Showing posts with label stop smoking. Show all posts

Showing posts with label stop smoking. Show all posts

Friday, February 27, 2015

The Blunt Facts About Blunts

Mixing tobacco with marijuana.

People who smoke a combination of tobacco and marijuana, a common practice overseas for years, and increasingly popular here in the form of “blunts,” may be reacting to some unidentified mechanism that links the two drugs. Researchers believe such smokers would be well advised to consider giving up both drugs at once, rather than one at a time, according to an upcoming study in the journal Addiction.

Clinical trials of adults with cannabis use disorders suggest that “approximately 50% are current tobacco smokers,” according to the report, which was published in the journal Addiction, and authored by Arpana Agrawal and Michael T. Lynskey of Washington University School of Medicine, with Alan J. Budney of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. “As many cannabis users smoke a mixture of cannabis and tobacco or chase cannabis use with tobacco, and as conditioned cues associated with smoking both substances may trigger use of either substance,” the researchers conclude, “a simultaneous cessation approach with cannabis and tobacco may be most beneficial.”

A blunt is simply a marijuana cigar, with the wrapping paper made of tobacco and the majority of loose tobacco removed and replaced with marijuana. In Europe, smokers commonly mix the two substances together and roll the combination into a single joint, the precise ratio of cannabis and nicotine varying with the desires of the user. “There is accumulating evidence that some mechanisms linking cannabis and tobacco use are distinct from those contributing to co-occurring use of drugs in general,” the investigators say. Or, as psychiatry postdoc Erica Peters of Yale put it in a press release, “There’s something about tobacco use that seems to worsen marijuana use in some way.” The researchers believe that this “something” involved may be a genetic predisposition. In addition to an overall genetic proclivity for addiction, do dual smokers inherit a specific propensity for smoked substances? We don’t know—but evidence is weak and contradictory so far.

Wouldn’t it be easier to quit just one drug, using the other as a crutch? The researchers don’t think so, and here’s why: In the few studies available, for every dually addicted participant who reported greater aggression, anger, and irritability with simultaneous cessation, “comparable numbers of participants rated withdrawal associated with dual abstinence as less severe than withdrawal from either drug alone.” So, for dual abusers, some of them may have better luck if they quit marijuana and cigarettes at the same time. The authors suggest that “absence of smoking cues when abstaining from both substances may reduce withdrawal severity in some individuals.” In other words, revisiting the route of administration, a.k.a. smoking, may trigger cravings for the drug you’re trying to quit. This form of “respiratory adaption” may work in other ways. For instance, the authors note that, “in addition to flavorants, cigarettes typically contain compounds (e.g. salicylates) that have anti-inflammatory and anesthetic effects which may facilitate cannabis inhalation.”

Studies of teens diagnosed with cannabis use disorder have shown that continued tobacco used is associated with a poor cannabis abstention rate. But there are fewer studies suggesting the reverse—that cigarette smokers fair poorly in quitting if they persist in cannabis use. No one really knows, and dual users will have to find out for themselves which categories seems to best suit them when it comes time to deal with quitting.

We will pass up the opportunity to examine the genetic research in detail. Suffice to say that while marijuana addiction probably has a genetic component like other addictions, genetic studies have not identified any gene variants as strong candidates thus far. The case is stronger for cigarettes, but to date no genetic mechanisms have been uncovered that definitively show a neurobiological pathway that directly connects the two addictions.

There are all sorts of environmental factors too, of course. Peer influences are often cited, but those influences often seem tautological: Drug-using teens are members of the drug-using teens group. Tobacco users report earlier opportunities to use cannabis, which might have an effect, if anybody knew how and why it happens.

Further complicating matters is the fact that withdrawal from nicotine and withdrawal from marijuana share a number of similarities. The researchers state that “similar withdrawal syndromes, with many symptoms in common, may have important treatment implications.” As the authors sum it up, cannabis withdrawal consists of “anger, aggression or irritability, nervousness or anxiety, sleep difficulties, decreased appetite or weight loss, psychomotor agitation or restlessness, depressed mood, and less commonly, physical symptoms such as stomach pain and shakes/tremors.” Others complain of night sweats and temperature sensitivity.

And the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal? In essence, the same. The difference, say the authors, is that cannabis withdrawal tends to produce more irritability and decreased appetite, while tobacco withdrawal brings on an appetite increase and more immediate, sustained craving. Otherwise, the similarities far outnumber the differences.

None of this, however, has been reflected in the structure of treatment programs: “Emerging evidence suggests that dual abstinence may predict better cessation outcomes, yet empirically researched treatments tailored for co-occurring use are lacking.”

The truth is, we don’t really know for certain why many smokers prefer to consume tobacco and marijuana in combination. But we do know several reasons why it’s not a good idea. Many of the health-related harms are similar, and presumably cumulative: chronic bronchitis, wheezing, morning sputum, coughing—smokers know the drill. Another study cited by the authors found that dual smokers reported smoking as many cigarettes as those who only smoked tobacco. All of this can lead to “considerable elevation in odds of respiratory distress indicators and reduced lung functioning in those who used both.” However, there is no strong link at present between marijuana smoking and lung cancer.

Some researchers believe that receptor cross-talk allows cannabis to modify receptors for nicotine, or vice versa. Genes involved in drug metabolism might somehow predispose a subset of addicts to prefer smoking. But at present, there are no solid genetic or environmental influences consistent enough to account for a specific linkage between marijuana addiction and nicotine addiction, or a specific genetic proclivity for smoking as a means of drug administration.

Agrawal, A., Budney, A., & Lynskey, M. (2012). The Co-occurring Use and Misuse of Cannabis and Tobacco: A Review. Addiction DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x

Photo credit: http://www.hightimes.com/

(First published at Addiction Inbox on March 22, 2012).

Labels:

blunts,

cigarettes,

marijuana,

marijuana addiction,

stop smoking

Wednesday, January 7, 2015

Rotting from the Inside

Smoking and the decline of the body.

We all know smoking is bad for your health. It causes lung cancer and emphysema and contributes to heart disease. But that’s not the end of the list. Recently, Public Health England, a government organization, collected and analyzed research on the contribution smoking makes to other forms of internal body damage. Authored by Dr. Rachael Murray of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies and the University of Nottingham, the study looked at the correlation between smoking and the musculoskeletal system, the cognitive system, dental health, and vision.

And the results of various meta-analyses are exactly as grim as we might expect. (You can download the PDF HERE.)

Bones, Muscle, and Tissue

Smoking does steady harm to the musculoskeletal system of habitual smokers. Osteoporosis in mature smokers may result from a loss of bone mineral density, a condition for which smoking “is a long established contributing risk factor.” There are a number of ways smoking can affect bone mineral density, says the report, including “decreased calcium absorption, lower levels of vitamin D, changes in hormone levels, reduced body mass, increased free radicals and oxidative stress, higher likelihood of peripheral vascular disease and direct effects of toxic components of tobacco smoke on bone cells.”

Moreover, smoking and broken bones go together like apple pie and ice cream, or in this case, bangers and mash. Overall in the UK, “current smokers have been reported to be at a 25% increased risk of any fracture,” the report concludes. The author notes that the greatest risk for smokers are seen at the hip and the lumbar spine, and women smokers in particular “were at a 17% greater risk of hip fracture at age 60, 41% at 70, 71% at 80 and 108% at 90.” The risk of fracture and the increased bone repair time decreases slowly in former smokers, and it may take 5 to 10 years before abstinent smokers see any statistical benefits.

Researchers have also documented a causal relationship between cigarette smoking and the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. But it is not known whether smoking cessation benefits existing patients with this condition.

As for soft tissue damage, a meta-analysis of 40 studies showed that smoking was associated with “a 33% increased prevalence of low back pain within the previous 12 months, 79% increased prevalence of chronic back pain and 114% increased prevalence of disabling lower back pain” among British smokers. Another study of 13,000 subjects showed that current and ex-smokers experienced up to 60% more pain in the lower back, upper neck and lower limbs than people who had never smoked. Smokers were also “74% more likely than non-smokers to have a rotator cuff tear,” Dr. Murray writes.

The Brain in Your Head

Chronic cigarette smoking hastens the decline in cognitive function that occurs with age. And there is a disturbing link between tobacco smoking and dementia: “A meta-analysis of eight studies published in 2008 reported that current smokers were 59% more likely than never-smokers to suffer Alzheimer’s disease and 35% more likely to suffer vascular dementia.” Earlier studies showed even higher risk percentages. Here, there is the possibility that smoking succession could reduce dementia onset. Two meta-analyses included in the report showed no association between former smoking and risk of dementia.

General cognitive impairment in adults over 50 is “consistently associated” with smoking, according to the UK report. “Faster declines in verbal memory and lower visual search speeds have been reported in male and female smokers aged 43 and 53, with the effect largest in those who smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day, independent of other potentially confounding factors.”

Dental Damage

Smoking is the primary cause of oral cancer, and the risk of developing it is three times less for non-smokers. Smoked and smokeless tobacco are linked to various non-malignant maladies of the soft and hard tissues in the oral cavity. Alcohol is a risk factor for oral cancer as well, “and is almost tripled in alcohol drinkers who smoke.”

Peridontitis, the inflammatory condition marked by bleeding gums and degeneration leading to tooth loss (and an associated greater risk of coronary heart disease) is three to four times as common in adult smokers. And although there are other confounding socioeconomic influences, smoking is also a risk indicator for missing teeth in older smokers and previous smokers. The increased peridontitis risk lasts for several years after smoking cessation.

As for cavities and general tooth decay (caries), “Although the association between smoking and prevalence of dental caries can be attributed to poor dental care and oral hygiene, a cross-section study with a four-year follow-up found that daily smoking independently predicts caries development in smokers.”

A Dim View

Neovascular and atrophic age-related macular degeneration, the eye conditions that cause a gradual loss of vision, are causally related to cigarette smoking. "A recent meta-analysis reported significant increases in macular degeneration of between 78% and 358%, depending on the study design." Smokers tend to develop the disease ten years earlier than non-smokers, and heavy smokers are at particular risk.

Finally, a number of cohort and case-control studies show a statistically significant link between smoking and cataracts, the cloudy patches over the eye that cause blurred vision. In current smokers, the increased risk is pegged at about 50%. "Smoking cessation reduces risks over time, however, the larger the exposure the longer it takes for the risk to reduce and this risk is unlikely to return to that of a never smoker."

Neovascular and atrophic age-related macular degeneration, the eye conditions that cause a gradual loss of vision, are causally related to cigarette smoking. "A recent meta-analysis reported significant increases in macular degeneration of between 78% and 358%, depending on the study design." Smokers tend to develop the disease ten years earlier than non-smokers, and heavy smokers are at particular risk.

Finally, a number of cohort and case-control studies show a statistically significant link between smoking and cataracts, the cloudy patches over the eye that cause blurred vision. In current smokers, the increased risk is pegged at about 50%. "Smoking cessation reduces risks over time, however, the larger the exposure the longer it takes for the risk to reduce and this risk is unlikely to return to that of a never smoker."

Photo credit: hhttp://www.healthcareaboveall.com/

Wednesday, December 3, 2014

Cigarettes and Genetic Risk

Evidence From a 4-Decade Study.

Pediatricians have often remarked upon it: Give one adolescent his first cigarette, and he will cough and choke and swear never to try another one. Give a cigarette to a different young person, and she is off to the races, becoming a heavily dependent smoker, often for the rest of her life. We have strong evidence that this difference in reaction to nicotine is, at least in part, a genetic phenomenon.

But so what? Is there any practical use to which such knowledge can be put? As it turns out, the answer may be yes. People with the appropriate gene variations on chromosomes 15 and 19 move very quickly from the first cigarette to heavy use of 20 or more cigarettes per day, and have more difficulty quitting, according to a report published last year in JAMA Psychiatry. From a public health point of view, these findings add a strong genetic rationale to early smoking prevention efforts— especially programs that attempt to “disrupt the developmental progression of smoking behavior” by means of higher prices and aggressive enforcement of age restrictions on smoking.

What the researchers found were small but identifiable differences that separated people with these genetic variations from other smokers. The gene clusters in question “provide information about smoking risks that cannot be ascertained from a family history, including information about risk for cessation failure,” according to authors Daniel W. Belsky, Avshalom Caspi, and colleagues at the University of North Carolina and Duke University.

The group looked at three prominent genome-wide association studies of adult smoking to see if the results could be applied to “the developmental progression of smoking behavior.” They used the data from the genome work to analyze the results of a 38-year prospective study of 1,037 New Zealanders, known as the Dunedin Study. A total of 405 cohort members in this study ended up as daily smokers, and only 20% of the daily smokers ever achieved cessation, defined as a year or more of continual abstinence.

The researchers came up with a multilocus genetic risk score (GRS) based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with smoking behaviors. Previous meta-analyses had identified several suspects, specifically a region of chromosome 15 containing the CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 gene cluster, and a region of chromosome 19 containing the gene CYP2A6. These two clusters were already strong candidate genes for the development of smoking behaviors. For purpose of the study, the GRS was calculated by adding up the alleles associated with higher smoking quantity. The genetic risk score did not pertain to smoking initiation, but rather to the number of cigarette smoked per day.

When the researchers applied these genetic findings to the Dunedin population cohort, representing ages 11 to 38, they found that an unfortunate combination of gene types seemed to be pushing some smokers toward heavy smoking at an early age. Individuals with a high GRS score “progressed more rapidly to heavy smoking and nicotine dependence, were more likely to become persistent heavy smokers and persistently nicotine dependent, and had more difficulty quitting,” according to the study. However, these effects took hold only when young smokers “progressed rapidly from smoking initiation to heavy smoking during adolescence.” The variations found on chromosomes 15 and 19 influence adult smoking “through a pathway mediated by adolescent progression from smoking initiation to heavy smoking.”

Curiously, the group of people who had the lowest Genetic Risk Scores were not people who had never smoked, but rather people who smoked casually and occasionally—the legendary “chippers,” who can take or leave cigarettes, sometimes have one late at night, or a couple at parties, without ever falling victim to nicotine addiction. These “light but persistent smokers” were accounted for “with the theory that the genetic risks captured in our score influence response to nicotine, not the propensity to initiate smoking.”

Naturally, the study has limitations. Everyone in the Dunedin Study was of European descent, and the life histories ended at age 38. Nor did the study take smoking bans or different ages into account. The study cries out for replication, and hopefully that won’t be long in coming.

Could information of this sort be used to identify high-risk young people for targeted prevention programs? That is the implied promise of such research, but no, probably not. The gene associations are not so dramatic as to cause youngsters with the “bad” alleles to inevitably become chain smokers, nor do the right set of genes confer protection against smoking. It’s not that simple. However, the study is definitely one more reason to push aggressive smoking prevention efforts aimed at adolescents.

(First published March 28, 2013)

Belsky D.W. Polygenic Risk and the Developmental Progression to Heavy, Persistent Smoking and Nicotine DependenceEvidence From a 4-Decade Longitudinal StudyDevelopmental Progression of Smoking Behavior, JAMA Psychiatry, 1. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.736

Graphics credit: http://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/

Labels:

cigarettes,

genetic addiction,

nicotine,

smoking,

stop smoking

Monday, November 24, 2014

Why Do Patients With Schizophrenia Smoke So Many Cigarettes?

For sound neurological reasons, that's why.

(Originally published May 2, 2012, by The Dana Foundation)

For mental health workers, it is well known that an overwhelming majority of psychiatric patients diagnosed with schizophrenia are heavy cigarette smokers. Surveys have shown that at least 60 percent of patients exhibiting symptoms of schizophrenia are smokers, compared with a national average that hovers just above 20 percent. Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, researcher Judith J. Prochaska, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California in San Francisco, found that “smokers with serious mental illnesses are dying 25 years sooner, on average, than Americans overall.” And tobacco is one of the reasons why.

Cigarettes, long familiar in institutional settings as a tool for reinforcing desired behavior, are slowly disappearing from state hospitals. “For state inpatient psychiatric facilities responding to surveys,” says Prochaska, “the best estimate is that about half have adopted smoke-free policies.” Increasingly, acute nicotine withdrawal is a strong part of the mix for the recently admitted smoker with schizophrenia.

An earlier study by Prochaska and colleagues, published in Psychiatric Services, found that while 42 percent of psychiatric patients at a smoke-free San Francisco hospital were smokers, averaging slightly more than a pack per day, none of the smokers received a diagnosis of dependence or withdrawal, and none were offered treatment planning for smoking cessation.

“Smokers who were not given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy were more than twice as likely to be discharged from the hospital against medical advice as nonsmokers and smokers who were given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy,” the study concludes. The authors believe that “nicotine withdrawal left unaddressed may compromise psychiatric care…. Given the complicated relationship between mental illness and smoking, integration of cessation efforts into psychiatric care is recommended.”

During the first few hours after patients with schizophrenia enter smoke-free psychiatric emergency settings, more than half become agitated, and 6 percent are physically restrained, according to a recent study by Dr. Michael H. Allen and coworkers at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, the double-blind study looked at 40 patients admitted to the psychiatric emergency service of the Hospital of the University of Geneva, and found that a relatively safe and simple addition to the emergency stabilization of patients with schizophrenia—a 21 mg nicotine patch—markedly reduced agitation in patients who smoked. The practice of “forced abstinence,” which is the consequence of recent trends toward smoke-free institutions, may not be in the patient’s best interest—especially since formal smoking cessation programs are not always a part of hospital routine.

Allen and colleagues gave out either the nicotine patch or a placebo patch to 40 smokers recently admitted to the hospital with symptoms of schizophrenia. While agitation diminished over time in both the intervention group and the placebo group, “the intervention group had a 33 percent greater reduction in agitation at 4 hours and a 23 percent greater reduction at 24 hours.” The authors say that the differences are similar to those observed in industry trials of common antipsychotics. According to Allen, “forced tobacco abstinence may have the effect of increasing aggressive behavior.” For patients with schizophrenia, smoking works.

The importance of nicotine to patients with schizophrenia should not be underestimated. There are rational biological reasons why schizophrenics smoke. A review of earlier studies published in Psychiatric Services suggests that smokers with schizophrenic symptoms may be self-medicating to improve the processing of auditory stimuli, and to reduce the side-effects caused by common antipsychotic medications.

“Neurobiological factors provide the strongest explanation for the link between smoking and schizophrenia,” writes Edward R. Lyon, the study’s author, “because a direct neurochemical interaction can be demonstrated.” Flaws in sensory gating, the process by which the brain lowers its response to a repeated sound, are believed to be involved in the auditory hallucinations common to people with schizophrenia. And sensory gating improves for schizophrenics after they load up on nicotine. Other research has shown a reduction in expression of nicotinic receptors in schizophrenia, suggesting that a susceptibility to smoking and schizophrenia may be related.

“Neurobiological factors provide the strongest explanation for the link between smoking and schizophrenia,” writes Edward R. Lyon, the study’s author, “because a direct neurochemical interaction can be demonstrated.” Flaws in sensory gating, the process by which the brain lowers its response to a repeated sound, are believed to be involved in the auditory hallucinations common to people with schizophrenia. And sensory gating improves for schizophrenics after they load up on nicotine. Other research has shown a reduction in expression of nicotinic receptors in schizophrenia, suggesting that a susceptibility to smoking and schizophrenia may be related.

Prochaska sees smoking among patients in psychiatric settings as the consequence of several factors, including clinicians' failure to treat nicotine addiction, as well as the role nicotine plays as an antidote to drug side effects. Patients are familiar with the side effects of the drugs they take, “so they smoke and it reduces the blood levels of their medications,” she says. “They’re less sedated, and they can focus more.”

This complicates the picture for psychiatric staff: Antipsychotic drugs are metabolized faster in smokers, leading to the need for higher doses of medication. Prochaska notes that tobacco smoke may inhibit the effect of commonly used drugs like haloperidol, and the inhibition “can be as high as an increase clearance of 40–98 percent for olanzapine, a costly medication.”

In an interview, Prochaska said that the heaviest smokers “may need to stay on cessation medications for an extended period, and that’s certainly better for them than smoking. Combination therapy also is recommended. In our studies, we combine the nicotine patch with gum or lozenge so they’re able to add to the patch to get sufficient coverage of withdrawal symptoms.”

Mental health professionals have traditionally argued that patients with schizophrenia do not want to quit smoking, but Prochaska’s work suggests otherwise. Patients in psychiatric settings are about as likely as the general population to want to quit smoking, her research shows. “There is growing evidence that smokers with mental illness are as ready to quit as other smokers and can do so without any threat to their mental health recovery,” she said.

By some estimates, people with psychiatric disorders make up almost half of the current U.S. market for tobacco products. As Prochaska has written, “nicotine dependence is the most prevalent substance use disorder among adult psychiatric patients, and it needs to be placed on the radar of psychiatric practice.”

It’s up to healthcare providers to get the ball rolling. “Many facilities are still struggling with it,” she says. “It’s not been in their purview traditionally, so changing the culture is a big piece of the solution. It’s very much a matter of trying to get tobacco treatment medicalized, having it be automatic, so that nicotine replacement is right there in the admitting orders. And ideally, working with patients while they are hospitalized to motivate smoking cessation, and supporting them when they leave.”

Photo Credit: http://www.ctri.wisc.edu/

Monday, October 20, 2014

The End of Combusted Tobacco?

With E-cigarettes, a mixed bag of possible outcomes.

E-cigarettes represent a controversial and uncertain future for nicotine addiction, and for this reason they have attracted acolytes and naysayers in what feels like equal measure.

It has been almost 8 years since e-cigarette imports first reached our shores, and the FDA’s determination that they are subject to regulation as tobacco products brings the industry to a crucial crossroads.

On the one hand: “Marked interdevice and intermanufacturer variability of e-cigarettes… makes it hard to draw conclusions about the safety or efficacy of the whole device class.”

On the other hand: “Published evaluation of some products suggest that e-cigarettes can be manufactured with levels of both efficacy and safety similar to those of NRT [nicotine replacement therapy] products… they could play the same role as NRT but at a truly national, population scale.”

So which will it be? Is there an outside chance that the decision by the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products will represent the first step in dealing with nicotine products currently “designed, marketed, and sold” outside the regulatory framework established for NRT? A stalemate presently prevails. Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, Drs. David Abrams and Nathan K. Cobb, Johns Hopkins professors affiliated with the American Legacy Foundation, a tobacco research and prevention organization funded with lawsuit money from the major tobacco companies, highlight the irony: In order to market e-cigarettes as smoking cessations devices, manufacturers must seek approval from the FDA to market pharmaceutical products, “an expensive and time-consuming process than no manufacturer has yet attempted.”

Thus, questions about nicotine content, additives of various kinds, and assorted carrier chemicals go unanswered. Yet these are precisely the questions that need answers before e-cigarettes can be viewed as tools in the harm reduction armamentarium. Cobb and Abrams note that current e-cigarettes “represent a single instance of a nicotine product on a shifting spectrum of toxicity, addiction liability, and consumer satisfaction.” But the market dictates that “to compete with and displace combusted tobacco products, e-cigarettes will need to remain relatively convenient, satisfying, and inexpensive,” regulation notwithstanding.

Still, the harm reductionists’ dreams for the product remain seductive, because “surely any world where refined nicotine displaces lethal cigarettes will experience less harm, disease, and deaths? That scenario is one endgame model for tobacco control: smokers flee cigarettes en masse for refined nicotine and ultimately quit all use entirely.”

Critics say fat chance: “As Big Tobacco’s scientists shift from blending leaves and additives to manipulating circuit boards, chemicals, and dosing schedules, they’re unlikely to relinquish their tolerance for risk and toxicity that prematurely kills half their users in their efforts to ensure high levels of customer ‘satisfaction,’ addiction, and retention.”

Once again, it is the dictates of the market that may end up shaping the future of tobacco, and making the plans of harm reductionists look naïve indeed. “Tobacco companies and their investors,” write Cobb and Abrams, “need millions of heavily addicted smokers to remain customers for decades, including a replenishing stream of young people. No publicly traded company could tolerate the downsizing implicit in shifting from long-term addiction to harm reduction and cessation.”

The marketing innovations most likely to stem from tobacco companies entering the market for e-cigarettes are those most likely to “sustain high levels of addiction and synergistic ‘polyuse’ of their existing combusted products,” while simultaneously crimping competition from NRT manufacturers and independent e-cigarette manufacturers. Tobacco companies are past masters at manipulating things like nicotine content, vaporization methodologies, flavorings, and unknown additives. They will surely bring this expertise to bear in seeking a major bite out of the e-cigarette market while maintaining acceptable profit margins on traditional cigarettes.

The authors suggest that the FDA could weight the matter in harm reduction’s favor by using its product-standard authority “to cripple the addictive potential of lethal combusted products by mandating a reduction in nicotine levels to below those of e-cigarettes and NRT products and eliminating flavorings such as menthol that make cigarettes more palatable.” Tax breaks for e-cigarettes would further load the dice.

But not today. The FDA’s proposal calls for warning labels or product safety and quality standards for e-cigarettes—but not for at least two years. Two years is a long time in a fast-emerging market already valued in excess of $2 billion. The authors call the delay disturbing, “given the variability in product quality and a documented spike in cases of accidental nicotine poisoning.”

In conclusion, the authors believe that for smokers hoping to quit, “NRT products still represent safer, more predictable choices, even if they are more expensive and less appealing.”

Photo credit: http://www.rstreet.org/

Labels:

Big Tobacco,

e-cigarettes,

nicotine addiction,

NRT,

stop smoking

Monday, September 22, 2014

The Genetics of Smoking

Evidence from a 40-year study.

(First published March 28, 2013)

Pediatricians have often remarked upon it: Give one adolescent his first cigarette, and he will cough and choke and swear never to try another one. Give a cigarette to a different young person, and she is off to the races, becoming a heavily dependent smoker, often for the rest of her life. We have strong evidence that this difference in reaction to nicotine is, at least in part, a genetic phenomenon.

But so what? Is there any practical use to which such knowledge can be put? As it turns out, the answer may be yes. People with the appropriate gene variations on chromosomes 15 and 19 move very quickly from the first cigarette to heavy use of 20 or more cigarettes per day, and have more difficulty quitting, according to a report published in JAMA Psychiatry. From a public health point of view, these findings add a strong genetic rationale to early smoking prevention efforts— especially programs that attempt to “disrupt the developmental progression of smoking behavior” by means of higher prices and aggressive enforcement of age restrictions on smoking.

What the researchers found were small but identifiable differences that separated people with these genetic variations from other smokers. The gene clusters in question “provide information about smoking risks that cannot be ascertained from a family history, including information about risk for cessation failure,” according to authors Daniel W. Belsky, Avshalom Caspi, and colleagues at the University of North Carolina and Duke University.

The group looked at three prominent genome-wide association studies of adult smoking to see if the results could be applied to “the developmental progression of smoking behavior.” They used the data from the genome work to analyze the results of a 38-year prospective study of 1,037 New Zealanders, known as the Dunedin Study. A total of 405 cohort members in this study ended up as daily smokers, and only 20% of the daily smokers ever achieved cessation, defined as a year or more of continual abstinence.

The researchers came up with a multilocus genetic risk score (GRS) based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with smoking behaviors. Previous meta-analyses had identified several suspects, specifically a region of chromosome 15 containing the CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 gene cluster, and a region of chromosome 19 containing the gene CYP2A6. These two clusters were already strong candidate genes for the development of smoking behaviors. For purpose of the study, the GRS was calculated by adding up the alleles associated with higher smoking quantity. The genetic risk score did not pertain to smoking initiation, but rather to the number of cigarette smoked per day.

When the researchers applied these genetic findings to the Dunedin population cohort, representing ages 11 to 38, they found that an unfortunate combination of gene types seemed to be pushing some smokers toward heavy smoking at an early age. Individuals with a high GRS score “progressed more rapidly to heavy smoking and nicotine dependence, were more likely to become persistent heavy smokers and persistently nicotine dependent, and had more difficulty quitting,” according to the study. However, these effects took hold only when young smokers “progressed rapidly from smoking initiation to heavy smoking during adolescence.” The variations found on chromosomes 15 and 19 influence adult smoking “through a pathway mediated by adolescent progression from smoking initiation to heavy smoking.”

Curiously, the group of people who had the lowest Genetic Risk Scores were not people who had never smoked, but rather people who smoked casually and occasionally—the legendary “chippers,” who can take or leave cigarettes, sometimes have one late at night, or a couple at parties, without ever falling victim to nicotine addiction. These “light but persistent smokers” were accounted for “with the theory that the genetic risks captured in our score influence response to nicotine, not the propensity to initiate smoking.”

Naturally, the study has limitations. Everyone in the Dunedin Study was of European descent, and the life histories ended at age 38. Nor did the study take smoking bans or different ages into account. The study cries out for replication, and hopefully that won’t be long in coming.

Could information of this sort be used to identify high-risk young people for targeted prevention programs? That is the implied promise of such research, but no, probably not. The gene associations are not so dramatic as to cause youngsters with the “bad” alleles to inevitably become chain smokers, nor do the right set of genes confer protection against smoking. It’s not that simple. However, the study is definitely one more reason to push aggressive smoking prevention efforts aimed at adolescents.

Belsky D.W. Polygenic Risk and the Developmental Progression to Heavy, Persistent Smoking and Nicotine DependenceEvidence From a 4-Decade Longitudinal StudyDevelopmental Progression of Smoking Behavior, JAMA Psychiatry, 1. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.736

Graphics Credit: http://neurologicalcorrelates.com/

Labels:

genetics,

nicotine,

smoking,

stop smoking

Saturday, June 28, 2014

Vitamin C and Pregnant Women Who Smoke

Improving pulmonary function in newborns.

500 mg of daily vitamin C given to pregnant smoking women “decreased the effects of in-utero nicotine” and “improved measures of pulmonary function” in their newborns, according to a study by Cindy T. McEvoy and others at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, published in a recent issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

Researchers have long known that smoking during pregnancy can harm the respiratory health of newborns. Maternal smoking during pregnancy can interfere with normal lung development, resulting in lifelong increases in asthma risk and other pulmonary complications. The researchers note that “more than 50% of smokers who become pregnant continue to smoke, corresponding to 12% of all pregnancies.” That adds up to a lot of newborns each year who will start off with more wheezing, respiratory infections, and childhood asthma than their counterparts born to non-smoking mothers.

McEvoy and her colleagues wanted to find out whether a daily dose of vitamin C would improve the results of pulmonary function tests in newborns exposed to tobacco in utero.

It did. In an accompanying editorial, Graham L. Hall calls the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial “well-conceived and executed…. Lung function during the first week of life was statistically significantly better (by approximately 10%) among infants born to mothers randomized to receive Vitamin C compared with infants born to mothers randomized to received placebo.” Moreover, the prevalence of wheezing in the first year was reduced from 40% in the placebo group to 21% in the Vitamin C group.

The decreases in asthma and wheezing in the Vitamin C newborns were documented through the first year of life.

A 10% reduction does not sound like a lot, but, as Hall writes, “small population-level changes in lung function may lead to significant public health benefits, and the improvements in lung function reported here could be associated with future benefit.”

In their paper, the researchers conclude: “Vitamin C supplementation in pregnant smokers may be an inexpensive and simple approach (with continued smoking cessation counseling) to decrease some of the effects of smoking in pregnancy on newborn pulmonary function and ultimately infant respiratory morbidities, but further study is required.”

Pregnant women should not smoke, and quitting is by far the healthiest option. As Hall writes: “By preventing her developing fetus and newborn infant from becoming exposed to tobacco smoke, a pregnant woman can do more for the respiratory health and overall health of her child than any amount of vitamin C may be able to accomplish.”

McEvoy C.T., Nakia Clay, Keith Jackson, Mitzi D. Go, Patricia Spitale, Carol Bunten, Maria Leiva, David Gonzales, Julie Hollister-Smith & Manuel Durand & (2014). Vitamin C Supplementation for Pregnant Smoking Women and Pulmonary Function in Their Newborn Infants, JAMA, 311 (20) 2074. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.5217

Graphics Credit: http://www.quitguide.com/

Thursday, May 8, 2014

Why the CDC Director Hates E-Cigarettes

The pros and cons of getting your vape on.

Last month, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began a new era—regulating e-cigarettes. With a non-controversial first step, the FDA banned the sale of e-cigarettes to minors, required health warnings, prohibited health claims, and outlined a plan to register and license all electronic nicotine products at some future date. The FDA’s proposed rules would also give the agency the power to regulate the currently unregulated mixture of chemicals and flavorings that are heated during e-cigarette use. Whatever regulations the FDA promulgates for electronic cigarettes will also apply to nicotine gels, water pipe tobacco, and hookahs.

Perhaps what rankles e-cigarette activists the most is the FDA’s insistence that companies will have to provide scientific evidence before making any implied claims about risk reduction for their product, compared with cigarettes. The FDA did not restrict advertising or prohibit flavorings (bubble gum, apple-blueberry, gummi bear, and cappuccino are popular).

Within a few days after the FDA’s announcement, Chicago, New York City, and other major cities placed e-cigarettes under the same municipal smoking bans as cigarettes.

The battle over e-cigarettes is both a public health issue and a private enterprise war for market share. Corporate giants Altria and Lorillard, which dominate the corporate tobacco landscape in the U.S., are fighting for a piece of what has become nearly a $2 billion market in a few short years. (Altria recently boosted its growth forecast to 6-9% growth for 2014). Lorillard has been making heavy acquisitions of its own, and commands more than half the present market with its Blu brand. Altria has made its own vapor acquisitions, and is launching its own brand, MarkTen.

So far, the moves being contemplated by the FDA do not have these companies shaking in their boots. They anticipated the ban on sales to minors, a system of formal FDA approval, a disclosure of ingredients, and health warnings about the addictive nature of nicotine. And Congress gave the FDA legal authority to draft a set of rules for e-cigarettes five years ago, so the FDA’s reluctance to step in on liquid nicotine delivery systems has been evident.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Tom Frieden, director of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), listed the reasons for his opposition to electronic cigarettes:

—E-cigarettes are an additional means of hooking another generation of kids on nicotine, making them more likely to become adult smokers.

—Smokers who might have quit smoking will maintain their nicotine addiction, remaining highly vulnerable to tobacco craving.

—Ex-smokers might make themselves more vulnerable to relapse if they take up vaping.

—Smokers might forego medications that could help them quit, in favor of the unproven promise of tobacco abstention via e-cigarette.

—E-cigarettes might have the cultural effect of “re-glamorizing” smoking.

—E-cigarette users might be exposing children and pregnant women to nicotine via secondhand smoke mechanisms.

—E-cigarette users can refill cartridges with liquid cannabis products and other drugs.

Dr. Michael Siegel, a tobacco expert at the Boston University School of Public Health, worries that smaller players will be squeezed out due to costs associated with the FDA approval process, driving sales toward the traditional cigarette industry leaders. Go-go analysts have predicted market penetration of as much as 50% for e-cigarettes, but Siegel is more pessimistic, and believes the e-cigarette share could top out at 10% if FDA regulations set back efforts by vaping proponents to position their product as a safer and healthier alternative to tobacco cigarettes. And that, says Siegel, would be a shame. He told the Boston Globe: “There simply is no product on the market that’s more dangerous than tobacco cigarettes, and nobody in their right mind would argue that cigarette smoking is less hazardous or even equally hazardous to vaping.”

Frieden at the CDC is sympathetic to the fact that many smokers have indeed quit smoking tobacco with the aid of e-cigarettes. “Stick to stick, they’re almost certainly less toxic than cigarettes.” But like many tobacco experts, he sees the possibility of a new generation of nicotine addicts. Almost two million high school kids have tried e-cigarettes, Frieden told the LA Times, “and a lot of them are using them regularly…. That’s like watching someone harm hundreds of thousands of children.” The CDC reported that the percentage of high school students who have used an e-cigarette jumped from 4.7% in 2011 to 10% in 2012. Calls to poison control centers involving children and e-cigarettes have increased sharply as well.

Frieden views the Food and Drug Administration as David under siege by Goliath. The FDA, he said, “tried to regulate e-cigarettes earlier, and they lost to the tobacco industry…. So the FDA has to balance moving quickly with moving in a way that’s going to be able to survive the tobacco industry’s highly paid legal challenge.” If E-cigarette makers really want to market to people trying to quit smoking, Frieden told the LA Times, “then do the clinical trials and apply to the FDA. But they don’t want to do that.” (See my post on Big Tobacco’s move into the e-cigarette market).

“It’s really the wild, wild West out there,” a beleaguered FDA commissioner Margaret Hamburg told the press. “They’re coming in different sizes, shapes and flavors in terms of the nicotine in them.”

On May 4, the New York Times published a report by Matt Richtel, based on an upcoming paper in the journal Nicotine and Tobacco Research. Nicotine researchers discovered that high-end electronic cigarette systems with refillable tanks produce formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, as a component of the exhaled nicotine vapor. Moreover, unlike disposable e-cigarettes, tank systems require users to refill them with liquid nicotine, itself a potent toxin. “Nicotine is a pesticide, fundamentally,” Michael Eriksen, dean of the School of Public Health at Georgia Statue University, told CNN. “We take so many precautions about pesticides for our lawns and how to wear gloves. But what precautions do consumers take when they put the nicotine vials in?”

This was not good news for harm reductionists, who view the advantages of e-cigarettes as self-evident. The New York Times report says that the toxin is formed “when liquid nicotine and other e-cigarette ingredients are subjected to high temperatures,” according to the research. “A second study that is being prepared for submission to the same journal points to similar findings.” In addition, a new study by researchers RTI International documents the release of tiny metal particles, including tin, chromium and nickel, which may worsen asthma and bronchitis.

Eric Moskowitz at the Boston Globe reported that “thousands of gas stations and convenience stores statewide carry e-cigarettes, usually stocking disposable or cartridge-based versions that resemble traditional cigarettes.”

In U.S. News, Gregory Conley, president of the trade group American Vaping Association, predicted “a huge influx of anti-e-cigarette legislation in the last half of 2014 and especially in 2015 when the legislative sessions get going again.”

According to Carl Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond, “it may be years before regulations are imposed. The lobbying at FDA and Congress will be intense.”

Effectively regulated, e-cigarettes have the potential to drastically reduce deaths from tobacco-related diseases among cigarette smokers. In an editorial for the journal Addiction, Sara Hitchman, Ann McNeill, and Leonie Brose of King’s College, London, wrote: “E-cigarettes may offer a way out of the smoking epidemic or a way of perpetuating it; robustly designed, implemented and accurately reported scientific evidence will be the best tool we have to help us predict and shape which of these realities transpires.”

Photo credit: http://ecigarettereviewed.com

Friday, March 14, 2014

The Escalating Debate Over E-Cigarettes

Follow the bouncing ping-pong ball.

“E-cigarettes are likely to be gateway devices for nicotine addiction among youth, opening up a whole new market for tobacco.”

—Lauren Dutra, postdoctoral fellow at the UCSF Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education.

“You’ve got two camps here: an abstinence-only camp that thinks anything related to tobacco should be outlawed, and those of us who say abstinence has failed, and that we have to take advantage of every opportunity with a reasonable prospect for harm reduction.”

—Richard Carmona, former U.S. Surgeon General, now board member of e-cigarette maker NJOY.

“Consumers are led to believe that e-cigarettes are a safe alternative to cigarettes, despite the fact that they are addictive, and there is no regulatory oversight ensuring the safety of the ingredients in e-cigarettes.”

—From a letter to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) signed by 40 state attorneys general.

“E-cigarettes need more time to develop and to out-compete deadly conventional cigarettes, but they have the potential to end the tobacco epidemic. So if regulators decide to ban them or submit them to stricter regulations than conventional cigarettes, this would be detrimental to public health.”

—Professor Peter Hajek, director of the Tobacco Dependence Research Unit at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine.

“There is no scientific evidence that e-cigarettes are a safe substitute for traditional cigarettes or an effective smoking cessation tool. In fact, they may entice young people into trying traditional cigarettes.”

—Russ Sciandra, New York State Director of Advocacy, American Cancer Society.

“I firmly believe that the [New York] City Council’s bill restricting e-cigarettes is a major blow to people who are trying to stop smoking and will end up accomplishing the opposite of advocates’ intended goals of improving people’s health and reducing smoking-related deaths.”

—Tony Newman, director of media relations for the Drug Policy Alliance.

“Once a young person gets acquainted with nicotine, it’s more likely that they’ll try other tobacco products. E-cigarettes are a promising growth area for the tobacco companies, allowing them to diversify their addictive and lethal products with a so-called ‘safe cigarette.’”

—Alexander Prokhorov, head of the Tobacco Outreach Education Program, University of Texas.

“What would constitute a final victory in tobacco control? Must victory entail complete abstinence from e-cigarettes as well as tobacco? To what levels must we reduced the prevalence of smoking? What lessons should be drawn from the histories of alcohol and narcotic-drug prohibition?”

—Amy L. Fairchild, professor of sociomedical sciences, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

Photo Credit: St. Paul Pioneer Press (Chris Polydoroff).

Sunday, November 24, 2013

Built-In Advantages Give Big Tobacco an Edge in E-Cigs

The Big Three are now in it to win it.

If there was ever any doubt that major tobacco companies have designs on the emerging electronic cigarette market, a recent roundup in the Wall Street Journal makes the case with ease, something that eager acolytes of e-cigs are anxious to avoid. No doubt about it, Big Tobacco wants in.

Results from intensive test marketing in Colorado have, like a political primary, provided an early indication of where the popularity lies. Reynolds American, the nation’s 2nd largest tobacco company (Camel), led the, uh, pack with its offering, the Vuse e-cigarette, introduced in July. Vuse racked up a 55% market share in that state. Next in line, with 25%, was Blu, owned by the 3rd largest cigarette maker, Lorillard (Newport). NJOY, an independent company, came in third. The elephant in the room, Altria Group, the largest U.S. tobacco firm (Marlboro), is still in the test marketing stage with its e-cigarette entry, the MarkTen. Altria began testing the MarkTen in Indiana and Arizona in late summer.

It took Reynolds less than 16 weeks to achieve market dominance in Colorado, and the company made sure that investors heard about it. With 1,800 retail outlets in Colorado, and a database of 12 million tobacco consumers, Reynolds is perfectly poised to benefit from the inherent advantages of being Big Tobacco. The Big Three have three major head starts, the Wall Street Journal reported: “extensive distribution networks, existing customer relationships numbering in the millions, and deep pockets.”

The market for electronic cigarettes has broken a billion dollars, say stock watchers. This magic number seems to have energized the Big Three to take a heavy step into a market that has been around in nascent form since 2006, even though it’s still small change compared to the $100 billion U.S. tobacco market. It was not clear, in the beginning, whether Reynolds, Lorillard, and Altria would attempt to, pardon me, snuff out the competition, or dominate it. That decision now appears to have been made, and the game is on.

Stephanie Cordisco, president of R.J. Reynolds Vapor Company, which markets Vuse, said the marketing tagline in Colorado was: “A perfect puff. First time, every time.”

So far, e-cigarettes, which heat nicotine-based liquid to create a vaporized mist, have benefitted from the fact that they are not, at present, savagely taxed like regular cigarettes. And e-cigs come in flavors, cherry and pina colada being among the favorites.

In April of 2012, Lorillard broke the e-cig barrier when it acquired Blu Ecigs for $135 million. At the Wall Street Journal, Mike Esterl suggested that the move came “as the Food and Drug Administration weighs a possible crackdown on menthol-flavored cigarettes, which represent about 90% of revenue at Greensboro, N.C.-based Lorillard, owner of the popular Newport brand. The FDA already has banned all other cigarette flavors.”

Reynolds followed Lorillard into the market early in 2013 with Vuse. And the giant Altria Group announced in October that it planned to expand sales of the MarkTen after successful “lead market” sales. It’s too early too say how it will go for the MarkTen, but Altria CEO Marty Barrington said in a conference call reported by the Richmond Times-Dispatch that the company is not overly worried about cannibalizing Marlboro sales: “I can tell you that with respect to who is trying the products in e-vapor generally,” he said, “ we do know that there is dual use. As adult smokers try e-vapor products, we know that some of them are satisfied and others are not. Some of them use [e-cigarettes] situationally.”

That does not sound like an executive rolling out a stop-smoking therapy tool.

Graphics Credit: http://seekingalpha.com

Labels:

Big Tobacco,

Blu,

e-cigarettes,

electronic cigarettes,

MarkTen,

stop smoking,

Vuse

Saturday, June 22, 2013

Smoking and Surgery Don’t Mix

Even routine operations are riskier for smokers.

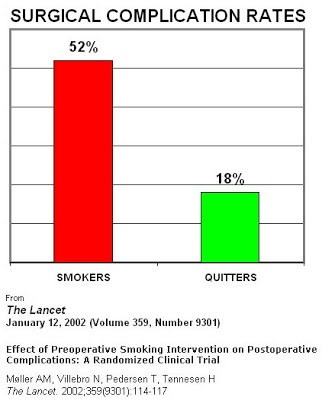

Smokers who are scheduling a medical operation might want to think seriously about quitting, once they hear the results of a new review of the impact of smoking on surgical outcomes.

A scheduled operation is the perfect incentive for smokers to quit smoking. The fact that smokers have poorer post-surgical outcomes, with longer healing times and more complications, is not a new finding. But the study by researchers from the University of California in San Francisco, and Yale University School of Medicine, published in the Journal of Neurosurgery, spells out the surgicial risks for smokers in graphic detail.

Cellular Injury

The systematic effects of nicotine and carbon monoxide in the blood of cigarette smokers result in tissue hypoxia, which is a lack of adequate blood supply caused by a shortage of oxygen. When carbon monoxide floods the bloodstream in high concentrations, as it does in smokers, it is capable of binding with hemoglobin and thus lowering the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. A cascade of physiological reactions then lead to the possibility of low coagulation levels, vasoconstriction, spasms, and blood clots.

Wound Healing and Infection

If the circulatory system is dysfunctional, healing will be impaired. “In addition,” the researchers say, “tobacco may stimulate a stress response mediated by enhanced fibroblast activity, resulting in decreased cell migration and increased cell adhesion. The net consequence is inappropriate connective tissue deposition at the surgical site, delayed wound healing, and increased risks of wound infection.”

Blood Loss

In their review of the neurosurgical literature, the researchers found higher blood loss for smokers particularly following surgery for certain kinds of tumors and for lumbar spine injuries. Smoking causes “permanent structural changes of vessels such as vessel wall thickening,” and there is evidence that smoking is linked to “larger and more vascularized tumors, which may further contribute to intraoperative blood loss during resection.”

Cardiopulmonary Effects

Even smokers who don’t have any chronic conditions associated with smoking are at increased risk during and after surgery. Oxidative damage from smoke can cause “mucosal damage, goblet cell hyperplasia, ciliary dysfunction, and impaired bronchial function,” all of which impedes the ability to expel mucus, which increases the bacterial load, which alters the respiratory immune response, and which ultimately leads to higher rates of postoperative pneumonia in smokers.

The authors of the review note that the evidence is particularly strong in certain specialties: Cranial surgery, spine surgery, plastic surgery, and orthopedic surgery. One randomized clinical trial showed that a 4-week smoking cessation program lead to a 50 relative risk reduction for postoperative complications. Another study showed significant improvement in wound healing when patients abstained from smoking for 6 to 8 weeks prior to surgery. And a third trial of smokers cited in the study showed a major decrease in complications following surgery for the repair of acute bone fractures in patients who quit before surgery.

The authors close by suggesting that the seriousness of surgery can be used to create a “teachable moment” for patients who smoke. Other studies show consistently that “patients tend to be more likely to quit smoking after hospitalization for serious illness.” All of this makes the act of scheduling surgery a perfect point of contact with smokers in medical settings. Clinicians can neutrally lay out the facts of the matter, in a way that truly brings home the health consequences of tobacco.

Lau D., Berger M.S., Khullar D. & Maa J. (2013). The impact of smoking on neurosurgical outcomes, Journal of Neurosurgery, 1-8. DOI: 10.3171/2013.5.JNS122287

Graphics Credit: http://www.ontarioanesthesiologists.ca/

Sunday, June 16, 2013

A Weak Smoker’s Vaccine Might Be Worse Than None

New PET scans show wide responses to antibodies.

One of the brightest hopes of addiction science has been the idea of a vaccine—an antibody that would scavenge for drug molecules, bind to them, and make it impossible for them to cross the blood-brain barrier and go to work. But there are dozens of good reasons why this seemingly straightforward approach to medical treatment of addiction is devilishly difficult to perform in practice.

Last January, health care company Novartis threw in the towel on NicVax, a nicotine vaccine that failed to beat placebos in Phase III clinical trials for the FDA. And back in 2010, a report in the Archives of General Psychiatry demonstrated that a vaccine intended for cocaine addicts only generated sufficient antibodies to dull the effects of the cocaine in 38 percent of the test subjects. Moreover, it proved possible to overcome immunization by upping the cocaine dose, which sounded like an invitation to overdose.

And now, neuroscientists at the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging annual meeting have presented a new study, the conclusions of which might help researchers understand why the vaccine results have been so mixed. The research “represents one of the first human studies of its kind using molecular imaging to test an investigational anti-nicotine immunization,” lead author Alexey Mukhin, professor of psychiatry and behavioral science at Duke University Medical Center, said in a prepared statement.

Subjects underwent two PET brain scan as they smoked nicotine labeled with radioactive C-11, one before the vaccine was administered, and one after. Ten subjects who developed “high-affinity antibodies” after vaccination showed a slight decrease in nicotine accumulation in the brain, as judged by the scans. However, another group of ten subjects, who showed “intermediate serum nicotine binding capacity and low affinity of antibodies” actually showed an increase in brain nicotine levels. What the PET scans showed was that “strong nicotine-antibody binding, which means high affinity, was associated with a decrease in brain nicotine accumulation. When binding was not strong, an increase in brain accumulation was observed.”

If the bond that holds the antibodies to the nicotine molecules is weak, the bond can break during passage through the blood-brain barrier, potentially allowing excess nicotine to flood in. This result, said Mukhin, tell us “we should care about not only the amount of antibody, but the quality of the antibody. We don’t want to have low-affinity antibodies because that can negate the anti-nicotine effects of the vaccination.”

Back to the drawing board? Not entirely. Another of the study authors, Yantao Zuo of Duke University Medical Center, said that “with reports of new generations of the vaccines showing potentially much higher potencies in animal studies, we are hopeful that our current findings and methodology in human research will facilitate understanding of how these work in smokers.”

Photo Credit:http://www.medgadget.com

Labels:

cigarettes,

nicotine,

smoking,

stop smoking,

vaccine

Friday, May 31, 2013

Tuesday, May 14, 2013

Six Arguments For the Elimination of Cigarettes

Prohibition and the “tobacco control endgame.”

Despite all our efforts in recent years to reduce the percentage of Americans who smoke cigarettes—currently about one in five—the idea of full-blown cigarette prohibition has not gained much traction. That may be changing, as prominent nicotine researchers and public police officials start thinking about what is widely referred to as the “tobacco control endgame.”

Considering the new regulatory powers given the FDA under the terms of the Tobacco Control Act of 2009, as a commentary in Tobacco Control framed it, “will the government be a facilitator or barrier to the effective implementation of strategies designed to achieve this public health goal?”

Two newer approaches have gained some traction in the research community: Reduce the level of nicotine in cigarette products (the FDA is prohibited by law from reducing nicotine content to zero), and continuing to emphasize the non-combustible forms. Plus, everybody pretty much agrees on higher prices.

Here are the six arguments for going all the way:

1) Death. Six million of them a year, worldwide, a number that will grow before it starts shrinking. A billion deaths this century, compared to 100 million in the 20th Century. Robert Proctor, author of The Golden Holocaust and a professor of history at Stanford, whose six arguments these are, calls the cigarette “the deadliest object in the history of human civilization.” So there’s that.

2) Other product defects. The cigarette is defective, Proctor writes in defense of his six arguments in Tobacco Control, because it is “not just dangerous but unreasonably dangerous, killing half its long-term users.” Indeed, it is hard to imagine the FDA green-lighting a drug product like that today. In addition, Proctor claims cigarettes are defective because the tobacco has been altered by flue curing to make it far more inhalable than would otherwise be the case. “The world’s present epidemic of lung cancer is almost entirely due to the use of low pH flue-cured tobacco in cigarettes, an industry-wide practice that could be reversed at any time.”

3) Financial burdens. These can be reckoned principally in terms of the costs of treating smoking-related illnesses. This, in turn, leads to diminished labor productivity, especially in the developing world, a process that “in many parts of the world makes the poor even poorer,” Proctor observes.

4) Big Tobacco’s impact on science. By sponsoring shoddy and distracting research, by publishing “decoy” findings and by otherwise confusing and corrupting scientific discourse on the cigarette question in the advertising-dependent popular media. The tobacco industry has proved to everyone’s satisfaction that it can put politicians and regulators under intense pressure to see things its way. Not to mention other institutions that have been “bullied, corrupted or exploited,” according to Proctor: The AMA, The American Law Institute, sports organizations, Hollywood, the military, and the U.S. Congress, for starters. (Until 2011, American submarines were not smoke-free.)

5) Environmental harms. More than you might think falls into this category: Deforestation, pesticide use, loss of savannah woodlands for charcoal used in flue curing, fossil fuels for curing and transport, fires caused by burning cigarettes, etc.

6) Smokers want to quit. Smoking is not a recreational drug, as Proctor takes pains to point out. Most smokers hate it and wish they could quit. This makes cigarettes different from alcohol or marijuana, Proctor insists. He quotes a Canadian tobacco executive, who said that smoking isn’t like drinking; it’s more like being an alcoholic. This rings true to for the majority of addicted smokers I know, and was certainly true of me when I was a smoker.

So there it is, the case for tobacco prohibition. But hasn’t all this prohibition business been tried and found wanting? We know the results of drug and alcohol prohibition, whatever their rationales: Smuggling, organized crime, increased law enforcement, more money. This argument, says Proctor, has been central to the cigarette industry since forever: “Bans are ridiculed as impractical or tyrannical. (First they come for your cigarettes…)”

Proctor’s response is that smuggling is already common, and people should be free to grow tobacco for their personal use. He advocates a ban on sales, not possession.

There are at least two major obstacles to cigarette prohibition. First, an enormous amount of tax revenue is generated by the production and sale of cigarettes. And the troubling question of a steep rise in black marketeering goes largely ignored or unaddressed. In the same special issue of Tobacco Control, Peter Reuter has sobering thoughts on that front: “Cigarette black markets are commonplace in high tax jurisdictions. For example, estimates are that contraband cigarettes now account for 20-30% of the Canadian market, which has restrained government enthusiasm for raising taxes further. All the proposed ‘endgame’ proposals for shrinking cigarette prevalence toward zero run the risk of creating black markets.”

In the end, Proctor argues that the cigarette industry itself has repeatedly promised to quit the business if its products where ever found to be profoundly harmful to consumers. As recently as 1997, Philip Morris CEO Geoffrey Bible swore under oath that if cigarettes were found to cause cancer “I’d probably… shut it down instantly to get a better hold on things.” Incredible statements like this by company executives go back to the 1950s. Perhaps it’s time to let them stop lying. “The cigarette, as presently constituted,” writes Proctor, “is simply too dangerous—and destructive and unloved—to be sold.”

Proctor R.N. (2013). Why ban the sale of cigarettes? The case for abolition, Tobacco Control, 22 (Supplement 1) i27-i30. DOI: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050811

Photo: AAP/April Fonti

Thursday, March 28, 2013

Smokers’ Genes: Evidence From a 4-Decade Study

How adolescent risk becomes adult addiction.

Pediatricians have often remarked upon it: Give one adolescent his first cigarette, and he will cough and choke and swear never to try another one. Give a cigarette to a different young person, and she is off to the races, becoming a heavily dependent smoker, often for the rest of her life. We have strong evidence that this difference in reaction to nicotine is, at least in part, a genetic phenomenon.

But so what? Is there any practical use to which such knowledge can be put? As it turns out, the answer may be yes. People with the appropriate gene variations on chromosomes 15 and 19 move very quickly from the first cigarette to heavy use of 20 or more cigarettes per day, and have more difficulty quitting, according to a new report published in JAMA Psychiatry. From a public health point of view, these findings add a strong genetic rationale to early smoking prevention efforts— especially programs that attempt to “disrupt the developmental progression of smoking behavior” by means of higher prices and aggressive enforcement of age restrictions on smoking.

What the researchers found were small but identifiable differences that separated people with these genetic variations from other smokers. The gene clusters in question “provide information about smoking risks that cannot be ascertained from a family history, including information about risk for cessation failure,” according to authors Daniel W. Belsky, Avshalom Caspi, and colleagues at the University of North Carolina and Duke University.

The group looked at three prominent genome-wide association studies of adult smoking to see if the results could be applied to “the developmental progression of smoking behavior.” They used the data from the genome work to analyze the results of a 38-year prospective study of 1,037 New Zealanders, known as the Dunedin Study. A total of 405 cohort members in this study ended up as daily smokers, and only 20% of the daily smokers ever achieved cessation, defined as a year or more of continual abstinence.

The researchers came up with a multilocus genetic risk score (GRS) based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with smoking behaviors. Previous meta-analyses had identified several suspects, specifically a region of chromosome 15 containing the CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 gene cluster, and a region of chromosome 19 containing the gene CYP2A6. These two clusters were already strong candidate genes for the development of smoking behaviors. For purpose of the study, the GRS was calculated by adding up the alleles associated with higher smoking quantity. The genetic risk score did not pertain to smoking initiation, but rather to the number of cigarette smoked per day.

When the researchers applied these genetic findings to the Dunedin population cohort, representing ages 11 to 38, they found that an unfortunate combination of gene types seemed to be pushing some smokers toward heavy smoking at an early age. Individuals with a high GRS score “progressed more rapidly to heavy smoking and nicotine dependence, were more likely to become persistent heavy smokers and persistently nicotine dependent, and had more difficulty quitting,” according to the study. However, these effects took hold only when young smokers “progressed rapidly from smoking initiation to heavy smoking during adolescence.” The variations found on chromosomes 15 and 19 influence adult smoking “through a pathway mediated by adolescent progression from smoking initiation to heavy smoking.”

Curiously, the group of people who had the lowest Genetic Risk Scores were not people who had never smoked, but rather people who smoked casually and occasionally—the legendary “chippers,” who can take or leave cigarettes, sometimes have one late at night, or a couple at parties, without ever falling victim to nicotine addiction. These “light but persistent smokers” were accounted for “with the theory that the genetic risks captured in our score influence response to nicotine, not the propensity to initiate smoking.”

Naturally, the study has limitations. Everyone in the Dunedin Study was of European descent, and the life histories ended at age 38. Nor did the study take smoking bans or different ages into account. The study cries out for replication, and hopefully that won’t be long in coming.

Could information of this sort be used to identify high-risk young people for targeted prevention programs? That is the implied promise of such research, but no, probably not. The gene associations are not so dramatic as to cause youngsters with the “bad” alleles to inevitably become chain smokers, nor do the right set of genes confer protection against smoking. It’s not that simple. However, the study is definitely one more reason to push aggressive smoking prevention efforts aimed at adolescents.

Belsky D.W. Polygenic Risk and the Developmental Progression to Heavy, Persistent Smoking and Nicotine Dependence

Graphics Credit: http://cigarettezoom.com/

Labels:

addiction genes,

cigarettes,

genetic,

public health,

smoking,

stop smoking,

teen smoking

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)