Showing posts with label coffee addiction. Show all posts

Showing posts with label coffee addiction. Show all posts

Thursday, September 17, 2015

Caffeine, Energy Drinks, and Everything Else

A couple of years ago, coffee drinkers were buoyed by the release of a massive study in the New England Journal of Medicine that “did not support a positive association between coffee drinking and mortality.” In fact, the analysis by Neal D. Freedman and associates showed that even at the level of 6 or more cups per day, coffee consumption appeared to be mildly protective against diabetes, stroke, and death due to inflammatory diseases. Men who drank that much coffee had a 10% lower risk of death, and women in this category show a 15% lower death risk. Coffee, it seemed, was good for you.

Hooray for coffee—but lost in the general joy over the findings was the constant association of coffee with unhealthy behaviors like smoking, heavy alcohol, use, and consumption of red meat. And the happy coffee findings did not consider the consumption of caffeine in other forms, such as energy drinks, stay-awake pills, various foodstuffs, and even shampoos.

One of the earliest battles over “energy drinks” was an action taken in 1911 under the new Pure Food and Drug Act—the seizure by government agents of 40 kegs and 20 barrels of Coca-Cola syrup in Chattanooga. Led by chemist Harvey Wiley, the first administrator of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), agents of the fledgling organization acted on the belief that the soft drink contained enough caffeine to pose a significant public health hazard. The court case went on forever. Eventually Coca-Cola cut back on caffeine content, and the charges were dropped.

Jump cut to 2012, and watch the FDA grapple with the same question a hundred years later, citing concerns about undocumented caffeine levels in so-called energy drinks in the wake of an alleged link between the caffeinated soft drinks and the death of several young people. According to Dr. Kent Sepkowitz, writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association, while only 6% of young American men consume the drinks, “in a recent survey of U.S. overseas troops, 45% reported daily use.” In 2006, more than 500 new energy drinks hit the market. By 2011, sales of energy drinks in the U.S. climbed by more than 15% to almost $9 billion.

Death by caffeine has long been a subject of morbid interest, and an article in the Journal of Caffeine Research by Jack E. James of Iceland’s Reykjavik University questions these prevailing assumptions, and brings together the latest research on this perennial question, including, yes, a consideration of whether the time has come to regulate caffeine as some sort of controlled substance.

In 2013, the FDA released reports that attributed a total of 18 deaths to energy drinks. Somewhere between 3 and 10 grams of caffeine will kill you, especially if you are young, old, or suffer from various health problems. The generally accepted lethal dose is 10 g. The wide gap in estimates and mortality reports reflects the wide variation in caffeine’s effects. Half the lethal dose can kill a child, and some adults have survived 10 times that amount. As I wrote in an earlier post (“Energy Drinks: What’s the Big Deal?”): “Energy drinks are safe—if you don’t guzzle several of them in a row or substitute them for dinner, or have diabetes, or an ulcer, or happen to be pregnant, or are suffering from hearth disease or hypertension. And if you do OD on high caffeine intake, it will not be pleasant: Severe cardiac arrhythmias, palpitations, panic, mania, muscle spasms, and seizures.”

Warning signs include racing heart, abdominal pain, vomiting, and agitation. Since the average cup of coffee weighs in at about 100 milligrams, there doesn’t seem to be much to worry about in that regard. Nonetheless, the American National Poison Data System (NPDS) has more than 6,000 “case mentions” related to caffeine. One of these cases generated considerable press coverage: the death of a 14 year-old girl with an inherited connective tissue disorder.

In his article for the Journal of Caffeine Research, James starts by noting other fatalities, including two confirmed caffeine-related deaths in New Mexico, and four in Sweden, among other long-standing historical reports. Still, not much there to wring your hands over—but James insists that data on poisonings “do not show what contributory role caffeine may have had in cases where fatal and near-fatal outcomes were deemed to have been due to other compounds also present.”

Fair enough. But here is where the argument gets interesting. “Considerably smaller amounts of caffeine,” writes James, "may be fatal under a variety of atypical though not necessarily rare circumstances.” Among these, he singles out: 1) Prior medical conditions predisposing patients toward unusual caffeine metabolism. 2) Unknown interactions and synergies with prescription, over-the-counter, and illegal drugs. 3) Physical stress and high-intensity sports. 4) Children, for whom caffeine is easily available.

James claims we don’t know enough to insist caffeine is essentially harmless, let along good for us in large doses. He compiled this eye-opening list of foods and other products that sometimes contain caffeine: ice cream, chewing gum, yogurt, breakfast cereal, cookies, flavored milk, beef jerky, cold and flu medications, weight-loss compounds, breath-freshener sprays and mints, skin lotion, lip balm, soap, shampoo, and, most notably, as a contaminant in illegal drugs. James says that the largest category of incidents with over-caffeinated young people involve “miscellaneous stimulants and street drugs…”

As for energy drinks themselves: “As a nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist, caffeine counteracts the somnogenic effects of acute alcohol intoxication, and alcohol may in turn ameliorate the anxiogenic effects of caffeine.” It’s an age-old practice: caffeine doesn’t sober up drunks, but it does keep them awake. James believes the evidence shows that the combination of caffeine and alcohol increases the risks of unprotected sex, sexual assault, drunk driving, violence, and emergency room visits.

Furthermore, “the ubiquity of caffeine is such that it has become a biologically significant contaminant of freshwater and marine systems….”

Finally, James offers a vision of a caffeine-regulated future, noting that Denmark, France, and Norway have already introduced sales restrictions on energy drinks. Restrictions on the sale of powdered caffeine may follow, as a valid public health measure. “Canada requires labeling in relation to the same product, advising that it should not be mixed with alcohol.” Other countries have labeled energy drinks as “high caffeine content” beverages. And Sweden regulates the number of caffeine tablets that can be purchased at one time from a drugstore. Meanwhile, in the U.S., makers of energy drinks, unlike makers of soft drinks, do not even have to print the amount of caffeine on the label as dietary information, although this is in the process of changing. Major energy drink makers are moving to put caffeine content labels on their products, in part to shift their relationship with the FDA. Last year, The Food and Drug Administration advised consumers to avoid powdered caffeine due to health risks.

Originally published March 13, 2013

Graphics: http://www.runnersworld.com

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

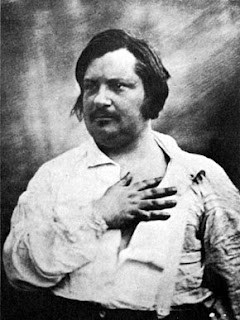

From “The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee”

By Honore de Balzac, translated by Robert Onopa.

Coffee is a great power in my life; I have observed its effects on an epic scale….

Coffee affects the diaphragm and the plexus of the stomach, from which it reaches the brain by barely perceptible radiations that escape complete analysis; that aside, we may surmise that our primary nervous flux conducts an electricity emitted by coffee when we drink it. Coffee's power changes over time. [Italian composer Gioacchino] Rossini has personally experienced some of these effects as, of course, have I. "Coffee," Rossini told me, "is an affair of fifteen or twenty days; just the right amount of time, fortunately, to write an opera." This is true. But the length of time during which one can enjoy the benefits of coffee can be extended.

For a while - for a week or two at most - you can obtain the right amount of stimulation with one, then two cups of coffee brewed from beans that have been crushed with gradually increasing force and infused with hot water.

For another week, by decreasing the amount of water used, by pulverizing the coffee even more finely, and by infusing the grounds with cold water, you can continue to obtain the same cerebral power.

When you have produced the finest grind with the least water possible, you double the dose by drinking two cups at a time; particularly vigorous constitutions can tolerate three cups. In this manner one can continue working for several more days....

Finally, I have discovered a horrible, rather brutal method that I recommend only to men of excessive vigor... It is a question of using finely pulverized, dense coffee, cold and anhydrous, consumed on an empty stomach. This coffee falls into your stomach, a sack whose velvety interior is lined with tapestries of suckers and papillae. The coffee finds nothing else in the sack, and so it attacks these delicate and voluptuous linings; it acts like a food and demands digestive juices; it wrings and twists the stomach for these juices, appealing as a pythoness appeals to her god; it brutalizes these beautiful stomach linings as a wagon master abuses ponies; the plexus becomes inflamed; sparks shoot all the way up to the brain. From that moment on, everything becomes agitated. Ideas quick-march into motion like battalions of a grand army to its legendary fighting ground, and the battle rages. Memories charge in, bright flags on high; the cavalry of metaphor deploys with a magnificent gallop; the artillery of logic rushes up with clattering wagons and cartridges; on imagination's orders, sharpshooters sight and fire; forms and shapes and characters rear up; the paper is spread with ink - for the nightly labor begins and ends with torrents of this black water, as a battle opens and concludes with black powder.

I recommended this way of drinking coffee to a friend of mine, who absolutely wanted to finish a job promised for the next day: he thought he'd been poisoned and took to his bed, which he guarded like a married man. He was tall, blond, slender and had thinning hair; he apparently had a stomach of papier-mache. There has been, on my part, a failure of observation…."

Labels:

Balzac,

caffeine,

caffeine overdose,

coffee,

coffee addiction,

coffee overdose

Wednesday, March 13, 2013

Dying For Caffeine

It’s not the coffee, it’s everything else.

Late last year, coffee drinkers were buoyed by the release of a massive study in the New England Journal of Medicine that “did not support a positive association between coffee drinking and mortality.” In fact, the analysis by Neal D. Freedman and associates showed that even at the level of 6 or more cups per day, coffee consumption appeared to be mildly protective against diabetes, stroke, and death due to inflammatory diseases. Men who drank that much coffee had a 10% lower risk of death, and women in this category show a 15% lower death risk. Coffee, it seemed, was good for you.

Hooray for coffee—but lost in the general joy over the findings was the constant association of coffee with unhealthy behaviors like smoking, heavy alcohol, use, and consumption of red meat. And the happy coffee findings did not consider the consumption of caffeine in other forms, such as energy drinks, stay-awake pills, various foodstuffs, and even shampoos.

One of the earliest battles over “energy drinks” was an action taken in 1911 under the new Pure Food and Drug Act—the seizure by government agents of 40 kegs and 20 barrels of Coca-Cola syrup in Chattanooga. Led by chemist Harvey Wiley, the first administrator of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), agents of the fledgling organization acted on the belief that the soft drink contained enough caffeine to pose a significant public health hazard. The court case went on forever. Eventually Coca-Cola cut back on caffeine content, and the charges were dropped.

Jump cut to 2012, and watch the FDA grapple with the same question a hundred years later, citing concerns about undocumented caffeine levels in so-called energy drinks in the wake of an alleged link between the caffeinated soft drinks and the death of several young people. According to Dr. Kent Sepkowitz, writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association, while only 6% of young American men consume the drinks, “in a recent survey of U.S. overseas troops, 45% reported daily use.” In 2006, more than 500 new energy drinks hit the market. By 2011, sales of energy drinks in the U.S. climbed by more than 15% to almost $9 billion.

Death by caffeine has long been a subject of morbid interest, and a recent article in the Journal of Caffeine Research by Jack E. James of Iceland’s Reykjavik University questions these prevailing assumptions, and brings together the latest research on this perennial question, including, yes, a consideration of whether the time has come to regulate caffeine as some sort of controlled substance.

Last month, the FDA released reports that attributed a total of 18 deaths to energy drinks. Somewhere between 3 and 10 grams of coffee will kill you, especially if you are young, old, or suffer from various health problems. The generally accepted lethal dose is 10 g. The wide gap in estimates and mortality reports reflects the wide variation in caffeine’s effects. Half the lethal dose can kill a child, and some adults have survived 10 times that amount. As I wrote in an earlier post (“Energy Drinks: What’s the Big Deal?”): “Energy drinks are safe—if you don’t guzzle several of them in a row or substitute them for dinner, or have diabetes, or an ulcer, or happen to be pregnant, or are suffering from hearth disease or hypertension. And if you do OD on high caffeine intake, it will not be pleasant: Severe cardiac arrhythmias, palpitations, panic, mania, muscle spasms, and seizures.”

Warning signs include racing heart, abdominal pain, vomiting, and agitation. Since the average cup of coffee weighs in at about 100 milligrams, there doesn’t seem to be much to worry about in that regard. Nonetheless, the American National Poison Data System (NPDS) has more than 6,000 “case mentions” related to caffeine. One of these cases generated considerable press coverage: the death of a 14 year-old girl with an inherited connective tissue disorder.

In his article for the Journal of Caffeine Research, James starts by noting other fatalities, including two confirmed caffeine-related deaths in New Mexico, and four in Sweden, among other long-standing historical reports. Still, not much there to wring your hands over—but James insists that data on poisonings “do not show what contributory role caffeine may have had in cases where fatal and near-fatal outcomes were deemed to have been due to other compounds also present.”

Fair enough. But here is where the argument gets interesting. “Considerably smaller amounts of caffeine,” writes James, "may be fatal under a variety of atypical though not necessarily rare circumstances.” Among these, he singles out: 1) Prior medical conditions predisposing patients toward unusual caffeine metabolism. 2) Unknown interactions and synergies with prescription, over-the-counter, and illegal drugs. 3) Physical stress and high-intensity sports. 4) Children, for whom caffeine is easily available.

James claims we don’t know enough to insist caffeine is essentially harmless, let along good for us in large doses. He compiled this eye-opening list of foods and other products that sometimes contain caffeine: ice cream, chewing gum, yogurt, breakfast cereal, cookies, flavored milk, beef jerky, cold and flu medications, weight-loss compounds, breath-freshener sprays and mints, skin lotion, lip balm, soap, shampoo, and, most notably, as a contaminant in illegal drugs. James says that the largest category of incidents with over-caffeinated young people involve “miscellaneous stimulants and street drugs…”

As for energy drinks themselves: “As a nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist, caffeine counteracts the somnogenic effects of acute alcohol intoxication, and alcohol may in turn ameliorate the anxiogenic effects of caffeine.” It’s an age-old practice: caffeine doesn’t sober up drunks, but it does keep them awake. James believes the evidence shows that the combination of caffeine and alcohol increases the risks of unprotected sex, sexual assault, drunk driving, violence, and emergency room visits.

Furthermore, “the ubiquity of caffeine is such that it has become a biologically significant contaminant of freshwater and marine systems….”

Finally, James offers a vision of a caffeine-regulated future, noting that Denmark, France, and Norway have already introduced sales restrictions on energy drinks. “Canada requires labeling in relation to the same product, advising that it should not be mixed with alcohol.” Other countries have labeled energy drinks as “high caffeine content” beverages. And Sweden regulates the number of caffeine tablets that can be purchased at one time from a drugstore. Meanwhile, in the U.S., makers of energy drinks, unlike makers of soft drinks, do not even have to print the amount of caffeine on the label as dietary information, although this is in the process of changing. Major energy drink makers are moving to put caffeine content labels on their products, in part to shift their relationship with the FDA.

Bonus: Check HERE for the 15 most caffeinated cities in America. Sure, Seattle is first, but can you guess the others?

Graphics credit: Wikipedia

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

The Addiction Inbox Top Ten

What are readers of Addiction Inbox interested in? Although scarcely scientific, a look at the most-viewed posts here over the past couple of years is indicative of general interest—or at least indicative of the general drift of Google searches on topics related to addiction and drugs.

Ranked by overall page views, from most to least, here are the ten most-visited blog posts on Addiction Inbox:

The most popular post on Addicton Inbox by a considerable margin. With almost 700 reader comments, this post has evolved into a message board for people having problems related to marijuana dependence and withdrawal. Very interesting first-person stuff attached to a rather straightforward post. Continues to grow like Topsy.

A continuation of the discussion of marijuana withdrawal, or, as the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Nora Volkow calls it, “cannabis withdrawal syndrome.” 100 reader comments thus far.

Sometimes you just gotta get back to basics. Inquiring readers want to know.

A lively debate on the new, smokeless nicotine delivery system. Electronic cigarettes use batteries to convert liquid nicotine into a heated mist that is absorbed by the lungs. The latest in harm reduction strategies, or starter kits for youngsters?

Another good response to a medical post about a drug for seizure disorders and migraines that shows promise as an anti-craving drug for alcoholism. People are getting more accustomed to hearing about medications for addiction.

Not a big surprise.

Another comment-heavy post concerning a controversial study of withdrawal effects from smoking cigarettes and pot.

Something of a merger here between two consistently popular topics--cannabis and brain science. After the Sanskrit “ananda,” meaning bliss.

Readers seem to take seriously the notion that certain forms of overeating are substance addictions. This post focused on sugar's drug-like effect on the nucleus accumbens, a dopamine-rich brain structure in the limbic system.

10. Coffee Addiction

Increased tolerance, craving, and verifiable withdrawal symptoms--the primary determinants of addiction--are easily demonstrated in victims of caffeinism.

Sunday, July 12, 2009

Stimulating Facts About Caffeine

Coffee highs and lows.

[Excerpted from “Caffeine: Pharmacology and Effects of the World’s Most Popular Drug,” by Kyle M. Clayton and Paula Lundberg-Love, in The Praeger International Collection on Addictions Volume 2]:

-- Caffeine dependence is not presently recognized as a clinical disorder in the American Psychological Association’s DSM-IV-TR. Caffeine intoxication, however, is listed as a distinct clinical syndrome. Most of the symptoms of caffeine intoxication resemble symptoms of cocaine or amphetamine overdose: anxiety, insomnia, restlessness, tremor, irritability, rambling speech patterns, and irregular heartbeat. “In adult cases of highly elevated doses,” the authors write, “symptoms such as fever, hallucinations, delusions and loss of consciousness have occurred.”

--In high enough doses, caffeine is extremely toxic and can lead to death. The good news: This almost never happens, since the potentially lethal dose is on the order of 50 to 100 cups of coffee, quickly consumed. There is, however, the theoretical risk that an overdose of caffeine tablets could be fatal.

--Caffeine tolerance develops in a hurry. Tolerance to the sleep-disrupting effects of coffee in high doses can occur after only seven days of consuming 400 mg of caffeine three times a day—using 120 mg per cup as a rough average, that amounts to about ten cups of strong coffee per day. The researchers report that “complete tolerance to subjective effects such as nervousness, tension, jitters and elevated energy were observed to develop after consuming 300 mg three times per day for 18 days, and it is possible that such tolerance can occur within a shorter period of time.”

--Caffeine can interfere with the effectiveness of benzodiazepines and other medications that act on the neurotransmitter GABA. “Caffeine can inhibit the binding of benzodiazepines to their specific receptors on the GABA-A receptor sites, therefore neutralizing the effects of such medications and inhibiting their sedative hypnotic effects. Such interactions should be considered when evaluating the effectiveness of medications used to treat insomnia.”

--Conversely, caffeine can enhance the effectiveness of pain relievers. In particular, caffeine allows for faster absorption of headache medications, producing faster relieve at lower doses. Nicotine increases the rate at which the body metabolizes caffeine. Abstinent cigarette smokers often discover that their usual intake of coffee causes jitters and a bad stomach once they quit smoking. Some researchers have speculated that a high level of caffeine intake during smoking cessation might cause an increase in nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

Photo Credit: www.healingwithnutrion.com

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

Ten Ways to Battle Coffee Addiction

Caffeine-free energy boosters

(From the mailbag)

Kelly Sonora at the Nursing Online Education Database (NOEDb) recently sent me an article by Christina Laun, entitled "50 Ways to Boost Your Energy Without Caffeine." The complete article is available on the NOEDb web site. If you are making an effort to decrease reliance on coffee, Laun writes, the suggestions will "give you a boost when you're feeling sleepy or prevent tiredness altogether."

Herewith, a sampling:

--Turn on the lights. Your body responds naturally to changes in light, so if it's unnaturally dark where you're working or sleeping it may make staying alert a lot harder. Try keeping your blinds open a bit so you'll wake up naturally in the morning or adding a few extra lights to your workspace to keep you from feeling sleepy throughout the day.

--Examine your emotions. Stress, depression and other negative emotions can take a heavy toll on your energy levels. Your exhaustion may have a lot to do with how you're feeling mentally, so take the time to deal with your emotions or get help if you need it.

--Don't linger in bed. Hitting the snooze button in the morning may delay the inevitable time when you do have to get up, but it's not doing you any favors in the long run. Challenge yourself to get up and move around for at least 10 minutes to see if you're still super tired. Chances are, once you get up you'll be ready to start your day.

--Eat smaller, more frequent meals. Eating meals that are infrequent can cause your blood glucose to spike and crash, leaving you tired and hungry. And digesting huge meals can steal energy you need for other things. Instead, eat smaller meals throughout the day so you can keep your energy level and keep yourself feeling great.

-- Cut down on alcohol. Alcohol may appear to make you sleepy, but it can actually ensure that you get a much lower quality of sleep than you would otherwise. Keep it in moderation so it won't affect your sleep and make you groggy the next day.

--Get out of the house. Sunlight can help wake you up and help you stay up, so take a trip outside to catch some rays and get some fresh air.

--Get away from your desk. Hours upon hours of sitting at your desk can start to sap your energy and make you plead for it to be 5 o'clock already. Give yourself a quick pick-me-up by stepping away from your desk for a bit for a trip to the water fountain, a walk around the office or just a short break.

--Listen to your favorite up-tempo songs. If you can listen to music at work, why not put on some tunes that will get your heart pumping and make you want to dance? It's a surefire way to beat the mid-afternoon slump.

--Stop slouching. Slumping down at your desk isn't doing you any favors in the alertness category. Sitting up at your desk, in an ergonomically friendly way, can make you feel more alert and ready to work.

--Avoid coworkers who sap your energy. Everyone has that one coworker who is so glum, negative or boring that they just suck the energy right out of you. When it's possible, keep this person away from you to save your energy and maybe your sanity too.

Friday, May 9, 2008

Coffee Addiction

The pharmacology of caffeine

Recent studies have documented the existence of severe caffeine addicts who suffer significant depression and lessened cognitive capacity for several weeks or months following termination of coffee drinking. Balzac, the nineteenth century French writer, reportedly died of caffeine poisoning at roughly the 50-cup-per-day level.

At low doses, caffeine sharpens cognitive processes--primarily mathematics, organization, and memory--just as nicotine does. The results of a ten-year study, reported in the Archives of Internal Medicine, showed that female nurses between the ages of 34 and 59 who drank coffee were less likely to commit suicide than women who drank no coffee at all.

Until recently, coffee and tea were rarely thought of as drugs of abuse, even though it is certainly possible to drink too much caffeine. Are the xanthines, the family of compounds that includes caffeine, addictive?

The typical caffeine dose in a cup of coffee--between 50 and 200 milligrams, with an average of about 115 milligrams--is enough to produce a measurable metabolic effect. Supermarket coffee in a can has considerably more caffeine per brewed cup than gourmet blends. Robusta beans have more caffeine than Arabica varieties. Instant coffee is the most potent coffee of all. The side effects of overdose--excessive sweating, jittery feelings, and rapid speech--tend to be transient and benign. Withdrawal is another matter: Caffeine causes a surge in limbic dopamine and norepinephrine levels--but not solely at the nucleus accumbens. The prefrontal cortex gets involved as well.

Caffeine's psychoactive power and addictive potential are easily underestimated. The primary receptor site for caffeine is adenosine, which, like GABA, is an inhibitory neurotransmitter. Adenosine normally slows down neural firing. Caffeine blocks out adenosine at its receptors, and higher dopamine and norepinephrine levels are among the results. Taken as a whole, these neurotransmitter alterations result in the bracing lift, the coffee "buzz" that coffee drinkers experience as pleasurable.

Scientists at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) have demonstrated that high doses of caffeine result in the growth of additional adenosine receptors in the brains of rats. In order to feel normal, the rats must continue to have caffeine. Take away the caffeine, and the brain, now excessively sensitized to adenosine, becomes sluggish without the artificial stimulation of the newly grown adenosine receptors. Like alcoholics and cocaine addicts, people with an impressive tolerance for coffee and tea may find themselves chasing a caffeine high in a losing battle against fluctuating neuroreceptor growth patterns.

Increased tolerance and verifiable withdrawal symptoms, the primary determinants of addiction, are easily demonstrated in victims of caffeinism. Even casual coffee drinkers are susceptible to the familiar caffeine withdrawal headache, which is the result of caffeine's ability to restrict blood vessels and reduce the flow of blood to the head. When caffeine is withdrawn, the arteries in the head dilate, causing a headache. Caffeine's demonstrated talent for reducing headaches is one of the reasons pharmaceutical companies routinely include it in over-the-counter cold and flu remedies. The common habit of drinking coffee in the morning is not only a quick route to wakefulness, but also a means of avoiding the headaches associated with withdrawal from the caffeine of the day before.

--Adapted from The Chemical Carousel: What Science Tells Us About Beating Addiction © Dirk Hanson 2008, 2009.

Photo Credit: Lifehacker

[Note: For my Russian readers, a translation of this post is available here: "Зависимость от кофе translated by Health Effects of Coffee"]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)