Showing posts with label cocaine research. Show all posts

Showing posts with label cocaine research. Show all posts

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Crack Babies Are Turning Out Okay

Major study concludes that crack panic was overblown.

In an excellent story for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Susan FitzGerald traces the fortunes of Philadelphia children enrolled in a study that began in 1989, at the height of the crack “epidemic” in the U.S. Headed up by Hallam Hurt, then the chair of neonatology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, a group began the in-vitro study of babies exposed to maternal crack cocaine use. One of the longest-running studies of its kind, the NIDA-funded research on 224 babies born between 1989 and 1992, half of them cocaine-exposed, the other half normal controls, was now coming to a close. And the results were not what most people were expecting.

In the Inquirer article, Hurt notes that cocaine can in fact trigger premature labor, raise blood pressure, and risk a condition in which the placenta breaks loose from the uterine wall. So it was natural to go looking for long-term effects in all of those twitching, underweight newborn crack babies viewers saw on television. Physicians warned that damage to developing dopamine systems would result in long-term or permanent impairments in attention, language, and memory. So Hurt and colleagues went looking—and couldn’t find them. Neither could researchers at other institutions. Said Hurt: “We began to ask, ‘Was there something else going on?’”

As FitzGerald writes: “The years of tracking kids have led Hurt to a conclusion she didn’t see coming. ‘Poverty is a more powerful influence on the outcome of inner-city children than gestational exposure to cocaine,'" Hurt said. For example, babies born to mothers on heroin or methadone will have certain characteristic withdrawal symptoms, which can be managed by informed hospital staff. The same is true with newborns whose mothers have been using crack. In most cases, these withdrawals can be managed without permanent harm to the infant.

In a paper authored by Hurt, Laura M Betancourt, and others, the investigators write: “It is now well established that gestational cocaine exposure has not produced the profound deficits anticipated in the 1980s and 1990s, with children described variably as joyless, microcephalic, or unmanageable.” The authors do not rule out “subtle deficits,” but do not find evidence for them in functional outcomes like school or transition to adulthood.

How did this urban legend get started? In the 1980s, during the Reagan-Bush years, Americans were confronted with yet another drug “epidemic.” The resulting media fixation on crack provided a fascinating look at what has been called “drug education abuse.” This new drug war took off in earnest after Congress and the media discovered that an inexpensive, smokable form of cocaine was appearing in prodigious quantities in some of America’s larger cities. Crack was a refinement to freebasing, and a drug dealer’s dream. The “rush” from smoking crack was more potent, but even more transient, than the short-lived high from nasal ingestion.

Coupled with this development were the cocaine-related deaths of two well-known athletes, college basketball star Len Bias and defensive back Don Rogers of the Cleveland Browns. Bias played for Maryland, a home team in Washington, D.C. Six months earlier, Reagan had brought the military into the drug wars in a major way. The initial test of the directive was Operation Blast Furnace, a no-holds-barred attack on cocaine laboratories in the jungles of Bolivia.

As I wrote in 2008 in The Chemical Carousel:

The death of Len Bias elevated cocaine paranoia to the realm of the mythic. Cocaine became America’s first living-room drug, courtesy of the nightly news. The summer of 1986 will be remembered as the season of the “crack plague,” as viewers were bombarded with long news stories and specials. NBC Nightly News offered a special report on crack, during which a correspondent told viewers: “Crack has become America’s drug of choice... it’s flooding America....”

The hyperkinetic level of television coverage ultimately led TV Guide Magazine to commission a report from the News Study Group, headed by Edwin Diamond at New York University. The investigators quickly demolished the notion that cocaine had become America’s “drug of choice,” and were at a loss to account for where the networks had come up with it: “Statistically, alcohol and tobacco are the legal ‘drugs of choice’: 53 million people smoke cigarettes; 17.6 million are dependent on alcohol or abuse it. Marijuana still ranks as the No. 1 illegal drug. According to NIDA, 61.9 million people in the United States have experimented with marijuana.” The study group went on to note that the often-deadly “Black Tar” heroin had hit the streets of American cities the same summer. “Why was crack a big story [that summer] while Black Tar was not? One reason [is that] crack is depicted as moving into ‘our’—that is, the comfortable TV viewers’—neighborhood.”

Monday, April 22, 2013

Let the Light Shine In: Addiction and Optogenetics

Study says laser light can turn cocaine addiction on and off in rats.

Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), had one word for it: “Wow.”

Writing in the director’s blog at the online NIH site, Collins said that a team of researchers from NIH and UC San Francisco had succeeded in delivering “harmless pulses of laser light to the brains of cocaine-addicted rats, blocking their desire for the narcotic.”

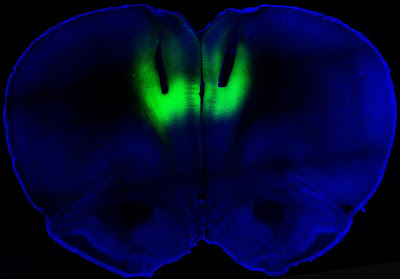

Wow, indeed. It didn’t take long for the science fiction technology of optogenetics to make itself felt in addiction studies. The idea of using targeted laser light to strengthen or weaken signals along neural pathways has proven surprisingly robust. The study by the NIH and the University of California at San Francisco, published in Nature, showed that lab rats engineered to carry light-activated neurons in the prefrontal cortex could be deterred from seeking cocaine. Conversely, laser light used in a way that reduced signaling in this part of the brain led previously sober rats to develop a taste for the drug. As Collins described the work:

The researchers studied rats that were chronically addicted to cocaine. Their need for the drug was so strong that they would ignore electric shocks in order to get a hit. But when those same rats received the laser light pulses, the light activated the prelimbic cortex, causing electrical activity in that brain region to surge. Remarkably, the rat’s fear of the foot shock reappeared, and assisted in deterring cocaine seeking.

All this light zapping took place in a brain region known as the prelimbic cortex. In their paper, Billy T. Chen and coworkers said that they “targeted deep-layer pyramidal prelimbic cortex neurons because they project to brain structures implicated in drug-seeking behavior, including the nucleus accumbens, dorsal striatum and amygdala.” These three subcortical regions are rich in dopamine receptors. In rats that had been challenged with foot shocks before being offered cocaine, “optogenetic prelimbic cortex stimulation significantly prevented compulsive cocaine seeking, whereas optogenetic prelimbic cortex inhibition significantly increased compulsive cocaine seeking.”

What this demonstrates is that similar regions in the human prefrontal cortex, known to regulate such actions as decision-making and inhibitory response control, may be “compromised” in addicted people. This abnormally diminished excitability in turn “impairs inhibitory control over compulsive drug seeking…. We speculate that crossing a critical threshold of prelimbic cortex hypoactivity promotes compulsive behaviors”

This all sounds vaguely unsettling; sort of a cross between phrenology and lobotomy. But it is no such thing, and the study authors believe that stimulation of the prelimbic cortex “might be clinically efficacious against compulsive seeking, with few side effects on non-compulsive reward-related behaviors in addicts.” For now, the researchers confess that they don’t know whether the reduction in cocaine seeking is caused by altered emotional conditioning, or pure cognitive processing.

Actually, nobody expects optogenetics to be used in this way with humans. The thinking is that transcranial magnetic stimulation, the controversial technique that employs noninvasive electromagnetic stimulation at various points on the scalp to alter brain behavior, would be used in place of invasive zaps with lasers. Expect to hear about clinical trials to test this theory in the near future. David Shurtleff, acting deputy director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), said in a prepared statement that the research “advances our understanding of how the recruitment, activation and the interaction among brain circuits can either restrain or increase motivation to take drugs.”

Chen B.T., Yau H.J., Hatch C., Kusumoto-Yoshida I., Cho S.L., Hopf F.W. & Bonci A. (2013). Rescuing cocaine-induced prefrontal cortex hypoactivity prevents compulsive cocaine seeking, Nature, 496 (7445) 359-362. DOI: 10.1038/nature12024

Photo credit: Billy Chen and Antonello Bonci

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)