childhood (or in the womb), rather than a genetic component…. In the book he discusses studies that indicate that insufficient maternal care, exposure to conflict etc. all lead to improper brain development which leads to increase susceptibility to addiction. So while you write about “inherited susceptibility,” he seems to favor an “environmental induced susceptibility…. Any elucidation I can share with my students would be helpful.

So. I was well and truly on the hook. I kept my response short, for the obvious reasons, but there is no getting around the fact that it’s a damn good question. Here’s what I ended up telling the class:

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Jon:

"Your students ask, quite rightly, how to reconcile the views expressed in The Chemical Carousel and In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. Or, nature vs. nurture. Dr. Maté looks to environmental impacts during early childhood as the addiction trigger, while I advocate a view of addiction as a genetic disorder, expressed because of changes in DNA, not bad mothering. (It wasn’t very long ago that schizophrenia was firmly believed to be a result of bad mothering, too!) More to the point, Maté believes, for example, that ALL female heroin addicts were sexually abused as children. That is certainly not an assertion widely agreed upon or well supported by the scientific literature. In the most recent population study of addicts and non-addicted siblings, published in Science (Feb. 3 2012), when the researchers looked at the early lives of sibling pairs, they found all the same risk factors: both the addicts and their siblings had seen roughly equal amounts of trauma in childhood. 'We really looked at their childhoods,' says Karen Ersche, lead author of the study and group leader for human addiction research at the University of Cambridge in England, quoted at Time Healthland. 'There was a lot of domestic violence, there was sexual abuse — but both [groups] had that.'

"So, which came first, the trauma, or the trauma-prone personality? Where Dr. Maté sees childhood trauma, I tend to see behavioral dysregulation. Children born with an addictive propensity also carry with them the potential for various kinds of behavioral problems, impulsivity being a common one. And it is entirely likely that most addicts have had rocky childhoods, since, quite often, they have had alcoholics in the nuclear family, with all the attendant problems, including sexual violence. Or, their own behavioral template leads to problems—angst, worry, fights, trauma. In a sense, we can say that sooner or later, something, or someone, or a series of environmental impacts, will traumatize a child with addictive propensities, in the same way that latent schizophrenia is “switched on” by a traumatic or highly emotional event. Addicts feel like outsiders from an early age, and many of them sense that something is not quite right with them, long before they ever take a drink or a drug.

"Sorting out this chicken-egg problem is a major headache. And we haven’t even discussed the possibility of trauma in the womb. But I am willing to say that none of this is as settled or as straightforward as Dr. Maté would have it. On the matter of nature/nurture, I’m willing to put the odds of that mix at 60/40, which is a good deal less genetically loaded than my estimates used to be. The growing research field of epigenetics has brought the two views closer together by demonstrating that a person’s DNA can in some cases be modified, and genes turned off and on, by environmental impacts.

"Overall, it’s safe to say that Dr. Maté and I do agree on this: One of the best defenses against the scourge of addictive disease is a stable, loving, empathetic family."

Best,

Dirk

Photo Credit: http://lofalexandria.blogspot.com/

Monday, April 22, 2013

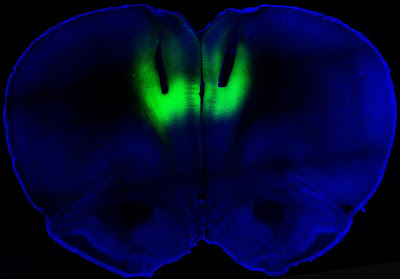

Let the Light Shine In: Addiction and Optogenetics

Study says laser light can turn cocaine addiction on and off in rats.

Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), had one word for it: “Wow.”

Writing in the director’s blog at the online NIH site, Collins said that a team of researchers from NIH and UC San Francisco had succeeded in delivering “harmless pulses of laser light to the brains of cocaine-addicted rats, blocking their desire for the narcotic.”

Wow, indeed. It didn’t take long for the science fiction technology of optogenetics to make itself felt in addiction studies. The idea of using targeted laser light to strengthen or weaken signals along neural pathways has proven surprisingly robust. The study by the NIH and the University of California at San Francisco, published in Nature, showed that lab rats engineered to carry light-activated neurons in the prefrontal cortex could be deterred from seeking cocaine. Conversely, laser light used in a way that reduced signaling in this part of the brain led previously sober rats to develop a taste for the drug. As Collins described the work:

The researchers studied rats that were chronically addicted to cocaine. Their need for the drug was so strong that they would ignore electric shocks in order to get a hit. But when those same rats received the laser light pulses, the light activated the prelimbic cortex, causing electrical activity in that brain region to surge. Remarkably, the rat’s fear of the foot shock reappeared, and assisted in deterring cocaine seeking.

All this light zapping took place in a brain region known as the prelimbic cortex. In their paper, Billy T. Chen and coworkers said that they “targeted deep-layer pyramidal prelimbic cortex neurons because they project to brain structures implicated in drug-seeking behavior, including the nucleus accumbens, dorsal striatum and amygdala.” These three subcortical regions are rich in dopamine receptors. In rats that had been challenged with foot shocks before being offered cocaine, “optogenetic prelimbic cortex stimulation significantly prevented compulsive cocaine seeking, whereas optogenetic prelimbic cortex inhibition significantly increased compulsive cocaine seeking.”

What this demonstrates is that similar regions in the human prefrontal cortex, known to regulate such actions as decision-making and inhibitory response control, may be “compromised” in addicted people. This abnormally diminished excitability in turn “impairs inhibitory control over compulsive drug seeking…. We speculate that crossing a critical threshold of prelimbic cortex hypoactivity promotes compulsive behaviors”

This all sounds vaguely unsettling; sort of a cross between phrenology and lobotomy. But it is no such thing, and the study authors believe that stimulation of the prelimbic cortex “might be clinically efficacious against compulsive seeking, with few side effects on non-compulsive reward-related behaviors in addicts.” For now, the researchers confess that they don’t know whether the reduction in cocaine seeking is caused by altered emotional conditioning, or pure cognitive processing.

Actually, nobody expects optogenetics to be used in this way with humans. The thinking is that transcranial magnetic stimulation, the controversial technique that employs noninvasive electromagnetic stimulation at various points on the scalp to alter brain behavior, would be used in place of invasive zaps with lasers. Expect to hear about clinical trials to test this theory in the near future. David Shurtleff, acting deputy director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), said in a prepared statement that the research “advances our understanding of how the recruitment, activation and the interaction among brain circuits can either restrain or increase motivation to take drugs.”

Chen B.T., Yau H.J., Hatch C., Kusumoto-Yoshida I., Cho S.L., Hopf F.W. & Bonci A. (2013). Rescuing cocaine-induced prefrontal cortex hypoactivity prevents compulsive cocaine seeking, Nature, 496 (7445) 359-362. DOI: 10.1038/nature12024

Photo credit: Billy Chen and Antonello Bonci

Thursday, April 18, 2013

On Dead Salmon, Drugs, and “Lighting Up” the Brain

Are fMRIs truly useful in addiction medicine?

What would it take to make neuroimaging a truly valuable tool for addiction medicine? Pictures of brain regions “lighting up” have always been exciting, as the early phase of neuroimaging predictably inspired rapture. Phase 2 arrived when a group of U.S. postdocs created the infamous dead salmon fMRI scan, showing that an exciting and colorful picture of false positives was entirely possible. As Neuroskeptic put it to the Globe and Mail, “Scientific journals prefer to publish results that are positive and ‘sexy,’ just like other media.”

That is nice to hear, since it takes the full blast of the heat lamp off journalists and directs it at those scientists with a habit of overamping MRI studies, even when the sample in the studies is exceedingly small. Plenty of blame to go around. Moreover, both scientists and journalists must contend with the fact that the bulk of the scientific world’s research resides behind steep pay walls—steep enough that even prestigious universities have been wailing lately about the cost of just getting one’s hands on the research reports, let along doing the research. “Media literacy in science journalism is really stunted by the fact that we don’t have access to primary sources,” said a spokesperson for the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

So much blame going around, in fact, that enthusiasm for President Obama’s recently announced brain initiative seems particularly muted among one group universally expected to rally around the project—neuroscientists themselves. Having helped to create the hype, some brain scientists are now suggesting that the only appropriate attitude is healthy skepticism about where the money will be used, and whose pockets will be picked to come up with the $100 million in kickoff funds. Rather than jumping in unison when Obama said the program would allow us to “better understand how we think and how we learn and how we remember,” skeptical neuroscientists note that “Manhattan Project”-style programs are out of fashioned in today’s distributed, system-wide landscape of experiment. “Without specific goals, hypotheses, or endpoints,” said an Emory University neuroscientist in the Globe and Mail article, “the research effort becomes a fishing expedition.”

Myself, I like to fish. But not if the pond’s too small. In a recent post at National Geographic’s blog, “Not Exactly Rocket Science,” Ed Yong quoted a neuroscientist at the University of Bristol: “If you have lots of people running studies that are too small to get a clear answer, that’s more wasteful in the long-term.”

Exactly so, and one might think that a large, coordinated, possibly international initiative at studying the architecture and function of the human brain might serve as a powerful antidote to a micro-universe of tiny studies and insignificant findings.

But forget the big and little pictures for a moment. Let’s focus on what’s in it for addiction studies. What would have to happen—how would fMRIs, PETs and EEGs have to be used in order to advance our understanding of drug and alcohol abuse?

In a recent editorial —“What neuroimaging has and has not yet added to our understanding of addiction”—Martina Reske of the Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine in Julich, Germany, argues that we must take “three critical steps to implement neuroimaging as a new basis for diagnostics and treatment of substance use disorders: first, we need to merge diverse imaging findings into one comprehensive brain imaging perspective of addiction. Next, we need to identify prediction algorithms for individual substance users.” And finally, Reske writes in Addiction, “The ultimate goal has to be the development of treatment regimens based on neuroimaging results.” The interested lay public may be forgiven for assuming that all three of these conditions were already being met.

Specifically, Reske argues for “multi-modal approaches to overcome technological shortcomings. Simultaneous EEG-fMRI, for instance, combines high temporal and spatial resolution of exactly the same mental process, and hybrid MR-PET imaging allows for functional/structural and molecular characterizations.” What might stand in the way of such solutions, you ask? Reske answers that it is likely to be “the existing researchers’ hesitation, unwillingness or inability to consolidate findings from different imaging modalities.” In this case, she suggests, it is the scientists themselves, perhaps overly protective of individual turfs and research fiefdoms, who are hemming and hawing about large-scale collaborative efforts.

To reach a level of clinical relevance for addiction, neuroimaging must be used to delineate and identify “occasional versus habitual versus compulsive use or intoxication versus abstinence versus relapse.” These are not things that existing neuroimagery can do for us, but Reske believes one promising avenue will be the identification of subjects with an abnormally high risk for relapse, something neither patients nor therapists are very good at predicting. (This immediately brings neuroimaging up against a ripe field of ethical questions having to do with the identification and disclosure of high-risk subjects.)

What other payoffs might there be? Reske can think of a few: “First, linkage of neuroimaging and pharmacological studies will prove useful for predicting response to medication. Secondly, knowledge of the biological differences between responders and non-responders to available treatments might facilitate identification of the best-suited therapy for that particular individual. Thirdly, understanding which brain regions show alterations in functioning should spur the development of specific medications, cognitive-behavioral or neuroimaging-based trainings that target optimal activation levels in these regions.”

Neuroimaging is not yet specific or sensitive enough, and its practitioners not yet practiced enough, to accomplish these tasks except in a tantalizingly patchwork fashion. Neuroimaging-based predictions of addiction liability and damage and relapse make up an infant science, ripe for both growth and abuse. Obviously, it will take the gold standard of longitudinal studies involving enormous samples of participants, who would ideally be followed and scanned for decades. But such studies are, as Reske reminds us, “methodologically challenging, expensive and not promising in terms of short-term publication of results.” It sounds like the kind of Big Project that might fit under the umbrella of, say, a major, well-funded, multi-year brain research initiative endorsed by the President of the United States….

Photo Credit: https://docs.uabgrid.uab.edu/

Labels:

addiction brain scan,

brain scans,

fmri,

MRI scan,

MRI studies,

neuroimaging,

PET scans

Sunday, April 14, 2013

Marijuana and the Gateway Hypothesis

Smoke pot, shoot smack?

The Great Gateway Hypothesis has had a long, controversial run as a central tenet of American anti-drug campaigns. As put forth by Denise B. Kandell of Columbia University and others in 1975, and refined and redefined ever since, the gateway theory essentially posits that soft drugs like alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana—particularly marijuana—make users more likely to graduate to hard drugs like cocaine and heroin. What is implied is that gateway drugs cause users to move to harder drugs, by some unknown mechanism. The gateway theory forms part of the backbone of the War on Drugs. By staying tough on marijuana use, policy makers believe they will have much broader impacts on hard drug use down the road.

This notion is virtually an article of faith in the drug prevention community. It just feels intuitively right: Scratch a junkie, and you’ll find a younger, embryonic pot smoker or furtive teenage drinker. Ergo, prevent teen pot smoking, and you will block the blossoming of a multitude of future hard drug addicts.

For years, the gateway hypothesis has had its share of contentious opponents. The countervailing theory is known primarily as CLA, for Common Liability to Addiction, the genetically based approach that lines up with the notion of addiction as a chronic disease entity. Most genetic association studies have failed to record risk variations for addiction that are specific to one addictive drug. Writing last year in Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Michael M. Vanyukov of the University of Pittsburgh, along with a large group of prominent addiction researchers, argued that the gateway hypothesis is essentially a form of circular reasoning. “It is drug use itself that is viewed as the cause of drug use development,” they write. The staged progression from one drug to another “is defined in a circular manner: a stage is said to be reached when a certain drug is used, but this drug is supposed to be used only upon reaching this stage. In other words, the stage both is identified by the drug and identifies the drug. In effect, the drug is identical to the stage.”

The researchers reject any causal claims on behalf of the gateway hypothesis and insist there is no necessary usage of soft drugs at an earlier stage to pave the way for hardcore addiction, however watertight the idea might sound. The high correlations are “artifactual,” they argue, “because they are estimated among hard drug users, without taking into account the large population of those who try or even habitually use marijuana but never transition to harder drugs.” A common cause, such as an underlying vulnerability to all drugs of abuse, seems more to the point, they insist. There is nothing out there to suggest that “these stages are either obligatory or universal, nor that all persons must progress through each in turn… the initiation order is frequently reversed even for the licit-to-illicit sequence.” There is only one stage that universally precedes hard drug use, they argue. And that is non-use. “It is the non-use then, which should be the actual gateway condition.”

The leading theory supporting the gateway hypothesis is that some as yet undetermined mechanism of “sensitization” occurs after using a gateway drug. But there is no science supporting this notion. “If sensitization does occur,” the researchers say, “it is equivalent to an increase in individual liability at the level of neurochemical mechanisms of addiction.”

The paper in Drug and Alcohol Dependence notes that in Japan, where marijuana is used by less than 5 percent of young people, “cannabis is not used first by a staggering 83.2% of the users of other illicit drugs, thus violating the gateway sequence.” Japan also handily knocks down the idea of alcohol as a gateway drug: Whereas the prevalence of aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency—the so-called alcohol flush reaction—keeps many Asians from drinking alcohol regularly, this does not correlate with lower rates of non-alcohol substance use in that population.

All of this would seem to put the last nail in the notion that “involvement in various classes of drugs is not opportunistic but follows definite pathways,” as Vanyukov et. al. put it. Common sense seems to be ahead of official drug policy in this regard. According to Maia Szalavitz, writing at TimeHealthland, “only 38% of people now agree with the idea that ‘for most people, the use of marijuana leads to the use of hard drugs’ compared to 60% in 1977.”

For proponents of common liability to addiction models, any staged sequencing of drug use is considered opportunistic and trivial. Which, interestingly, is how many addicts tend to view the gateway theory. But the idea of marijuana or alcohol as a gateway drug just feels intuitively correct to many people. Part of the problem is chronological. “At the relatively distal time when genetic relationships are usually evaluated,” the authors maintain, “the role of this early-acting factor may be as difficult to detect as it is to find a match that started a forest fire.” Your genetic endowment is with you from birth, while your first drink or toke of marijuana does not happen for a decade or two. Individual environmental conditions, from epigenetic changes to a move to a different neighborhood, determine how it will play out down the road, but these factors are mostly invisible at the time of addiction.

All of this matters from a policy point of view, because research “may be hindered or misdirected if a concept lacking substance, validity and utility is accorded prominence.” However, even when the gateway hypothesis is taken as a given, different legal and social outcomes are still possible. The best example is found in The Netherlands. The prevailing belief there is that “the pharmacological effects of cannabis increase adolescents’ likelihood of using other drugs,” as stated by Wayne Hall, a professor of public health policy at the University of Queensland, Australia. Writing in Addiction, Hall says that drug policy analysts in The Netherlands have argued that the fabled gateway “is a consequence of the fact that cannabis and other illicit drugs are sold in the same black market; they have advocated for the decriminalization of cannabis use and small retail sales in order to break the nexus between cannabis use and the use of other illicit drugs.”

This “Marijuana Shop” approach may have direct relevance in the U.S., in the wake of cannabis legalization in Washington and Colorado. James Anthony, a professor of epidemiology at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins, writes about the real-world ramifications of the cannabis shop in Addiction: “Do we actually achieve a near-term delay in the time to a young person’s first chance to try cocaine or heroin... [or] do we run the risk of accumulating more cases of dependence on marijuana, or other hazards attributable to non-essential marijuana use?

The true gateways to addiction appear to be behavioral. As part of their genetic endowment, budding addicts are far more likely than other people to exhibit behavioral “dysregulation” when young, in the form of disinhibition, impulsivity, and antisocial behaviors. More than half of all addicts are co-morbid, meaning they also have a psychological or behavioral disorder in addition to addiction. Further analysis of this fact would seem to be a more fruitful research avenue than simply prodding at alcohol or marijuana in an effort to uncover their chemical “secrets” for compelling future drug use.

Photo Credit: http://tcktcktck.org/ Creative Commons: Randi Shooters, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)