Wednesday, July 31, 2013

From “The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee”

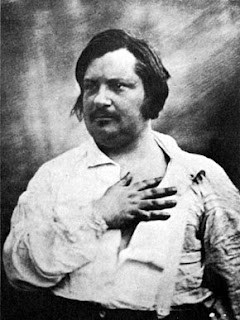

By Honore de Balzac, translated by Robert Onopa.

Coffee is a great power in my life; I have observed its effects on an epic scale….

Coffee affects the diaphragm and the plexus of the stomach, from which it reaches the brain by barely perceptible radiations that escape complete analysis; that aside, we may surmise that our primary nervous flux conducts an electricity emitted by coffee when we drink it. Coffee's power changes over time. [Italian composer Gioacchino] Rossini has personally experienced some of these effects as, of course, have I. "Coffee," Rossini told me, "is an affair of fifteen or twenty days; just the right amount of time, fortunately, to write an opera." This is true. But the length of time during which one can enjoy the benefits of coffee can be extended.

For a while - for a week or two at most - you can obtain the right amount of stimulation with one, then two cups of coffee brewed from beans that have been crushed with gradually increasing force and infused with hot water.

For another week, by decreasing the amount of water used, by pulverizing the coffee even more finely, and by infusing the grounds with cold water, you can continue to obtain the same cerebral power.

When you have produced the finest grind with the least water possible, you double the dose by drinking two cups at a time; particularly vigorous constitutions can tolerate three cups. In this manner one can continue working for several more days....

Finally, I have discovered a horrible, rather brutal method that I recommend only to men of excessive vigor... It is a question of using finely pulverized, dense coffee, cold and anhydrous, consumed on an empty stomach. This coffee falls into your stomach, a sack whose velvety interior is lined with tapestries of suckers and papillae. The coffee finds nothing else in the sack, and so it attacks these delicate and voluptuous linings; it acts like a food and demands digestive juices; it wrings and twists the stomach for these juices, appealing as a pythoness appeals to her god; it brutalizes these beautiful stomach linings as a wagon master abuses ponies; the plexus becomes inflamed; sparks shoot all the way up to the brain. From that moment on, everything becomes agitated. Ideas quick-march into motion like battalions of a grand army to its legendary fighting ground, and the battle rages. Memories charge in, bright flags on high; the cavalry of metaphor deploys with a magnificent gallop; the artillery of logic rushes up with clattering wagons and cartridges; on imagination's orders, sharpshooters sight and fire; forms and shapes and characters rear up; the paper is spread with ink - for the nightly labor begins and ends with torrents of this black water, as a battle opens and concludes with black powder.

I recommended this way of drinking coffee to a friend of mine, who absolutely wanted to finish a job promised for the next day: he thought he'd been poisoned and took to his bed, which he guarded like a married man. He was tall, blond, slender and had thinning hair; he apparently had a stomach of papier-mache. There has been, on my part, a failure of observation…."

Labels:

Balzac,

caffeine,

caffeine overdose,

coffee,

coffee addiction,

coffee overdose

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Crack Babies Are Turning Out Okay

Major study concludes that crack panic was overblown.

In an excellent story for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Susan FitzGerald traces the fortunes of Philadelphia children enrolled in a study that began in 1989, at the height of the crack “epidemic” in the U.S. Headed up by Hallam Hurt, then the chair of neonatology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, a group began the in-vitro study of babies exposed to maternal crack cocaine use. One of the longest-running studies of its kind, the NIDA-funded research on 224 babies born between 1989 and 1992, half of them cocaine-exposed, the other half normal controls, was now coming to a close. And the results were not what most people were expecting.

In the Inquirer article, Hurt notes that cocaine can in fact trigger premature labor, raise blood pressure, and risk a condition in which the placenta breaks loose from the uterine wall. So it was natural to go looking for long-term effects in all of those twitching, underweight newborn crack babies viewers saw on television. Physicians warned that damage to developing dopamine systems would result in long-term or permanent impairments in attention, language, and memory. So Hurt and colleagues went looking—and couldn’t find them. Neither could researchers at other institutions. Said Hurt: “We began to ask, ‘Was there something else going on?’”

As FitzGerald writes: “The years of tracking kids have led Hurt to a conclusion she didn’t see coming. ‘Poverty is a more powerful influence on the outcome of inner-city children than gestational exposure to cocaine,'" Hurt said. For example, babies born to mothers on heroin or methadone will have certain characteristic withdrawal symptoms, which can be managed by informed hospital staff. The same is true with newborns whose mothers have been using crack. In most cases, these withdrawals can be managed without permanent harm to the infant.

In a paper authored by Hurt, Laura M Betancourt, and others, the investigators write: “It is now well established that gestational cocaine exposure has not produced the profound deficits anticipated in the 1980s and 1990s, with children described variably as joyless, microcephalic, or unmanageable.” The authors do not rule out “subtle deficits,” but do not find evidence for them in functional outcomes like school or transition to adulthood.

How did this urban legend get started? In the 1980s, during the Reagan-Bush years, Americans were confronted with yet another drug “epidemic.” The resulting media fixation on crack provided a fascinating look at what has been called “drug education abuse.” This new drug war took off in earnest after Congress and the media discovered that an inexpensive, smokable form of cocaine was appearing in prodigious quantities in some of America’s larger cities. Crack was a refinement to freebasing, and a drug dealer’s dream. The “rush” from smoking crack was more potent, but even more transient, than the short-lived high from nasal ingestion.

Coupled with this development were the cocaine-related deaths of two well-known athletes, college basketball star Len Bias and defensive back Don Rogers of the Cleveland Browns. Bias played for Maryland, a home team in Washington, D.C. Six months earlier, Reagan had brought the military into the drug wars in a major way. The initial test of the directive was Operation Blast Furnace, a no-holds-barred attack on cocaine laboratories in the jungles of Bolivia.

As I wrote in 2008 in The Chemical Carousel:

The death of Len Bias elevated cocaine paranoia to the realm of the mythic. Cocaine became America’s first living-room drug, courtesy of the nightly news. The summer of 1986 will be remembered as the season of the “crack plague,” as viewers were bombarded with long news stories and specials. NBC Nightly News offered a special report on crack, during which a correspondent told viewers: “Crack has become America’s drug of choice... it’s flooding America....”

The hyperkinetic level of television coverage ultimately led TV Guide Magazine to commission a report from the News Study Group, headed by Edwin Diamond at New York University. The investigators quickly demolished the notion that cocaine had become America’s “drug of choice,” and were at a loss to account for where the networks had come up with it: “Statistically, alcohol and tobacco are the legal ‘drugs of choice’: 53 million people smoke cigarettes; 17.6 million are dependent on alcohol or abuse it. Marijuana still ranks as the No. 1 illegal drug. According to NIDA, 61.9 million people in the United States have experimented with marijuana.” The study group went on to note that the often-deadly “Black Tar” heroin had hit the streets of American cities the same summer. “Why was crack a big story [that summer] while Black Tar was not? One reason [is that] crack is depicted as moving into ‘our’—that is, the comfortable TV viewers’—neighborhood.”

Sunday, July 21, 2013

Fruit Fly Larvae Go Cold Turkey and Forget the Car Keys

Not a pretty sight.

Let’s start with the fruit fly, your basic Drosophila. A fruit fly, like a human, can become addicted to alcohol even at a very young age. The larval age. In other words, even as a maggot. And, just like humans, alcohol degrades a fruit fly maggot’s ability to learn. But adaption is an amazing thing, and drunken larvae eventually learn as well as their teetotaling cousins. That is, until the alcohol is taken away, in which case, the maggots become impaired learners once again. The larval nervous system goes haywire, and hyperexcitablity sets in. They can’t concentrate on their work. But one hour of “ethanol reinstatement” restores larval learning to normal levels.

It looks and sounds like withdrawal. Such effects in human alcoholics are often chalked up to state-dependent memory, but neurobiologists at the Waggoner Center for Alcohol and Addiction Research at the University of Texas, whose maggots these are, believe that state-dependent memory is not at work in the case of invertebrate ethanol dependence.

Brooks G. Robinson and associates fed the larvae a 5% ethanol supplement to their daily food. The maggots, incredibly enough, can reach blood-alcohol concentrations as high as 0.08, or roughly the legal limit for humans. If you blew a 0.08, the official chart says you would be suffering from impaired reasoning, disinhibition, and visual disturbances. For the maggots, no different. Larvae that fed on “ethanol food” for one hour learned poorly compared to straight maggots. The learning test, done before introducing alcohol into the picture, used a heat pulse to condition larvae away from an otherwise attractive odor. The reduced attraction to the odor is a form of associative learning. Figuratively speaking, the drunken maggots kept burning themselves on the stove as they reached for the soup. They failed the field sobriety test.

But was it truly a case of impaired learning? Perhaps the drunken larvae had an impaired sense of smell. But the researchers could not document a reduced sense of odor based on responses with untrained animals. And both groups of maggots sensed heat equally, so the reduction in learning was not due to simple alcoholic anesthesia. Could the withdrawal response be due to the fact that alcohol is a calorie-rich food? To test that possibility, the researchers ran the experiment with sucrose instead of alcohol, and didn’t record any learning impairment in that case. As for state-dependent memory, the researchers assert in Current Biology that withdrawal effects “cannot be attributed to state-dependent learning, because the less than 20 minute training and testing assay for all treatment groups occurs on nonethanol plates.”

And finally, the investigators write, “the fact that both the withdrawal-induced learning deficit and the neuronal hyperexcitability responses are reversed by ethanol reinstatement suggests that they have related origins, and that withdrawal learning may suffer because the nervous system is overly excitable.”

So what have we learned? Well, alcohol dependence in humans is clearly associated with learning and memory deficits that can last for a year or more after quitting. Now that the researchers have demonstrated cognitive alcohol dependence in invertebrates—for the first time ever, they say—it may open the door to more sophisticated genetic analyses of alcoholism in Drosophila, for all the reasons that have drawn other biologists to the study of fruit flies over the years.

And there is more research to be done relative to the finding that neuronal hyper-excitability is linked in some way to the learning deficits caused by alcohol. A brief article by Stefan Pulver in the Journal of Experimental Biology notes that the work of Robinson and colleagues “reinforces how eerily conserved ethanol’s physiological effects are across animal taxa. Alcohol addiction is truly the great leveller. It doesn’t matter whether you are man, mouse or maggot—over-consumption of alcohol will trigger very similar cellular and behavioral responses, with devastating consequences.”

Robinson B., Khurana S., Kuperman A. & Atkinson N. (2012). Neural Adaptation Leads to Cognitive Ethanol Dependence, Current Biology, 22 (24) 2338-2341. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.038

Sunday, July 14, 2013

MDPV Turns Lab Rats Into "Window Lickers"

Popular bath salt drug shown to be highly addictive.

Popular bath salt drug shown to be highly addictive. Researchers at the Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in La Jolla, California, appear to have hammered the last nail into the coffin for the common “bath salt” drug known as MDPV. We can now say with a high degree of certainty that, based on animal models, we know that 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone is addictive—perhaps more strongly addictive than methamphetamine, although such comparisons are always perilous. However, principal investigator Michael A. Taffe, an associate professor at TSRI, said in a prepared release that the research group “observed that rats will press a lever more often to get a single infusion of MPDV than they will for meth, across a fairly wide dose range.”

Like methamphetamine, MDPV works by stalling the uptake of dopamine, and it also has effects on noradrenaline and serotonin. As cathinone derivatives, MPDV and mephedrone are related to the stimulant drug khat, which is used like cocaine in northeastern Africa. In earlier research at Scripps under Dr. Taffe, investigators found that lab rats would intravenously self-administer mephedrone and behave in a manner similar to the effects produced when the rats were on methamphetamine. In a paper for Drug and Alcohol Dependence, the Taffe Lab concluded that “the potential for compulsive use of mephedrone in humans is likely quite high, particularly in comparison with MDMA.”

Now the researchers have zeroed in on the effects of the dirty pharmacology represented by MDPV, the other primary ingredient in many bath salt mixtures. In a new study by Michael Taffe, Tobin J. Dickerson, Shawn M. Aarde, and others, to be published in the August issue of Neuropharmacology, the investigators found that MDPV was a more potent attraction than meth for rats allowed to self-administer the drugs. Very little lab data exists for MDPV, and this study was among the first to directly compare the effect of MDPV to methamphetamine in an animal experiment.

It took some time to tease out the behavioral clues—the cognitive, thermoregulatory, and potentially addictive effects of the drug—but MDPV’s strong affinities with speed can no longer be ignored. The researchers saw the same types of repetitive activities seen in animals on meth, such as excessive grooming, tooth grinding, and skin picking. Lead author Shawn Aarde said in a prepared statement that “one stereotyped behavior that we often observed was a rat repeatedly licking the clear plastic walls of its operant chamber—a behavior that was sometimes uninterruptable.”

MDPV, in the jargon of such experiments, had “greater reward value” than methamphetamine. Which is saying something, given the well-publicized addictive threat of speed. When the group boosted the number of lever presses needed for another infusion of MDPV or meth, “we observed that rats emitted about 60 presses on average for a dose of meth but up to about 600 for MDPV—some rats would even emit 3,000 lever presses for a single hit of MDPV,” said Aarde in a press release. “If you consider these lever presses a measure of how much a rat will work to get a drug infusion, then these rats worked more than 10 times harder to get MDPV.”

Excuse me, did he say as many as three thousand bar presses for another bump of intravenous MDPV? He did. Overall, the rats self-administered more MDPV than methamphetamine. In the paper itself, the authors write that “compared with meth, the effect of MDPV on drug-reinforced behavior was of greater potency (more responding under lowest dose under fixed-ratio schedule) and greater efficacy (more responding under optimal dose under a progressive ratio schedule)…”

The conclusion? MDPV’s “abuse liability” may be greater than that of standard methamphetamine. Which is another excellent piece of evidence for approaching the world of new synthetic psychoactives with great caution.

Aarde S.M., Huang P.K., Creehan K.M., Dickerson T.J. & Taffe M.A. (2013). The novel recreational drug 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) is a potent psychomotor stimulant: Self-administration and locomotor activity in rats, Neuropharmacology, 71 130-140. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.003

Labels:

bath salt,

cathinone,

designer drugs,

MDPV,

mephedrone,

stimulants,

synthetic drugs

Saturday, July 6, 2013

Popular Synthetics: The Class of 2013

Navigating the new alphabet of intoxication.

You don’t have to be a molecular chemist to know which of today’s recreational drugs are safe. Wait, I take that back. You DO have to be a molecular chemist to navigate today’s synthetic drug market with anything like a modest degree of safety.

It’s hard not to get nostalgic: Back in the day, you had your pot, you had your acid, your coke, your speed, and your heroin. And that, with the exception of a few freak outriders like PCP, was about that. Baby boomers of today, already losing touch with leading-edge music—Macklemore? Tame Impala?—can now consider themselves officially out of touch when it comes to illegal drugs.

That is, unless they are familiar with psychoactive chemicals beyond mere methamphetamine “bath salt” knockoffs like mephedrone, and cannabis “Spice” look-alikes such as JWH-018. We’re talking about drugs like Bromo-DragonFly, Benzo Fury, and 2C-B. As Vanessa Grigoriadis writes in New York Magazine: “These drug users imagine themselves as amateur chemists, proto-Walter Whites, sampling and resynthesizing drugs to achieve exactly the state of consciousness they find most pleasurable. And there are no end of drugs to play with.”

A big piece of the synthetic drugs movement can be traced to the work of the legendary Alexander Shulgin, a Harvard grad who worked for Dow chemical, and who invented more than 100 entirely novel hallucinogenic compounds over the years. Other than the hallucinogens investigated by Shulgin and his coterie of personal friends, who were willing to take new hallucinogens and report back, none of the drugs on this list were meant for, or tested on, human beings.

Many of them are not, technically, new. Nonetheless, writes Grigoriadis, "almost every drug, from pot to GHB to morphine, has been messed with, as chemists find that removing a methoxy group or adding a benzene ring makes a new drug with different properties: body-grooving with a side helping of visuals, euphoric or speedy, long or short, or administering just the right dose of primal fear. Formerly known as “designer drugs,” they have morphed into “synthetic highs.” The tricky precursor chemical problem has become much easier to solve in the present moment, when any budding entrepreneur can send the official chemical designation of a drug, called its CAS number, to any of dozens of manufacturers in China, who will provide them with whatever weird “research” drug they need.

Herewith, a sampling of a few popular drugs of the day:

- 2C Series

- Bromo-Dragonfly

- NBOMe Series

- 6-APB (Benzo Fury)

- MDPV

- 5-MeO-DMT

Photo Credit: http://legalmann.wordpress.com/

Labels:

2C-B,

2C-P,

Benzo Fury,

Bromo-Dragonfly,

designer drugs,

DMT,

MDPV,

mephedrone,

Shulgin,

synthetic drugs

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)