Monday, June 2, 2014

Tripling the Tax on Alcohol

Would it do any good?

A recent article in Slate by Reihan Salam, a sort of modest proposal on behalf of a big boost in alcohol excise taxes, caught considerable flack from free market advocates and conservative bloggers last week.

Salam says Americans agree on the fact that marijuana is not as dangerous a drug as alcohol, and that this agreement offers us an opportunity to “regulate alcohol more stringently than we regulate marijuana.” In fact, Salam argues, why not push the envelope: “Raise the alcohol tax to a point just shy of where large numbers of people will start making moonshine in their bathtubs.”

Salam tries to head off some of the usual criticisms by noting that Prohibition was an unmitigated disaster, but that “what most of us forget is that the movement for Prohibition arose because alcohol abuse actually was destroying American society in the first decades of the 20th Century," and that companies like Anheuser Busch and MillerCoors are plotting with national retail chains as you read this, scheming to make alcohol as cheap and easy to buy as humanly possible.

Salam further justifies a tripling of alcohol taxes by viewing it as a tactical offset to the efforts of liquor companies to focus on their best customers: “the small minority of people who drink the most.” Salam says that right now, it costs about two bucks per inebriated hour to get your drink on. Can we really argue that this price level is just too unsustainably high? Drug expert Mark Kleiman, Professor of Public Policy at UCLA, agrees. In his book Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know, Kleiman and co-authors argue that “tripling the tax would raise the price of a drink by 20 percent and reduce the volume of drinking in about the same proportion. Most of the reduced drinking would come from heavy drinkers, both because they dominate the market in volume terms and because their consumption is more price-sensitive…."

Minnesota legislators recently passed a bill that opponents say would increase state excise taxes on alcoholic beverages to six times the current levels. Supporters of the alcohol tax say it means an extra $200 million per year to the state, at a cost to drinkers of about seven cents per drink. Or, in Salam's example: “Charging two-drink-per-day drinkers an extra $12 per month seems like a laughably small price to pay to deter binge drinking…. If you’re going to tax tanning beds and sugary soft drinks, why on earth wouldn’t you raise alcohol taxes too?”

Why wouldn’t you? Because it doesn’t accomplish what you want to accomplish, writes Michelle Minton at openmarket.org, the blog of the Competitive Enterprise Institute. After a bit of throat clearing about the Nanny State, Minton writes that “fortunately, a society’s relationship with alcohol isn’t based solely on the price of alcohol…. Research shows that alcohol price is not an effective means of achieving lower total consumption or reducing binge drinking.” As evidence, Minton points to studies showing that Luxembourg and the Czech Republic “have both the highest priced alcohol and the highest rates of consumption in Europe.”

As for a comparison favored by Salam—New York’s anti-smoking campaign—Minton admits that the new higher cost of cigarettes cut the adult smoking rate dramatically, but points out that “New York is now the number-one market for smuggled cigarettes—which account for more than half of all cigarettes smoked in the state.” This is a powerful argument. If we triple the taxes on alcohol, do we risk a black market of dangerous home-brew bootlegger booze?

In my view, such threats are real, but they are theoretical. The current costs of alcohol in socioeconomic terms are enormous and undeniable. Tripling the alcohol tax might be asking for trouble, but we could get there in stages if Americans saw it as a desirable goal. Arguments against tax increases tend to ignore the fact that alcohol is a different kind of product, capable of addicting a significant minority of users, in addition to killing a certain percentage of drinkers outright through alcohol poisoning and traffic accidents. If we ignore the issue of drug dependence, and the health and legal costs of assorted alcohol-related mayhem, and simply lean on the fact that most people who drink use alcohol responsibly, then it gets easier to argue against increases in alcohol and cigarette taxes. Alcohol is not like other household products, and needn't be regulated like them.

Labels:

alcohol,

alcohol tax,

alcoholism,

prohibition,

sin tax

Monday, May 26, 2014

Smoking Is Over If You Want It

Happy World No Tobacco Day

It’s one of the annual days of note concocted by the World Health Organization (WHO). The motive is undeniably noble, and the goofy negative title makes it a favorite of mine: Saturday, May 31, is the annual World No Tobacco Day.

This year, WHO and its partner organizations around the world are focusing on the economics of the global tobacco trade by urging nations to raise taxes on tobacco products. Raising taxes has two potential effects: It drives down consumption and it provides revenue for government health spending on tobacco-related illness and prevention. This latter concern will only grow in the U.S., as the aging boomer cohort reaches the decade of maximum ravagement from smoking-related diseases.

A tax increase that boosts the price of tobacco by 10% “decreases tobacco consumption by about 4% in high-income countries and by up to 8% in most low- and middle-income countries,” according to the organization. And this sweetener: “The World Health Report 2010 indicated that a 50% increase in tobacco excise taxes would generate a little more than US$ 1.4 billion in additional funds in 22 low-income countries. If allocated to health, government health spending in these countries could increase by up to 50%.”

What is the alternative? A bleak epidemic that will be killing more than 8 million people every year by 2030. “More than 80% of these preventable deaths will be among people living in low-and middle-income countries,” says WHO. The tax hammer is not as widely used for tobacco control as common sense might suggest. WHO says that “only 32 countries, less than 8% of the world's population, have tobacco tax rates greater than 75% of the retail price.” Even so, tobacco tax revenues are on average 175 times higher than spending on tobacco control, WHO data shows.

WHO also urges continued ad bans as a means of lowering consumption. “Only 24 countries, representing 10% of the world’s population, have completely banned all forms of tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. Around one country in three has minimal or no restrictions at all on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship.”

For more info, write the WHO Media Centre at mediainquiries@who.int.

Thursday, May 22, 2014

Single Bout of Binge Drinking Linked to Immune System Effects

The hazards of a leaky gut.

Biology for $1000, Alex: An integral part of the cell walls of Gram-negative bacteria, these toxic compounds can trigger inflammation and other immunological responses after a single episode of heavy drinking.

Answer: What are endotoxins?

The outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria contain toxic elements known as endotoxins, or lipopolysaccharides. An endotoxin is released when a bacterial cell wall is breached, allowing virulent proteins to enter the bloodstream. When endotoxins engage with the immune system, the result is inflammation—a necessary part of healing, yet potentially damaging to surrounding cells and tissue. When you come down with a cold, those aches and pains come are caused by your immune system inducing inflammation to fight the virus. Chronic inflammation is not a good thing. Higher levels of circulating endotoxins have been linked to numerous health issues.

Binge drinking: Almost everybody does it now and then, and some drinkers do it every day. So what is binge drinking, anyway? The NIAAA defines it as a drinking pattern that results in a blood alcohol level of 0.08 or above. This means about four drinks for women and five for men over a period of about two hours. “In chronic alcohol use activation of the inflammatory cascade is a major component of organ damage in the brain and liver,” according to researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. “Alcohol binge can cause altered immune functions that can also contribute to immunosuppression and reduced immune-mediated host defense to pathogens.”

Nobody ever claimed binge drinking was good for you. But the work done by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School on a small group of drinkers shows that a single episode of five drinks or more “can cause damaging effects such as bacterial leakage from the gut into the blood stream,” said Dr. George Koob, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study “tested the effects of acute binge drinking on serum endotoxin and bacterial 16S rDNA in normal human adults.” Led by Gyongyi Szabo, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, the study in PLOS ONE documented increases in endotoxin levels in the blood and evidence of bacterial DNA from the gut.

The investigators found that the concentration of endotoxin observed in the serum after an acute binge had significant biological activity, in particular a “significant induction of inflammatory cytokines.” In a prepared statement, Szabo said: “We found that a single alcohol binge can elicit an immune response, potentially impacting the health of an otherwise health individual. Our observations suggest than an alcohol binge is more dangerous than previously thought.” Fever, hypotension, and septic shock may develop due to endotoxins.

Compounding the harm to internal organs caused by alcohol is “gut permeability,” meaning that toxins have a better chance of escaping through the intestinal wall, wandering to other parts of the body, where they do harm. When you combine greater gut permeability with increased levels of circulating endotoxins, you get alcohol-related liver damage and other problems. Binge drinking, the researchers believe they have shown, is a good way to speed up that process.

In short, binge drinking helps gram-negative bacteria break the gastric barrier, escape the stomach, and colonize the small intestine, which puts them into systemic circulation. Bad news. The only bacteria that should be colonizing the small intestine is your neighborhood-friendly graham-positive Lactobaccilus, which aids digestion.

Unfortunately, the study also added to the growing mountain of evidence showing the ways in which alcohol affects women differently than men (See my report on gender-specific alcohol treatment in Scientific American.) Binge drinking showed a greater effect on women with respect to both endotoxemia and bacterial DNA levels.

According to the report: “Compared to men, women showed a slower decreased in blood alcohol levels (BAL), and even 24 hours after the alcohol binge BALs were higher in women than that in men…. Serum endotoxin levels were also higher in women after alcohol intake and a significant difference in endotoxin level was observed at 4 hours between men and women.”

Bala S., Marcos M., Gattu A., Catalano D. & Szabo G. (2014). Acute binge drinking increases serum endotoxin and bacterial DNA levels in healthy individuals., PloS one, PMID: 24828436

Thursday, May 8, 2014

Why the CDC Director Hates E-Cigarettes

The pros and cons of getting your vape on.

Last month, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began a new era—regulating e-cigarettes. With a non-controversial first step, the FDA banned the sale of e-cigarettes to minors, required health warnings, prohibited health claims, and outlined a plan to register and license all electronic nicotine products at some future date. The FDA’s proposed rules would also give the agency the power to regulate the currently unregulated mixture of chemicals and flavorings that are heated during e-cigarette use. Whatever regulations the FDA promulgates for electronic cigarettes will also apply to nicotine gels, water pipe tobacco, and hookahs.

Perhaps what rankles e-cigarette activists the most is the FDA’s insistence that companies will have to provide scientific evidence before making any implied claims about risk reduction for their product, compared with cigarettes. The FDA did not restrict advertising or prohibit flavorings (bubble gum, apple-blueberry, gummi bear, and cappuccino are popular).

Within a few days after the FDA’s announcement, Chicago, New York City, and other major cities placed e-cigarettes under the same municipal smoking bans as cigarettes.

The battle over e-cigarettes is both a public health issue and a private enterprise war for market share. Corporate giants Altria and Lorillard, which dominate the corporate tobacco landscape in the U.S., are fighting for a piece of what has become nearly a $2 billion market in a few short years. (Altria recently boosted its growth forecast to 6-9% growth for 2014). Lorillard has been making heavy acquisitions of its own, and commands more than half the present market with its Blu brand. Altria has made its own vapor acquisitions, and is launching its own brand, MarkTen.

So far, the moves being contemplated by the FDA do not have these companies shaking in their boots. They anticipated the ban on sales to minors, a system of formal FDA approval, a disclosure of ingredients, and health warnings about the addictive nature of nicotine. And Congress gave the FDA legal authority to draft a set of rules for e-cigarettes five years ago, so the FDA’s reluctance to step in on liquid nicotine delivery systems has been evident.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Tom Frieden, director of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), listed the reasons for his opposition to electronic cigarettes:

—E-cigarettes are an additional means of hooking another generation of kids on nicotine, making them more likely to become adult smokers.

—Smokers who might have quit smoking will maintain their nicotine addiction, remaining highly vulnerable to tobacco craving.

—Ex-smokers might make themselves more vulnerable to relapse if they take up vaping.

—Smokers might forego medications that could help them quit, in favor of the unproven promise of tobacco abstention via e-cigarette.

—E-cigarettes might have the cultural effect of “re-glamorizing” smoking.

—E-cigarette users might be exposing children and pregnant women to nicotine via secondhand smoke mechanisms.

—E-cigarette users can refill cartridges with liquid cannabis products and other drugs.

Dr. Michael Siegel, a tobacco expert at the Boston University School of Public Health, worries that smaller players will be squeezed out due to costs associated with the FDA approval process, driving sales toward the traditional cigarette industry leaders. Go-go analysts have predicted market penetration of as much as 50% for e-cigarettes, but Siegel is more pessimistic, and believes the e-cigarette share could top out at 10% if FDA regulations set back efforts by vaping proponents to position their product as a safer and healthier alternative to tobacco cigarettes. And that, says Siegel, would be a shame. He told the Boston Globe: “There simply is no product on the market that’s more dangerous than tobacco cigarettes, and nobody in their right mind would argue that cigarette smoking is less hazardous or even equally hazardous to vaping.”

Frieden at the CDC is sympathetic to the fact that many smokers have indeed quit smoking tobacco with the aid of e-cigarettes. “Stick to stick, they’re almost certainly less toxic than cigarettes.” But like many tobacco experts, he sees the possibility of a new generation of nicotine addicts. Almost two million high school kids have tried e-cigarettes, Frieden told the LA Times, “and a lot of them are using them regularly…. That’s like watching someone harm hundreds of thousands of children.” The CDC reported that the percentage of high school students who have used an e-cigarette jumped from 4.7% in 2011 to 10% in 2012. Calls to poison control centers involving children and e-cigarettes have increased sharply as well.

Frieden views the Food and Drug Administration as David under siege by Goliath. The FDA, he said, “tried to regulate e-cigarettes earlier, and they lost to the tobacco industry…. So the FDA has to balance moving quickly with moving in a way that’s going to be able to survive the tobacco industry’s highly paid legal challenge.” If E-cigarette makers really want to market to people trying to quit smoking, Frieden told the LA Times, “then do the clinical trials and apply to the FDA. But they don’t want to do that.” (See my post on Big Tobacco’s move into the e-cigarette market).

“It’s really the wild, wild West out there,” a beleaguered FDA commissioner Margaret Hamburg told the press. “They’re coming in different sizes, shapes and flavors in terms of the nicotine in them.”

On May 4, the New York Times published a report by Matt Richtel, based on an upcoming paper in the journal Nicotine and Tobacco Research. Nicotine researchers discovered that high-end electronic cigarette systems with refillable tanks produce formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, as a component of the exhaled nicotine vapor. Moreover, unlike disposable e-cigarettes, tank systems require users to refill them with liquid nicotine, itself a potent toxin. “Nicotine is a pesticide, fundamentally,” Michael Eriksen, dean of the School of Public Health at Georgia Statue University, told CNN. “We take so many precautions about pesticides for our lawns and how to wear gloves. But what precautions do consumers take when they put the nicotine vials in?”

This was not good news for harm reductionists, who view the advantages of e-cigarettes as self-evident. The New York Times report says that the toxin is formed “when liquid nicotine and other e-cigarette ingredients are subjected to high temperatures,” according to the research. “A second study that is being prepared for submission to the same journal points to similar findings.” In addition, a new study by researchers RTI International documents the release of tiny metal particles, including tin, chromium and nickel, which may worsen asthma and bronchitis.

Eric Moskowitz at the Boston Globe reported that “thousands of gas stations and convenience stores statewide carry e-cigarettes, usually stocking disposable or cartridge-based versions that resemble traditional cigarettes.”

In U.S. News, Gregory Conley, president of the trade group American Vaping Association, predicted “a huge influx of anti-e-cigarette legislation in the last half of 2014 and especially in 2015 when the legislative sessions get going again.”

According to Carl Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond, “it may be years before regulations are imposed. The lobbying at FDA and Congress will be intense.”

Effectively regulated, e-cigarettes have the potential to drastically reduce deaths from tobacco-related diseases among cigarette smokers. In an editorial for the journal Addiction, Sara Hitchman, Ann McNeill, and Leonie Brose of King’s College, London, wrote: “E-cigarettes may offer a way out of the smoking epidemic or a way of perpetuating it; robustly designed, implemented and accurately reported scientific evidence will be the best tool we have to help us predict and shape which of these realities transpires.”

Photo credit: http://ecigarettereviewed.com

Sunday, April 27, 2014

How Alcoholism Causes Muscle Weakness

It’s a mitochondrial thing.

Chronic alcohol intake weakens muscles. This condition can take the form of numbness or shooting pains in arms and legs, muscle cramps, fatigue, heat intolerance, and problems urinating. In some cases it can lead to diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, spasms, muscle atrophy, and movement disorders, even chronic pain and long-term disability. Leg symptoms are the most common. Alcohol-related neuropathy of this kind generally develops over time and gradually worsens. But until recently, the mechanism behind alcoholic neuropathy has remained obscure.

As it turns out, it’s a mitochondrial thing. Mitochondria, as we all remember from 10th grade biology, are little structures known as the “power plants” of cells. They are constantly changing tubular organelles that form networks inside of cells to convert oxygen into energy used in cellular processes. But if the proper enzymes that trigger the process go missing, less energy gets produced for activities like muscle function.

Patients with certain forms of mitochondrial disease, in which mitochondria fail to self-repair, show pronounced muscle weakness as a symptom. In some cases, this is due to a mutation for a particular mitochondrial fusion protein, leading to “late onset myopathy.”

Muscle tissue repairs itself through a process known as mitochondrial fusion, through which a broken mitochondrial cell component can repair itself by fusing with healthy mitochondria and exchanging bodily fluids, so to speak. It had previously been thought that the tightly packed fibers of muscle cells might not allow for normal fusion among the mitochondrial organelles found in skeletal muscle. Not so, according to a recent paper for the Journal of Cell Biology. Principle author Gyorgy Hajnoczky in the Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology at Philadelphia’s Thomas Jefferson University writes that the animal study shows how chronic alcohol exposure “suppresses mitochondrial fusion in muscle fibers.” The problem worsens over time due to “lesser metabolic fitness of the mitochondria, which progressively hinders calcium cycling during trains of stimulation.” What this means is that, in cases of prolonged heavy drinking, mitochondria have less “reserve capacity” for supporting calcium regulation in cells.

The researchers began with the known finding that “mitochondrial ultrastructure damage is apparent in the skeletal muscle of alcoholics, and mitochondria and their quality control are considered to be a primary target of chronic alcohol exposure.” Furthermore, “mitochondria represent a major target of alcohol and loose their normal shape upon persistent alcohol exposure.”

The study, funded by the NIAAA, demonstrated that mitochondrial fusion is the key to repair in skeletal muscle, as it is in other muscle tissue. In the study, researchers color-tagged mitochondria in the skeletal muscle of rats, and demonstrated that mitochondrial fusion occurs, and is governed by key players called mitofusin 1 fusion proteins (Mfn1). Chronic alcohol abuse interferes with this repair process. In the study, alcoholic rats showed a decrease in Mfn1 levels of up to 50 percent, while other fusion proteins were not affected.

“That alcohol can have a specific effect on this one gene involved in mitochondrial fusion suggests that other environmental factors may also alter specifically mitochondrial fusion and repair,” Hajnoczky said in a prepared statement.

The study has provided insight “into why chronic heavy drinking often saps muscle strength,” which could also “lead to new targets for medication development,” according to Dr. George Koob, head of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

Eisner V., Lenaers G. & Hajnoczky G. Mitochondrial fusion is frequent in skeletal muscle and supports excitation-contraction coupling, The Journal of Cell Biology, DOI: 10.1083/jcb.201312066

Photo Credit: http://mda.org

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

Marijuana Dependence and Legalization

Making best guesses about pot.

One essential question about state marijuana legalization continues to dog the debate: Namely, as marijuana becomes gradually legal, how do we estimate how many people will become dependent? How can we estimate the number of cannabis users who will become addicted under legalization, and who otherwise would not have succumbed?

Back in 2011, neuroscientist Michael Taffe of the Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, writing on the blog TL neuro, referenced this common question, noting that “the specific estimate of dependence rate will quite likely vary depending on what is used as the population of interest… Obviously, changing the size of the underlying population is going to change the estimated rate….”

But change it how, and by how much? The truth is, we don’t know. We can’t know in advance. There are sound arguments for both positions: Legal marijuana will lead to increased rates of cannabis addiction because of lower price and greater availability. On the other hand, almost everybody likely to become addicted to marijuana has probably already been exposed to it, including teens.

What we can start attempting to find out with greater rigor, however, is this: How many chronically addicted marijuana users are out there right now?

In The Pathophysiology of Addiction by George Koob, Denise Kandel, and Nora Volkow (2008), the base rate of cannabis dependence was estimated to be 10.3% for male users and 8.7% for female users. Their data came from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, and the rate is similar to common estimates for prescription stimulant addiction. The dependence rate for cigarettes is at least three times as high. However, an overall dependence rate of 9.7%, when men and women smokers are combined, is the origin of the highly contested figure of 10%.

Since then, other databases have been tapped for estimates of existing cannabis dependence. In October of 2013, using the Global Burden of Disease database maintained by the World Bank, British and Australian researchers, along with collaborators at the University of Washington in the U.S., published revised estimates in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, based on numbers from 2010. The scientists culled and pooled a series of epidemiological estimates and concluded that roughly 11 million cases of cannabis dependence existed worldwide in 1990, compared to 13 million cases in 2010. This boost can be accounted for in part by population increases.

Are these dependent users distributed evenly across the globe? They are not. The PLOS ONE paper demonstrates that marijuana use is markedly more prevalent in certain regions: “Levels of cannabis dependence were significantly higher in a number of high income countries including Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, and a number of Western European countries including the United Kingdom.” High income equals high marijuana usage and dependence—“Cannabis dependence in Australasia was about 8 times higher than prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa West.” But there may be major holes in the epidemiological database: “This is particularly the case for low income countries, where there is typically limited information on use occurring, even less on levels of use, and usually no data on prevalence of dependence.”

In conclusion, the researchers found an age and sex-standardized cannabis addiction prevalence of 0.2%. “Prevalence was not estimated to have changed significantly from 1990, although increased population size produced an increase in the number of cases of cannabis dependence over the period.”

In another 2008 study, this one published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, scientists at Columbia University and the New York State Psychiatric Institute looked at a set of 2,613 frequent cannabis users, using the development of significant withdrawal symptoms as the leading indicator. About 44% of regular dope smokers experienced two or more cannabis withdrawal symptoms, while about 35% reported three or more symptoms. The most prevalent symptoms in this study were fatigue, weakness, anxiety, and depressed mood. “Over two-thirds smoked more than 1 joint/day on days they smoked during their period of heaviest use; mean joints smoked/day was 3.9. About one-fifth had primary major depression….”

Age of onset was not predictive of withdrawal symptoms in this large study. The investigators suggest that “irritability and anxiety may receive great clinical consensus as regular features of cannabis withdrawal because they are subjectively and clinically striking compared to fatigue and related symptoms.” The researchers also speculate that somatic symptoms of weakness and fatigue might be attributed to varying levels of THC, compared to the presence of other cannabinoids such as CBD. The study is further evidence supporting an “association of primary panic disorder or major depression with cannabis depression/anxiety withdrawal symptoms,” suggesting a “possible common vulnerability, meriting further investigation.”

One of the reasons this matters is because of the very tight relationship between marijuana addiction and major depressive disorder. A 2008 study of young adults in the journal Addictive Behaviors found that participants with comorbid cannabis dependence and major depressive disorder, the most commonly dependence symptom was withdrawal, reported by more than 90% of the subjects in the study. 73% of the subjects experienced four symptoms or more. After that, the most common symptoms were irritability (an underreported but significant behavioral problem), restlessness, anxiety, and a variety of somatic symptoms, including gastrointestinal problems, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbances, including night sweats and vivid dreaming. The authors, affiliated with University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, concur with the conclusion of earlier researchers: “Given the weight of evidence now supporting the clinical significance of a cannabis withdrawal syndrome, the burden of proof must rest with those who would exclude the syndrome….”

Clearly, cannabis does not contribute to the world disease burden in the same way that alcohol, nicotine, and opiods do. However, it’s fair to say that for a minority of users, cannabis dependence causes disabilities and liabilities that are not always trivial.

Mark A. R. Kleiman, a Professor of Public Policy at UCLA and a consultant to the state of Washington on marijuana legalization, told PBS:

The couple of million who stay stoned all day, every day, account for the vast bulk of the total marijuana consumed, and thus the total revenues of the illicit marijuana industry. That's typical. The money in any drug, including alcohol, is in the addicts, not the casual users. There was a big fuss during the 80s about how much casual middle-class drug use there was and how respectable folks were supporting the markets. It's certainly true that most people who are illicit drug users are employed, stable respectable citizens. But it doesn't follow that if we could get the employed, stable respectable citizens to stop using illicit drugs, the problem would mostly go away.

Wednesday, April 9, 2014

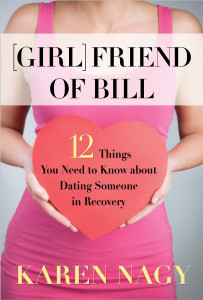

Tips For Dating a Person in 12 Step Recovery

Would you let your daughter go out with an addict?

In the title of her book, Girlfriend of Bill, author Karen Nagy riffs on the time-honored public code for mutual AA recognition: “Are you a friend of [AA co-founder] Bill?” Nagy says she was unable to find any material written “specifically for someone who is new to such a relationship or who is thinking about dating someone in recovery.” So she wrote one, and the publishing arm of Hazelden brought it out. People in Hazelden-style recovery (Nagy calls them “PIRs”) can present challenges, since, as Nagy learned by dating several of them, stopping drinking or using is not necessarily the end of the matter.

Readers should know that the book is written from the perspective of a member of Al-Anon, who is also a firm believer in the 12 Steps. But if dating people who participate in AA or NA is not your thing, than Nagy suggests dating people from SMART recovery, Secular Organizations for Sobriety, church, mental health peer support programs, therapy groups, and so on. Her own experience, however, appears mainly limited to men in and out of 12-Step recovery programs.

While the controversial disease model of addiction continues to provoke heated debate, Nagy discovered that “knowing addiction is a disease has helped me to confront and get over my past prejudices about alcoholics and drug addicts, and to better understand why they might think, act, and react the way they do.”

“Change is tough for all of us,” says Nagy, “but it can be especially hard for an addict” because of the strong tendency to rationalize and resist needed change. Addicts, she adds, “are also known for ‘wanting it now,’ a trait that could be related to their brain chemistry and addictive cravings.” (Or, as non-practicing addict Carrie Fisher memorably put it, “instant gratification takes too long.”)

Her summation of the notion behind the AA/NA concept of a higher power is a common one these days: “Some might call their Higher Power God; others might define it as nature, the positive energy of their group, or an unnamed sense of spirit.” While that may sound naïve to some, what the addict must grasp is that white-knuckle notions of triumph through personal will may have to be abandoned along the way, if we are talking about chronic, active addiction. And she correctly points out that the AA Big Book is “written in an old-fashioned style that hearkens back to the 1930s,” when the amateur self-help group known as AA was founded.

It’s easy to forget that there are common experiences that most recovering addicts are heir to. “We who care about a Person in Recovery are also powerless over alcohol and drugs,” Nagy writes. “Try as we might—we can’t control whether or not the PIR uses them.” And non-addicts who are dating them might usefully be forewarned about such things, Nagy believes. In addition, “It can take months for an addict’s body to adjust to abstinence,” she writes. “Aches and pains are common in withdrawal, and so are digestive problems that can include constipation, diarrhea, and loss of appetite… sleep disorders can be a huge problem….”

Nagy also tips boyfriends and girlfriends to the widening and primarily generational dispute over the use of medications for craving or associated mental health disorders. “Believing ‘a drug is a drug is a drug,’ many old-timers in recovery resist taking medications, whereas younger People in Recovery are more open to taking them if they need them.”

Addicts new to recovery may be coming off a period of social isolation, and a sense of being cut off from others. Nagy advises that a summary knowledge of the 12 Steps can be helpful, in particular the business about “making amends” to people one has harmed. Forgiveness is a touchy and ongoing bit of business. It never hurts to say you’re sorry, if in fact you are. Or to say it again.

Perhaps the single most common complaint takes the form of jealousy or irritation: Why is the Person in Recovery spending so much time with those other people, rather than with me? Aren’t I “supportive” enough? Nagy views the essence of AA/NA as a “spirituality of companionship—friends accompanying friends, helping, sharing, daring, celebrating, or grieving.” In the end, Nagy believes, “it’s not about religion; it’s about connection.”

In the title of her book, Girlfriend of Bill, author Karen Nagy riffs on the time-honored public code for mutual AA recognition: “Are you a friend of [AA co-founder] Bill?” Nagy says she was unable to find any material written “specifically for someone who is new to such a relationship or who is thinking about dating someone in recovery.” So she wrote one, and the publishing arm of Hazelden brought it out. People in Hazelden-style recovery (Nagy calls them “PIRs”) can present challenges, since, as Nagy learned by dating several of them, stopping drinking or using is not necessarily the end of the matter.

Readers should know that the book is written from the perspective of a member of Al-Anon, who is also a firm believer in the 12 Steps. But if dating people who participate in AA or NA is not your thing, than Nagy suggests dating people from SMART recovery, Secular Organizations for Sobriety, church, mental health peer support programs, therapy groups, and so on. Her own experience, however, appears mainly limited to men in and out of 12-Step recovery programs.

While the controversial disease model of addiction continues to provoke heated debate, Nagy discovered that “knowing addiction is a disease has helped me to confront and get over my past prejudices about alcoholics and drug addicts, and to better understand why they might think, act, and react the way they do.”

“Change is tough for all of us,” says Nagy, “but it can be especially hard for an addict” because of the strong tendency to rationalize and resist needed change. Addicts, she adds, “are also known for ‘wanting it now,’ a trait that could be related to their brain chemistry and addictive cravings.” (Or, as non-practicing addict Carrie Fisher memorably put it, “instant gratification takes too long.”)

Her summation of the notion behind the AA/NA concept of a higher power is a common one these days: “Some might call their Higher Power God; others might define it as nature, the positive energy of their group, or an unnamed sense of spirit.” While that may sound naïve to some, what the addict must grasp is that white-knuckle notions of triumph through personal will may have to be abandoned along the way, if we are talking about chronic, active addiction. And she correctly points out that the AA Big Book is “written in an old-fashioned style that hearkens back to the 1930s,” when the amateur self-help group known as AA was founded.

It’s easy to forget that there are common experiences that most recovering addicts are heir to. “We who care about a Person in Recovery are also powerless over alcohol and drugs,” Nagy writes. “Try as we might—we can’t control whether or not the PIR uses them.” And non-addicts who are dating them might usefully be forewarned about such things, Nagy believes. In addition, “It can take months for an addict’s body to adjust to abstinence,” she writes. “Aches and pains are common in withdrawal, and so are digestive problems that can include constipation, diarrhea, and loss of appetite… sleep disorders can be a huge problem….”

Nagy also tips boyfriends and girlfriends to the widening and primarily generational dispute over the use of medications for craving or associated mental health disorders. “Believing ‘a drug is a drug is a drug,’ many old-timers in recovery resist taking medications, whereas younger People in Recovery are more open to taking them if they need them.”

Addicts new to recovery may be coming off a period of social isolation, and a sense of being cut off from others. Nagy advises that a summary knowledge of the 12 Steps can be helpful, in particular the business about “making amends” to people one has harmed. Forgiveness is a touchy and ongoing bit of business. It never hurts to say you’re sorry, if in fact you are. Or to say it again.

Perhaps the single most common complaint takes the form of jealousy or irritation: Why is the Person in Recovery spending so much time with those other people, rather than with me? Aren’t I “supportive” enough? Nagy views the essence of AA/NA as a “spirituality of companionship—friends accompanying friends, helping, sharing, daring, celebrating, or grieving.” In the end, Nagy believes, “it’s not about religion; it’s about connection.”

Labels:

AA and higher power,

dating,

NA,

recovery

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)