Showing posts with label cannabis. Show all posts

Showing posts with label cannabis. Show all posts

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

Status of Medical Marijuana to be Tested in U.S. Appeals Court

Ten-year old petition could change everything.

Medical marijuana advocates will finally have their day in federal court, after the United States Court of Appeals for D.C. ended ten years of rebuffs by agreeing to hear oral arguments on the government’s classification of marijuana as a dangerous drug.

A decision in the case could either finish off medical marijuana for good, or else upend the fed’s rationale for its stepped-up war against the medical marijuana industry. Americans for Safe Access v. Drug Enforcement Administration asks that the federal government review the scientific evidence regarding marijuana’s therapeutic value. The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals has agreed to do so in October.

The original petition, filed by the Coalition for Rescheduling Cannabis (CRC) in 2002, has languished in obscurity, but recent moves to have marijuana rescheduled from its status as a Schedule 1 drug—a class that includes heroin—have increased in the wake of America’s Civil War over medical marijuana. “This is a rare opportunity for patients to confront politically motivated decision-making with scientific evidence of marijuana’s med efficacy,” said Joe Elford, chief council for Americans for Safe Access, the group that successfully challenged the denial of the original CRC petition. “What’s at stake in this case is nothing less than our country’s scientific integrity and the imminent needs of millions of patients.”

The Controlled Substance Act reserves Schedule 1 for drugs that “have a high potential for abuse, have no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and there is lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision.”

Recently, an article by Dr. Igor Grant in the Open Neurology Journal argued that marijuana’s Schedule 1 classification and surrounding political controversy were “obstacles to medical progress in this area.”

Seventeen states have now adopted some form of medical marijuana law, but the nascent field remains in limbo due to federal regulations about the illegality of marijuana use. Over the past year, the U.S. Justice Department has stepped up its pressure on medical marijuana purveyors, culminating in dozens of indictments, seizures, and shutdowns. Most recently, the Los Angeles City Council simply threw up its hands and banned most marijuana dispensaries in the city. But it’s not even clear if the ban on state-legal dispensaries is itself legal. A pot collective in Covina recently won its challenge to a blanket ban on pot sales in unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County in the state’s 2nd District Court of Appeal. As a Los Angeles Times editorial aptly put it, “we’re confused about how to legally restrict a quasi-legal business.”

According to Chris Roberts, writing in the SF Weekly, “the court hearing would be the first time the medical merits of cannabis would be examined in a federal courtroom since 1994.” At the core of the argument is the federal government’s contention that the marijuana plant has no redeeming medical value, as opposed to the mountain of scientific studies suggesting that marijuana may be applicable in the treatment of glaucoma, cancer, chronic pain, and possibly other conditions, such as multiple sclerosis.

Graphics Credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/

Wednesday, May 16, 2012

A Look at the Recent Study of Cannabis and Multiple Sclerosis

Smoked marijuana reduced spasticity in a small trial of MS patients.

The leading wedge of the medical marijuana movement has traditionally been centered on pot as medicine for the effects of chemotherapy, for the treatment of glaucoma, and for certain kinds of neuropathic pain. From there, the evidence for conditions treatable with marijuana quickly becomes either anecdotal or based on limited studies. But pharmacologists have always been intrigued by the notion of treating certain neurologic conditions with cannabis. Sativex, which is sprayed under the tongue as a cannabis mist, has been approved for use against multiple sclerosis, or MS, in Canada, the UK, and some European countries. (In the U.S., parent company GW Pharma is seeking FDA approval for the use of Sativex to treat cancer pain).

There is accumulating evidence that cannabinoid receptors may be involved in controlling spasticity, and that anandamide, the brain’s endogenous form of cannabis, is a specific antispasticity agent.

Additional evidence that researchers may be on to something appeared recently in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. Dr. Jody Corey-Bloom and coworkers at

Clearly, it’s hard for a study of this sort to be truly blind: Participants, one presumes, had little trouble distinguishing the medicine from the placebo. And in fact, an appendix to the study shows this to be true: “Seventeen participants correctly guessed their treatment phase for all six visits… For the remaining participants, cannabis was correctly guessed on 33/35 visits.” This raises the question of various kinds of self-selection bias and expectancy effects, and the study authors themselves write that the results “might not be generalizable to patients who are cannabis-naïve.” On the other hand, cannabis-naïve patients were in the minority. The average age of the participants was 50, and fully 80% of them admitted to previous “recreational experience” with cannabis. (I don’t have a good Baby Boomer joke for the occasion, but if I did, this is where it would go).

I asked Dr. Corey-Bloom about this potential problem in an email exchange: “The primary outcome measure was the Ashworth Spasticity Scale, which is an objective measure, carried out by an independent rater,” she wrote. “Their job was just to come in and feel the tone around each joint (elbow, hip, knee), rate it, and leave. That's why we think it was so important to have an objective measure, rather than just self-report.”

With all this in mind, the study found that “smoking cannabis reduced patient scores on the modified Ashworth scale by an average of 2.74 points.” The authors conclude: “We saw a beneficial effect of smoked cannabis on treatment-resistant spasticity and pain associated with multiple sclerosis among our participants.”

Other studies have found similar declines in spasticity from cannabinoids, but have tended not to use marijuana in smokable form.

Corey-Bloom, J., Wolfson, T., Gamst, A., Jin, S., Marcotte, T., Bentley, H., & Gouaux, B. (2012). Smoked cannabis for spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial Canadian Medical Association Journal DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.110837

Photo Credit: http://blog.amsvans.com/

Labels:

cannabis,

cannabis for MS,

marijuana,

medical marijuana

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

Marijuana: The New Generation

What’s in that “Spice” packet?

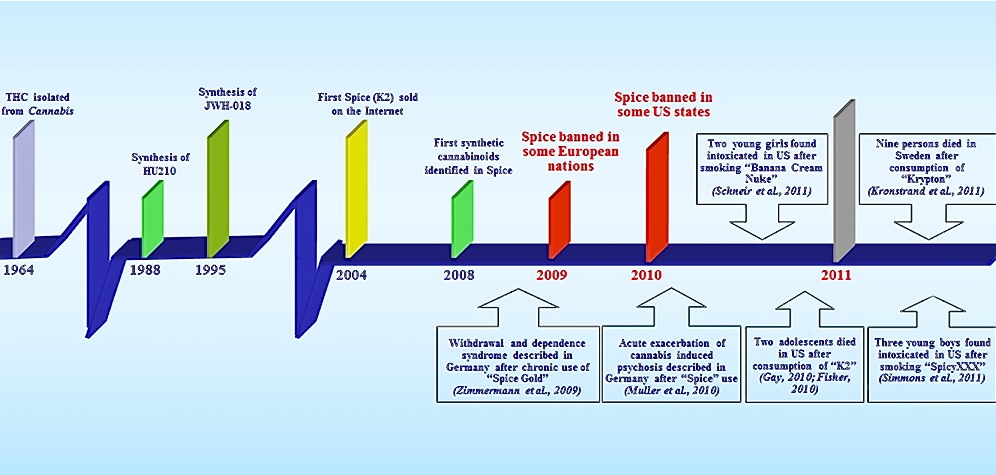

They first turned up in Europe and the U.K.; those neon-colored foil packets labeled “Spice,” sold in small stores and novelty shops, next to the 2 oz. power drinks and the caffeine pills. Unlike the stimulants known as mephedrone or M-Cat, or the several variations on the formula for MDMA—both of which have also been marketed as Spice and “bath salts”—the bulk of the new products in the Spice line were synthetic versions of cannabis.

The new forms of synthetic cannabis tickle the same brain receptors as THC does, and are sometimes capable of producing feelings of well-being, empathy, and euphoria—in other words, pretty much the same effects that draw people to pot. But along the way, users began turning up in the emergency room, something that very rarely happens in the case of smoked marijuana. The symptoms were similar to adverse effects some people experience with marijuana, but greatly exaggerated: extreme anxiety and paranoia, and heart palpitations.

As it turns out, there is a very real difference between smoking Purple Kush and snorting “Banana Cream Nuke” out of a metallic packet. The difference lies in the manner in which the brain’s receptors for cannabinoids are stimulated by the new cannabis compounds. When things goes wrong at the CB1 and CB2 receptors, and the mix isn’t right, the results may not be euphoria, giggles, short-term memory loss, and the munchies, but rather “nausea, anxiety, agitation/panic attacks,  tachycardia, paranoid ideation, and hallucinations.” Furthermore, the Spice variants do not contain cannabidiol, a cannabis ingredient that has been shown to reduce anxiety in animal models, and reduces THC-induced anxiety in human volunteers. The authors of a recent study suggest that the “lack of this cannabinoid in Spice drugs may exacerbate the detrimental effects of these herbal mixtures on emotion and sociability.”

tachycardia, paranoid ideation, and hallucinations.” Furthermore, the Spice variants do not contain cannabidiol, a cannabis ingredient that has been shown to reduce anxiety in animal models, and reduces THC-induced anxiety in human volunteers. The authors of a recent study suggest that the “lack of this cannabinoid in Spice drugs may exacerbate the detrimental effects of these herbal mixtures on emotion and sociability.”

What concerned the researchers was that, in addition to reports of cognitive deficits and emotional alterations and gastrointestinal effects, emergency room physicians were reporting wildly elevated heart rates, extremely high blood pressure, chest pains, and fever. Fattore and Fratta report that “two adolescents died in the USA after ingestion of a Spice product called ‘K2,’” one due to a coronary ischemic event, and the other due to suicide. What’s going on?

In a paper for Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience called “Beyond THC: the new generation of cannabinoid designer drugs,” Liana Fattore and Walter Fratta of the University Of Cagliari in Monserrato, Italy, identified more than 140 different products marketed as Spice, and laid out the extreme variability found in composition and potency. Like a mutating virus, they came to the U.S., starting in early 2009, a new strain seemingly every week: Spice, K2, Spice Gold, Silver, Arctic Spice, Genie, Dream, and dozens of others, the naming and renaming suggesting nothing so much as the proliferating strains of high-end marijuana: Skunk, Haze, Silver Haze, Amnesia, AK-47. Synthetic marijuana comes mainly from manufacturers in Asia, and second generation chemicals have already been put on a to-be-banned list by the DEA. States have jumped all over the problem with duplicate legislation, despite the fact that experts believe a majority of sales take place over the Internet. A third generation of synthetic cannabis variants, which are sprinkled on an herbal base and meant to be snorted, are openly sold and touted as legal. And they are legal, depending upon which one you buy, and where you buy it. Synthetic cannabis is still readily available, affordably packaged, and right on the shelf, or ready for purchase online—unlike the frequently vague and sometimes shady process of scoring a bag of weed. In the beginning, at least, the new drugs were perceived by youthful users as safer than other drugs.

But the most crucial attribute of Spice and related products is that they are not detectable in urine and blood samples. You can cruise all night on Spice, and test clean the next day at work. The kind of cannabis in Spice doesn’t read out on anybody’s drug tests as marijuana. That requires the presence of THC—and the new synthetics don’t have any.

There are four different categories of chemicals used in the manufacture of “cannabimimetic” drugs. The first and best known is the so-called JWH series of “novel cannabinoids” synthesized by John W. Huffman at Clemson University in the 1980s. The most widely used variant is an extremely potent version known as JWH-018. While JWH-018 is, chemically speaking, not structurally like THC at all, it snaps onto CB1 and CB2 receptors more fiercely than THC itself. The CP-compounds, the second class of synthetic compounds, were developed back in the 1970s by Pfizer, when that firm was actively engaged in testing cannabis-like compounds for commercial potential, a program they later dropped. The best-known example is CP-47,497. While CP-47,497 lacks the chemical structure of classic cannabinoids, it is anywhere from 3 to 28 times more potent than THC, and shows classic THC-like effects in animal studies. The next group is known as HU-compounds, because they originated at Hebrew University, where much of the early work on the mechanisms of THC took place. The last category consists of chemicals in the family of benzoylindoles, which also show an affinity for cannabinoid receptors.

JWH-018, the most common form of synthetic cannabis, and now widely illegal, is considerably more potent than THC—4 times stronger at the CB1 receptor, and 10 times stronger at the less familiar CB2 receptor. The CB2 receptor seems to have a lot to do with pain perception and inflammation, which is why researchers continue to investigate it. But CB2 receptors contribute only indirectly to the classic marijuana high, which is all about THC’s affinity for CB1 receptors, and the effects of using drugs with a very strong affinity for CB2 receptors is not well documented. And therein might lie the source of the problem—or, as Fattore and Fratta describe it, “the greater prevalence of adverse effects observed with JWH-018-containing products relative to marijuana.” A popular compound of the second kind, HU-210, has frequently been found in herbal mixtures available in the U.S. and U.K. According to the study, “the pharmacological effects of HU-210 in vivo are also exceptionally long lasting, and in animal models it has been shown to negatively affect learning and memory processes as well as sexual behavior.”

That, in a nutshell, is what the kids are smoking these days. But wait, there’s more: Besides synthetic cannabinoids, herbs and vitamins, researchers have found opioids like tramadol, opioid receptor-active compounds like Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa), and oleamide, a fatty acid derivative with psychoactive properties. (A combination of oleamide and JWH-018 has been sold as “Aroma.”) Indentifying which of these active ingredients is part of any particular packet of “legal highs” is further complicated by manufacturers’ tendency to mix the ingredients together with various organic compounds—everything from nicotine to masking agents like vitamin E. In fact, almost anything that might make it more difficult for forensic labs to pry it all apart: alfalfa, comfrey leaf, passionflower, horehound, etc. Banana Cream Nuke, which was purchased in an American smoke shop, and made two young girls very sick, contained 15 varieties of synthetic cannabis—but none of the herbal ingredients actually listed on the label.

Unlike the partial activation of CB1 receptors by THC, which takes place when people smoke marijuana, “synthetic cannabinoids identified so far in Spice products have been shown to act as full agonists with increased potency, thus leading to longer durations of action and an increased likelihood of adverse effects.” When it comes to cannabis, users are far better off smoking the real thing, from a harm reduction standpoint, and staying clear of these unpredictable synthetic substitutes.

Graphics Credit: http://www.cityblends.info/2011/10/beyond-thc.html

Fattore, L., & Fratta, W. (2011). Beyond THC: The New Generation of Cannabinoid Designer Drugs Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 5 DOI: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00060

Labels:

cannabis,

DEA bans spice,

designer drugs,

fake marijuana,

Huffman,

JWH-018,

k2,

marijuana,

synthetic marijuana,

THC

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Decoding Dope

Why marijuana gets you high, and hemp doesn’t.

Cannabis sativa comes in two distinct flavors—smokeable weed, and headache-inducing hemp. The difference between hemp and smokeable marijuana is simple: Hemp, used for fiber and seed, contains only a tiny amount of THC, the primary active ingredient in the kind of cannabis that gets you high. I am old enough to recall the sad saga of California hippies driving through my natal state of Iowa, and filling their trunks with “ditch weed”—wild hemp that grows commonly along Iowa rural fencerows, and while it cannot get you high, it could, back then, get you arrested.

But the California hippies who ran afoul of the law in Iowa were not so stupid as it might seem.

A study by a group of Canadian researchers, just published in Genome Biology, lays out the draft genome of marijuana, containing all of the plant’s hereditary information as encoded in DNA and RNA.In their article, Timothy Hughes, Jonathan Page and co-workers reported “a draft genome and transcriptome sequence of C. sativa Purple Kush.” (The genome and transcriptome can be browsed or downloaded at The Cannabis Genome Browser.) More than 20 plant genomes have now been sequenced, including corn and rice, but Cannabis sativa marks the first genomic sequencing of a traditional medicinal plant.

So how does it happen that one version of cannabis comes power packed, while the other version shoots blanks, so to speak? The researchers began with the modern facts of the matter: The THC content of medical and recreational marijuana is “remarkably high.” Research shows that median levels of THC in dried female flowers of Purple Kush (the strain used in the study) and other high-end variants now approach 11%, with some strains achieving a stratospheric 23% THC content by dry weight. Why can’t breeders pull any buzz out of ditch weed? How did cannabis split into two distinct subtypes? In an accompanying editorial entitled “how hemp got high,” Naomi Attar calls Cannabis sativa “a plant with a ‘split personality,' whose Dr. Jekyll, hemp, is an innocent source of textiles, but whose Mr. Hyde, marijuana, is chiefly used to alter the mind.” In brief, what are the biological reasons for the psychoactive differences between marijuana and hemp?

Co-lead author Jon Page, a plant biologist at the University of Saskatchewan, along with Tim Hughes of the Department of Molecular Genetics at the University of Toronto, compared the genomic information of Purple Kush, a medical marijuana favorite, with a Finnish strain of hemp called Finola, which was developed for oil seed production and contains less than 1% THC content. That is not enough THC to be mind-altering in any way. Instead, what Finola has in abundance is cannabidiol, or CBD, the other major ingredient in cannabis.

CBD isn’t considered psychoactive, but it does produce a host of pharmacological activity in the body. CBD shows less affinity for the two main types of cannabis receptors, CB1 and CB2, meaning that it attaches to receptors more weakly, and activates them less robustly, than THC. The euphoric effects of marijuana are generally attributed to THC content, not CBD content. In fact, there appears to be an inverse ratio at work. According to a paper in Neuropsychopharmacology, "Delta-9-THC and CBD can have opposite effects on regional brain function, which may underlie their different symptomatic and behavioral effects, and CBD's ability to block the psychotogenic effects of delta-9-THC."

The kind of cannabis people want to buy has a high THC/low CBD profile, while the hemp chemotype is just the reverse—low THC/high CBD. While the medical marijuana movement has concentrated on Purple Kush and other high-THC breeds, medical researchers have often tilted towards the CBD-heavy variants, since CBD seems to be directly involved with some of the purported medicinal effects of the plant. So, CBD specifically does not produce the usual marijuana high with accompanying euphoria and forgetfulness and munchies. What other researchers have discovered is that pot smokers who suffer the most memory impairment are the ones smoking cannabis low in cannabidiol, while people smoking cannabis high in cannabidiol—cheap, seedy, brown weed—show almost no memory impairment at all. THC content didn't seem to matter. It was the percentage of CBD that controlled the degree of memory impairment, the authors of earlier studies concluded.

The researchers found evidence in Purple Kush for “upregulation of cannabinoid ‘pathway genes’ and the exclusive presence of functional THCA synthase.” That means the reason hemp doesn’t get you high is because it is lacking the crucial enzyme—THCA synthase—that limits production of CBD and allows the production of THC to go wild. In contrast, cannabis strains producing high levels of THC—the Kushes and Hazes and White Widows and other seriously spendy variants—do have high levels of the enzyme that limits the production of CBD. Purple Kush gets you high because it has a built-in chemical brake on the production of CBD. Hemp doesn’t.

In a press release from the University of Saskatchewan, the researchers explain how they think this divergence came about: “Over thousands of years of cultivation, hemp farmers selectively bred Cannabis sativa into two distinct strains—one for fiber and seed, and one for medicine.” This intensive selective breeding resulted in changes in the essential enzyme for THC production, which “is turned on in marijuana, but switched of in hemp,” as Page put it. Furthermore, says co-leader Tim Hughes of the Department of Molecular Genetics at the University of Toronto, an additional enzyme responsible for removing materials required for THC production was “highly expressed in the hemp strain, but not the Purple Kush.” The loss of this enzyme in Purple Kush eliminated a substance “which would otherwise compete for the metabolites used as starting material” in THC production.

Without knowing the mechanics of it, underground growers and breeders have been steadily maximizing the cultivation of strains of cannabis high in THCA synthase, the result of which is a molecular blocking maneuver that maximizes THC production. This is great for getting high, but may not be the optimal breeding strategy for producing plants with medicinal properties. Raphael Mechoulam, the scientist who first isolated and synthesized THC, has referred to plant-derived cannabinoids as a “neglected pharmacological treasure trove.” The authors of this study agree, and have already identified some candidate genes that encode for a variety of cannabinoids with “interesting biological activities.” Such knowledge, they say, will “facilitate breeding of cannabis for medical and pharmaceutical applications.”

But cannabis of this kind may turn out to be low-THC weed. And that may be a good thing, some researchers believe. Marijuana expert Lester Grinspoon told Nature News: "Cannabis with high cannabidiol levels will make a more appealing option for anti-pain, anti-anxiety and anti-spasm treatments, because they can be delivered without causing disconcerting euphoria." (We’ll leave definitional issues about the effects of euphoria for another post.)

Finally, the authors strongly suggest that if it were not for “legal restrictions in most jurisdictions on growing cannabis, even for research purposes,” we would have known all of this stuff years ago, and would have been well on our way to developing “finer tailoring of cannabinoid content in new strains of marijuana,” as Nature News Blog describes it.

van Bakel H, Stout JM, Cote AG, Tallon CM, Sharpe AG, Hughes TR, & Page JE (2011). The draft genome and transcriptome of Cannabis sativa. Genome biology, 12 (10) PMID: 22014239

Photo Credit:http://www.medicinalgenomics.com/

Labels:

cannabis,

CBD,

genome,

hemp,

hemp production,

marijuana,

marijuana medicine,

medical marijuana,

skunk,

THC

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

Common Field Test for Marijuana is Unreliable, Critics Say

A 75-year old pot assay is due for an update.

We’ve all seen it on cop shows: The little plastic bag, the officer breaking the seal on a small pipette and inserting a bit of marijuana, then a firm shake, and voila, the liquid in the test satchel turns purple: Guilty.

Here’s an interesting twist they don’t tell you about: The so-called Duquenois-Levine test—the dominant method for field-testing marijuana since 1930—is considered by many to be wildly inaccurate, and frequently doesn’t hold up in court. One U.S. Superior Court judge referred to the test as “pseudo-scientific.”

The test itself works fine. The problem is that, in addition to identifying marijuana or hashish, the Duquenois-Levine, or D-L, frequently reads positive for tea, nutmeg, sage, and dozens of other chemicals—including resorcinols, a family of over-the-counter medicines, which, according to John Kelly at AlterNet, includes Sucrets throat lozenges. This does matter, because in New York, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere, inner-city minority kids are getting busted for pot in record numbers. Lacking a reliable test protocol, marijuana is whatever the officer says it is. In a classic case that continues to bedevil the testing industry, a middle-aged woman was busted for marijuana while bird watching. A “leafy substance” turned purple on the Duquenois-Levine (D-L) test, and the woman was arrested. The material turned out to be sage, sweetgrass, and lavender, and the woman was engaging in a Native American purifying ritual using a smudge, a concept with which the arresting officers were unfamiliar.

So, when push comes to shove, a positive D-L rarely establishes the presence of marijuana beyond a reasonable doubt, without further confirmatory testing. For at least 20 years now, a visual inspection and a NarcoPouch, as the D-L field test is called, were enough to bring on the felony charges. State courts have squabbled over the matter, but state legislatures have been reluctant to intervene, in large part because sending samples to a lab for confirmatory testing is prohibitively expensive, particularly when the busts are small. The D-L test saves money.

According to the official drug policy of the United Nations, a positive marijuana ID requires gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis. And even this far more sophisticated test has angered courts in Washington and Colorado, the UK Guardian reports, “because the DEA doesn’t have standard lab protocols to govern its use.” In part, the judges are furious because plea-bargaining depends upon valid drug possession evidence. So, the officers themselves, when it comes to testifying in court, become de facto expert witnesses, able to identify illegal drugs on sight. Ah, those were the days. But now, cannabis-based products come in a bewildering variety of sizes, shapes, colors, smells, and chemical compositions.

But c’mon, if it looks like bud and it smells like bud… except that the research shows there are 120 terpenoid-type compounds involved in the odor of marijuana. No two varieties smell exactly alike. There is no characteristic marijuana smell—there are hundreds of characteristic marijuana smells. Nonetheless, in 2009 the National Academy of Sciences called the testing of controlled substances “a mature forensic science discipline,” according to AlterNet.

In a 2008 article for the Texas Tech Law Review, Frederic Whitehurst, Executive Director for the Forensic Justice Project and formerly with the FBI, concluded: “We are arresting vast numbers of citizens for possession of a substance that we cannot identify by utilizing the forensic protocol that is presently in use in most crime labs in the United States.” In another section of the article, Whitehurst asks: “Why is this protocol still being utilized to decide whether human beings should be confined to cages and at times, to death chambers?” And as Stewart J. Lawrence and John Kelly write in the Guardian, “using manifestly flawed drug identification tests to charge defendants, or pressure them to plead guilty, is hard to square with a defendant’s right to due process.”

Photo Credit: http://www.howardcountydui.com/

Friday, July 15, 2011

There’s No Agreement on DUIC: Driving Under the Influence of Cannabis

The ACLU squares off against law enforcement over how to measure marijuana impairment.

What’s your blood cannabis content? You don’t know, and neither does anybody else, without a fair bit of effort. There’s no device to blow into, no quick chemical field test. You’re impaired by marijuana if the officer says you’re impaired by marijuana, and in most states he or she will decide that matter by using a series of sobriety checks not dissimilar to the well-known alcohol exercises: standing on one foot, walking a line, having your eyeballs and blood pressure checked—and my personal favorite, a test of how well you can guess when 30 seconds is up. Time passes more slowly when you’re about to be arrested for drugs, I’m guessing, since it takes a little while for your life to pass before your eyes. Even the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration admits that it is “difficult to establish a relationship between a person's THC blood or plasma concentration and performance impairing effects. Concentrations of parent drug and metabolite are very dependent on pattern of use as well as dose."

The point is, observable indications of impairment, as they’re called, are really all that law enforcement currently has as a tool for policing the use by drivers of American’s second most popular drug. At one extreme end of the spectrum are the pot enthusiasts who argue that no amount of marijuana significantly impairs you behind the wheel. At the other end of the spectrum stand the zero-tolerance advocates: No amount of marijuana is safe, if you’re planning to get behind the wheel within the next several hours—or at any time during the rest of your life, as some anti-drug advocates seem to be saying.

And somewhere in between, according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Washington State, lies a possible compromise for gauging marijuana impairment. “Adding a science-based threshold for likely impairment to the mix and providing educational information that allows people to estimate their personal level of intoxication can be effective strategies for preventing impaired driving in the first place and improving public safety,” the ACLU asserts.

The ACLU favors the so-called Pennsylvania Model, which sets that state’s legal limit for cannabis in whole blood at 5 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). Why 5, and not some other number? Because a legal cut-off of 5 ng/mL is also what the National Organizaton for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) recommends, based in turn on an analysis of scientific studies of marijuana’s effect on driving skills. Specifically, NORML recommends a limit in the range of 3.5-5.0 ng/mL, which the group says will “clearly separate unimpaired drivers with residual THC concentrations of 0-2 ng/mL from drivers who consumed cannabis within the last hour or so.” Levels under that range tend to indicate that the driver smoked at least 1 to 3 hours ago. Anyone testing over that range, says NORML is “likely to be impaired.”

But it’s not quite that simple, of course. First, you have to rule out a whole roster of cannabis metabolites that stay in the system for days or weeks, but have no impact on driving skills. And the metabolism of cannabinoid by-products varies so widely from person to person (this is just beginning to be understood scientifically), that the results of testing are not foolproof. The iron law of metabolic diversity makes that claim unlikely. Moreover, there is currently no reliable way of testing blood in the field for THC concentrations. But there will be. Introducing the Vantix Biosensor, a device that looks, ironically, like a portable vaporizer for marijuana. Open your mouth, please, as the officer politely swabs the inside of your cheek with a plastic wand, and inserts the wand in the handheld machine. Sensors on a microchip react with telltale antibodies, and you test positive for cocaine, or marijuana, or, soon, synthetic marijuana. Or perhaps it will be some other company’s device. But rest assured it is being looked upon as a growth market.

And then there is, as the ACLU points out, the wrong way to go about it: zero tolerance. At least 11 states have now set the requisite cut-off level for illegal drugs at zero. That may raise a cheer in certain quarters of the anti-drug movement, but it is a decision “based not in science but on convenience,” says the ACLU. It establishes a crime wholly “divorced from impairment” behind the wheel. Put simply, zero tolerance “does not differentiate between a dangerously incapacitated driver and an individual who may have smoked the past Monday but was pulled over as a sober ‘designated driver’ on Saturday night.” Furthermore, “even a statute excluding cannabis metabolites but criminalizing trace amounts of THC” could result in the arrest of drivers several days after they last smoked pot. It’s pretty simple, really. “If science dictates that the presence of a trace amount of cannabis or a cannabis metabolite in an individual’s blood has NO ‘influence’ on his capacity to drive, it should not constitute per se evidence of ‘driving under the influence.’” But toxicologist Marilyn Huestis, at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, disagrees. She believes that there is no safe level of marijuana consumption, where driving is concerned. Paul Armentano, deputy director for NORML, scoffs at that, telling the Los Angeles Times that individual states “are not setting a standard based on impairment, but one similar to saying that if you have one sip of alcohol you are too drunk to drive for the next week.”

One abiding problem is that for car accidents, it’s not necessarily a pure play. Alcohol mixed with one or more additional drugs is common, and if it’s difficult to set limits for alcohol and marijuana alone, imagine the permutations involved in creating legal limits for a combination of both. A 2007 survey of experimental studies, published in Addiction by a group of researchers in six countries, concluded that a rule of thumb police might want to consider is based on the finding that “a THC concentration in the serum of 7–10 ng/ml is correlated with an impairment comparable to that caused by a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.05%. Thus, a suitable numerical limit for THC in serum may fall in that range.” Considering that we allow drivers to exhibit blood alcohol limits as high as 0.08, NORML’s 5 ng/mL limit looks downright conservative.

There’s no simple solution. Maybe that’s because cannabis is not a simple drug. We’re still teasing apart its effects, and nailing down the particulars of driving under the influence of cannabis is one of them. As Jeffrey P. Michael of the National Highway Traffic Safety Adminstration refreshingly disclosed to the Los Angeles Times, “We don’t know what level of marijuana impairs a driver.” But they are trying to find out. A federal study in Virginia intends to round up more than 7,000 blood samples by showing up at the scene of car accidents and asking drivers to provide random, anonymous samples to compare with control samples.

Other studies of a similar nature are underway. Driving under the influence of drugs could become as common a criminal charge as classic DUIs and DWIs.

Photo credit: http://www.janisian.com/

Labels:

California pot laws,

cannabis,

driving under the influence,

DUI,

DUIC,

marijuana

Monday, December 6, 2010

Cannabis and Severe Vomiting

For those of you who missed this, as I did, here is a belated account of a rare but altogether curious side effect of heavy marijuana use: cyclical vomiting.

Nice, eh? And yes, it goes completely against the grain of what we think we know about marijuana: Ironically, cannabis is frequently employed to prevent the nausea and vomiting frequently associated with chemotherapy.

So what gives? The answer is that, so far, nobody really knows.

First things first: It appears to be a very rare side effect of regular marijuana use, and it was not documented in the medical literature until 2004. Given the long history of pot-smoking the world over, it is reasonable to ask where the cannabis emesis syndrome has been hiding all these years. A fair question, but one which, at this stage, has no satisfying answer.

Cannabinoid hyperemesis, as it's known, was first brought to wider attention earlier this year by the anonymous biomedical researcher who calls himself Drugmonkey. Posting on his eponymous blog, Drugmonkey documented cases of hyperemesis that had been reported in Australia and New Zealand, as well as Omaha and Boston in the U.S.

"There were two striking similarities across all these cases," Drugmonkey reported. "The first is that patients had discovered on their own that taking a hot bath or shower alleviated their symptoms. So afflicted individuals were taking multiple hot showers or baths per day to obtain symptom relief. The second similarity is, as you will have guessed, they were all cannabis users."

Heavy, regular cannabis users, most of them. And hot baths? Where did THAT come from?

More evidence was not long in coming. In February, researchers in the Division of Gastroenterology at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan, identified eight patients in their gastroenterology wards who were suffering from "otherwise unexplained refractory, recurrent vomiting." As the researchers reported in the journal Digestive Diseases and Sciences, there were two other significant features the eight patients shared: They were all chronic cannabis smokers--and they were all compulsive bathers.

The connection between uncontrolled vomiting and heavy toking seemed unequivocal: "Four out of five patients who discontinued cannabis use recovered from the syndrome," according to the published report, "while the other three patients who continued cannabis use, despite recommendations for cessation, continued to have this syndrome."

There is precious little anecdotal evidence to support this surprising finding. Occasionally, naive marijuana smokers will ingest too much and become sick to their stomach. And it is possible to incur the (brief) wrath of cyclic vomiting by eating way too many marijuana brownies, or other cannabis foodstuffs. Short of that, I am not familiar with vomiting as a documented side effect of regular cannabis use, and I venture to guess that most readers aren't, either.

However, the reports haven't stopped. This summer, an intriguing account appeared in Clinical Correlations, the official blog of New York University's Division of General Internal Medicine. Sarah A. Buckley and Nicholas M. Mark, 4th year medical students at the NYU School of Medicine, speculated on the cannabis hyperemesis phenomenon, and offered a formal definition: "A clinical syndrome characterized by intractable vomiting and abdominal pain associated with the unusual learned behavior of compulsive hot water bathing, occurring in the setting of long-term heavy marijuana use."

After reviewing 16 published papers on the syndrome, Buckley and Mark asked the obvious question: "How can marijuana, which is used in cancer clinics as an anti-emetic, cause intractable vomiting? And why would symptoms abate in response to high temperature?"

One possible mechanism involves marijuana's penchant for fats. Theoretically, this "lipophilicity" could cause increasingly toxic concentrations of THC over time, in susceptible people. "The abdominal pain and vomiting are explained by the effect of cannabinoids on CB-1 receptors in the intestinal nerve plexus," they write, "causing relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and inhibition of gastrointestinal motility." The authors speculate that low doses of THC might be anti-emetic, whereas in certain people, the high concentrations produced by long-term use could have the opposite effect.

As for the hot baths, Buckley and Mark note that "cannabis disrupts autonomic and thermoregulatory functions of the hippocampal-hypothalamic-pituitary system," which is loaded with CB-1 receptors. The researchers conclude, however, that the link between marijuana and thermoregulation "does not provide a causal relationship" for what they refer to as "this bizarre learned behavior."

These questions, like many questions having to do with regular marijuana use, are not likely to be answered definitively anytime soon, for a number of good reasons, some of which are delineated by the authors:

--"The legal status of marijuana makes eliciting an accurate drug history challenging."

--"The bizarre hot water bathing is likely often attributed to psychological conditions such as obsessive-compulsive behavior."

--"The knowledge of the anti-emetic effects of cannabis likely disguise cases of cannabinoid hyperemesis, leading to the erroneous belief that cannabis is treating cyclic vomiting rather than causing it."

--"The fact that this syndrome is so recently described and relatively unknown outside an esoteric subset of the GI [gastrointestinal] literature means that most clinicians are unaware of its existence."

Graphics Credit: http://www.oxygentimerelease.com/

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

Strong Pot: What Do Schizophrenics Think?

Small study asks patients for their opinions.

The theory, fiercely debated in the research community, that strong cannabis can actually cause schizophrenia—or is associated with relapse in schizophrenics who smoke it—is the subject of a small study from Switzerland on outpatient schizophrenics, some of whom were pot smokers.

A study of this kind, with only 10 subjects, verges on the anecdotal. Nonetheless, it is worth a look, just to see if any verification of the theory lurks therein.

In their paper for the open access Harm Reduction Journal—“Do patients think cannabis causes schizophrenia? A qualitative study on the causal beliefs of cannabis using patients with schizophrenia”—psychiatric workers with the Research Group on Substance Use Disorders interviewed patients who attended an outpatient clinic at the Psychiatric University Hospital in Zurich. The researchers did it because, as the paper states, “patients’ beliefs on the role of cannabis in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia have—to our knowledge—not been studied so far…”

“None of the patients described a causal link between the use of cannabis and their schizophrenia,” the researchers determined. However, several of the schizophrenics did have their own version of a disease model to account for their illness. Five of the patients attributed their schizophrenia to “upbringing under difficult circumstances,” and three placed the blame on “substances other than cannabis (e.g. hallucinogens).” The remaining two patients gave “other reasons.”

Interestingly, four of the patients “considered cannabis a therapeutic aid and reported that positive effects (reduction of anxiety and tension) prevailed over its possible disadvantages (exacerbation of positive symptoms).” The authors conclude that excluding schizophrenic patients from treatment settings because of marijuana use “may cause additional harm to this already heavily burdened patient group.”

Graphics Credit: http://www.salem-news.com

Sunday, October 3, 2010

Marijuana and Memory

Do certain strains make you more forgetful?

Cannabis snobs have been known to argue endlessly about the quality of the highs produced by their favorite varietals: Northern Lights, Hawaiian Haze, White Widow, etc. Among dedicated potheads, debates about the effects of specific cannabis strains are often overheated, and, ultimately, kind of boring. It's a bit like listening to a discussion of whether the wine in question evinces a woody aftertaste or is, instead, redolent of elderberries. For most people, the true essence of wine drinking is pretty straightforward: a drug buzz, produced by a 12 to 15 % concentration of ethyl alcohol derived from grapes, which can be had in a spectrum of varietal flavors.

However, there is no doubting that, unlike the case of wine, different strains of marijuana can have markedly different psychoactive effects. With weed, it's not just a matter of taste.

Over the past couple of years, the cannabis debate has taken a nasty turn, after British scientists published several controversial studies suggesting that high-THC "skunk" cannabis was responsible for increased mental problems among young people--including an increased risk of developing the symptoms of schizophrenia. British drug policy makers have continued to lead the charge on this, with mixed results. See my earlier post.

Recently, a study published in the British Journal Of Psychiatry concluded that marijuana

high in THC--including so-called "skunk" cannabis--caused markedly more memory impairment than varieties of marijuana containing less THC.

high in THC--including so-called "skunk" cannabis--caused markedly more memory impairment than varieties of marijuana containing less THC.

In an article at Nature News, Arran Frood spelled out the details of the study:

"Curran and her colleagues traveled to the homes of 134 volunteers, where the subjects got high on their own supply before completing a battery of psychological tests designed to measure anxiety, memory recall and other factors such as verbal fluency when both sober and stoned. The researchers then took a portion of the stash back to the laboratory to test how much THC and cannabidiol it contained.... Analysis showed that participants who had smoked cannabis low in cannabidiol were significantly worse at recalling text than they were when not intoxicated. Those who smoked cannabis high in cannabidiol showed no such impairment."

The two main ingredients in cannabis are THC and cannabidiol (CBD). CBD shows less affinity for the two main types of cannabis receptors, CB1 and CB2, meaning that it attaches to receptors more weakly, and activates them less robustly, than THC. The euphoric effects of marijuana are generally attributed to THC content, not CBD content. In fact, there appears to be an inverse ratio at work. According to a paper in Neuropsychopharmacology, "Delta-9-THC and CBD can have opposite effects on regional brain function, which may underlie their different symptomatic and behavioral effects, and CBD's ability to block the psychotogenic effects of delta-9-THC."

So, CBD specifically does not produce the usual marijuana high with accompanying euphoria and forgetfulness and munchies. What the researchers found was that pot smokers suffering memory impairment and those showing normal memory "did not differ in the THC content of the cannabis they smoked. Unlike the marked impairment in prose recall of individuals who smoked cannabis low in cannabidiol, participants smoking cannabis high in cannabidiol showed no memory impairment."

As far as memory goes, THC content didn't seem to matter. It was the percentage of CBD that controlled the degree of memory impairment, the authors concluded. "The antagonistic effects of cannabidiol at the CB1 receptor are probably responsible for its profile in smoked cannabis, attenuating the memory-impairing effects of THC. In terms of harm reduction, users should be made aware of the higher risk of memory impairment associated with smoking low-cannabidiol strains of cannabis like 'skunk' and encouraged to use strains containing higher levels of cannabidiol."

The idea that cannabidiol may protect against THC-induced memory loss is still quite speculative. Other research has suggested that a paucity of CB1 receptors may be protective against memory impairment. Marijuana growers select for high-THC strains, not high-CBD strains, and thus there is little data available about the CBD levels of most marijuana.

An earlier study in Behavioural Pharmacology by Aaron Ilan and others at the San Francisco Brain Research Institute did not find any connection between memory and CBD content. However, Ilan speculated in the Nature News article that the difference might have been due to methodology: In Britain, the subjects were studied using marijuana of their own choosing. In the U.S., National Institute of Health research policy has decreed that marijuana for official research must be supplied by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). And if there is one thing many researchers seem to agree on, it is that NIDA weed "is notorious for being low in THC and poor quality."

But CBD still does something, and that something just might be pain relief. Lester Grinspoon, a long-time marijuana researcher at Harvard Medical School, thinks that if the study proves out, it could have an important impact on the medical use of marijuana. Also quoted in Nature News, Grinspoon said: "Cannabis with high cannabidiol levels will make a more appealing option for anti-pain, anti-anxiety and anti-spasm treatments, because they can be delivered without causing disconcerting euphoria."

Morgan, C., Schafer, G., Freeman, T., & Curran, H. (2010). Impact of cannabidiol on the acute memory and psychotomimetic effects of smoked cannabis: naturalistic study The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197 (4), 285-290 DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077503

Graphics Credit: http://sites.google.com

Labels:

cannabis,

CB1,

CBD,

marijuana,

marijuana and memory,

memory impairment,

THC

Wednesday, August 1, 2007

Media Suffers Attack of Cannabis Psychosis

Bad Science Makes for Bad Science Journalism

According to the London Daily Mail, smoking a single joint of marijuana increases your risk of developing schizophrenia by 41 per cent. The Mail quoted Professor Robin Murray of the Institute of Psychiatry in London, who dutifully warned that the risk was perhaps even higher than that, due to the increasing use of what the newspaper termed “powerful skunk cannabis.” The skunk effect, said Murray, meant that the study’s estimate that “14 per cent of cases of schizophrenia in the UK are due to cannabis is now probably an understatement.”

Marjorie Wallace of the mental health charity SANE told BBC News: “The headlines are not scaremongering, but reflect a daily, and preventable, tragedy.”

Wow. As Gertrude Stein once put it, “Interesting if true.”

But it’s not true at all, of course. Or, to put it more accurately: If it were true, there is no way in hell the meta study under question could be used to prove it.

Speaking as a science journalist, this is the sort of thing than can really ruin your day.

As always, it helps to start with the original published article, a meta-analysis published in the British medical journal Lancet under the title, “Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review.” 2007 370: 319-28. Mark Hoofnagle, a MD/PhD Candidate in the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics at the University of Virginia, discussed the paper in depth on his Denialism Blog:

“First of all, the statement that ‘just one joint’ increases risk by 41% is absurd. The study here is of those who have tried marijuana once or more, not of people who have only tried it once. So already, the Daily Mail and every other news organization is way off. Second, I think we're ultimately seeing a post-hoc ergo propter hoc argument, and a dose-response that's more characteristic of the population studied than a real pharmacologic effect.”

Here’s why:

--People who suffer from a mental illness do more drugs than “normal” people. They are a high-risk population when it comes to addiction. There are people who have a propensity for addiction, and people who do not. Many of those who do will get hooked, but this does not mean that everything which follows is a result of the drugs.

--Latent schizophrenics often suffer their first break while under the influence of psychoactive drugs. Pot, along with LSD, physical trauma, the death of a loved one, and other intense emotional events can all trigger a schizophrenic break in late adolescence. So naturally there would be a correlation.

--The assumption that pot causes susceptibility to mental illness, rather than the other way around, can’t be proven. Hoofnagle uses the example of cigarette smoking. Anyone who has researched schizophrenia, or been around schizophrenics, knows that almost all schizophrenics smoke. (It helps quell hallucinations). Most of them began to smoke before the onset of their illness. Using the assumptions of the current study, we could say that cigarette smoking is almost certain to cause schizophrenia. Correlation, as Hoofnagle reminds us, is not causation.

--Daily pot smokers confound such a study. Are some of them exhibiting symptoms of schizophrenia, or are they exhibiting the symptoms of chronic marijuana intoxication? If they quit smoking so much, would they stop acting so crazy?

--Comorbidity is exceedingly common in drug addicts and users. There is a well-documented causal connection between depression and the use of psychoactive drugs. People suffering from depression often resort to cannabis and other drugs as a form of self-medication. Again, the mental condition leads to the drug use, and not the other way around.

--Finally, where is the epidemic of schizophrenia caused by millions of people smoking marijuana for years? What field evidence can be drawn upon to support this remarkable conclusion?

To be fair to the authors, bets are hedged. In their conclusion, Moore, et.al. state: “The possibility that this association results from confounding factors or bias cannot be ruled out, and these uncertainties are unlikely to be resolved in the near future.”

Nevertheless, the authors go on to conclude that “We believe that there is now enough evidence to inform people that using cannabis could increase their risk of developing a psychotic illness later in life.”

At www.badscience.net, Ben Goldacre wryly notes that “You know when cannabis hits the news you’re in for a bit of fun…” Of 175 studies identified as potentially relevant, Goldacre maintains that only 11 papers, describing 7 discrete data sets, actually turned to be relevant for purposes of the study. If every assumption in the paper is taken to be correct, and causality is accepted, Goldacre calculated, about 800 cases of schizophrenia per year could be attributed to marijuana in the U.K. “But what’s really important,” Goldacre writes, “is what you do with this data. Firstly you can misrepresent it….not least of all with the ridiculous ‘modern cannabis is 25 times stronger’ fabrication so beloved by the media and politicians.”

As it happens, all of this comes at a time in Britain when efforts to reclassify cannabis are being hotly debated in the government. As propaganda, the report is useful, but as a means of clarifying the debate, it will only produce confusion and demagoguery.

Sources:

--Moore, Theresa H.M., et. Al. “Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review.” Lancet. 2007 370: 319-28 http://www.thelancet.com/

--MacCrae, Fiona and Andrews, Emily. “Smoking just one cannabis joint raises danger of mental illness by 40%.” London Daily Mail. 26/07/07

--“Cannabis ‘raises psychosis risk.’” BBC News. 2007/07/27 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6917003.stm

--Cressey, Daniel. “Medical opinion comes full circle on cannabis dangers.” Nature. 27 July 2007.

--Hoofnagle, Mark. “Does Smoking Cannabis Cause Schizophrenia?” Denialism Blog. July 30, 2007. http://scienceblogs.com/denialism/2007/07/does_smoking_cannabis_cause_sc.php

Labels:

addiction,

cannabis,

marijuana,

psychosis,

schizophrenia,

withdrawal

Friday, July 27, 2007

Minister Says Marijuana is a Sacrament

That’s Reverend Stoner to you, brother

Nice try, Craig X. Rubin. But the California courts aren’t buying it. Ministers, mail-order or otherwise, are unlikely to merit federal protection for the use of pot as a church sacrament.

Ordained, as were so many of us, as a minister of the Universal Life Church, and thereby licensed to perform legal weddings and, in days gone by, to attempt conscientious objector status in military matters, Rubin was charged with possession with attempt to sell. The leader of the 420 Temple faces up to seven years in prison for dealing.

The 41 year-old Rubin has no legal experience but is representing himself in the case. Not much is known about his court strategy, but a two-pronged defense appeared to be emerging: Rubin will argue that marijuana is the “tree of life” mentioned in the Bible (if not in the movie, “The Fountain,”) and that an officer held a shotgun to his head during the arrest. He is not contesting the allegation of possessing pot, which he said the churches uses as a sacrament during services. He is currently free on $20,000 bail.

Rubin spent last weekend preparing for jury selection by consulting with Native American elders in as sweat lodge at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. This may not be as crazy as it sounds, as tribes in the West have accumulated considerable legal expertise in these matters due to the use of peyote in Native American Church rituals.

“He is as good as I’ve seen any defendant representing himself,” said Michael Levinsohn of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML).

In the event, Superior Court Judge Mary H. Strobel neatly side-stepped the federal issues at hand, ruling that the Reverent Rubin could not use federal statutes as a defense against state drug charges.

Sources:

--Glazer, Andrew. “Minister cites religious protection in marijuana defense.” Associated Press Newswire, 07/24/2007

--“Minister: Marijuana is a sacrament.” Focus on Faith, MSNBC.com. July 26, 2007. http://www.msnbc.msn.com

Sunday, May 13, 2007

Is Marijuana Addictive?

The argument continues.

The argument continues.For more, see Marijuana Withdrawal.

See also Marijuana Withdrawal Revisited

Marijuana may not be a life-threatening drug, but is it an addictive one?

There is little evidence in animal models for tolerance and withdrawal, the classic determinants of addiction. For at least four decades, million of Americans have used marijuana without clear evidence of a withdrawal syndrome. Most recreational marijuana users find that too much pot in one day makes them lethargic and uncomfortable. Self-proclaimed marijuana addicts, on the other hand, report that pot energizes them, calms them down when they are nervous, or otherwise allows them to function normally. They feel lethargic and uncomfortable without it. Heavy marijuana users claim that tolerance does build. And when they withdraw from use, they report strong cravings.

Marijuana is the odd drug out. To the early researchers, it did not look like it should be addictive. Nevertheless, for some people, it is. Recently, a group of Italian researchers succeeded in demonstrating that THC releases dopamine along the reward pathway, like all other drugs of abuse. Some of the mystery of cannabis had been resolved by the end of the 1990s, after researchers had demonstrated that marijuana definitely increased dopamine activity in the ventral tegmental area. Some of the effects of pot are produced the old-fashioned way after all--through alterations along the limbic reward pathway.

By the year 2000, more than 100,000 Americans a year were seeking treatment for marijuana dependency, by some estimates.

A report prepared for Australia’s National Task Force on Cannabis put the matter straightforwardly:

There is good experimental evidence that chronic heavy cannabis users can develop tolerance to its subjective and cardiovascular effects, and there is suggestive evidence that some users may experience a withdrawal syndrome on the abrupt cessation of cannabis use. There is clinical and epidemiological evidence that some heavy cannabis users experience problems in controlling their cannabis use, and continue to use the drug despite experiencing adverse personal consequences of use. There is limited evidence in favour of a cannabis dependence syndrome analogous to the alcohol dependence syndrome. If the estimates of the community prevalence of drug dependence provided by the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study are correct, then cannabis dependence is the most common form of dependence on illicit drugs.

While everyone was busy arguing over whether marijuana produced a classic withdrawal profile, a minority of users, commonly estimated at 10 per cent, found themselves unable to control their use of pot. Addiction to marijuana had been submerged in the welter of polyaddictions common to active addicts. The withdrawal rigors of, say, alcohol or heroin would drown out the subtler, more psychological manifestations of marijuana withdrawal.

What has emerged is a profile of marijuana withdrawal, where none existed before. The syndrome is marked by irritability, restlessness, generalized anxiety, hostility, depression, difficulty sleeping, excessive sweating, loose stools, loss of appetite, and a general “blah” feeling. Many patients complain of feeling like they have a low-grade flu, and they describe a psychological state of existential uncertainty—“inner unrest,” as one researcher calls it.

The most common marijuana withdrawal symptom is low-grade anxiety. Anxiety of this sort has a firm biochemical substrate, produced by withdrawal, craving, and detoxification from almost all drugs of abuse. It is not the kind of anxiety that can be deflected by forcibly thinking “happy thoughts,” or staying busy all the time. A peptide known as corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) is linked to this kind of anxiety.

Neurologists at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, noting that anxiety is the universal keynote symptom of drug and alcohol withdrawal, started looking at the release of CRF in the amygdala. After documenting elevated CRF levels in rat brains during alcohol, heroin, and cocaine withdrawal, the researchers injected synthetic THC into 50 rats once a day for two weeks. (For better or worse, this is how many of the animal models simulate heavy, long-term pot use in humans). Then they gave the rats a THC agonist that bound to the THC receptors without activating them. The result: The rats exhibited withdrawal symptoms such as compulsive grooming and teeth chattering—the kinds of stress behaviors rats engage in when they are kicking the habit. In the end, when the scientists measured CRF levels in the amygdalas of the animals, they found three times as much CRF, compared to animal control groups.

While subtler and more drawn out, the process of kicking marijuana can now be demonstrated as a neurochemical fact. It appears that marijuana increases dopamine and serotonin levels through the intermediary activation of opiate and GABA receptors. Drugs like naloxone, which block heroin, might have a role to play in marijuana detoxification.

In the end, what surprised many observers was simply that the idea of treatment for marijuana dependence seemed to appeal to such a large number of people. The Addiction Research Foundation in Toronto has reported that even brief interventions, in the form of support group sessions, can be useful for addicted pot smokers.

--Excerpted from The Chemical Carousel: What Science Tells Us About Beating Addiction © Dirk Hanson 2008, 2009.

Labels:

addiction,

addictive,

cannabis,

drug addiction,

drugs,

marijuana,

marijuana addiction,

pot

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)