Overeating, drug abuse, and the D2 receptor.

A genetic variation in the dopamine D2 receptor predisposes women toward obesity, according to a small but potentially significant study published in the October 17 issue of Science.

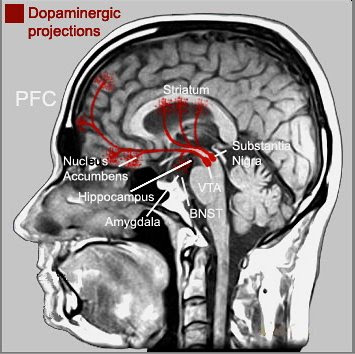

While numerous twins studies demonstrate the likelihood of biological factors in obesity, there are few rigorous studies that back up the contention. Now researchers from Yale University and the University of Texas have used brain scans to show that a dopamine-rich structure called the dorsal striatum exhibits “reduced D2 receptor density and compromised signaling” in obese individuals.

Why would this matter? The dorsal striatum releases dopamine in response to the consumption of tasty food. Going right to the sugary heart of the tasty food cornucopia, the researchers used chocolate milkshakes. Women volunteers underwent MRI scans while researchers administered either squirts of milkshake or squirts of a tasteless liquid. The lower the dopamine response to the milkshake in the dorsal striatum, the more likely the woman was to gain weight over the following year. Reduced dopamine receptor density in the dorsal striatum “may prompt them to overeat in an effort to compensate for this reward deficit,” the study authors concluded. The all-female study lends more evidence to the notion that dopamine D2 variations “are associated with both obesity and substance abuse....”

Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), told Associated Press: “It takes the gene associated with greater vulnerability for obesity and asks the question why. What is it doing to the way the brain is functioning that would make a person more vulnerable to compulsively eat food and become obese?”

Historically, however, the D2 allele has been a controversial locus of research in addiction medicine. In 1990, a research team reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that the A-1 allele controlling production of the dopamine D2 receptor was three times as common in the brains of deceased alcoholics. The aberrant form of the gene was found in 77 per cent of the alcoholics, compared with only 28 per cent of the non-alcoholics. But attempts to replicate the research did not meet with much success. (See Bower, Bruce. “Gene in the Bottle.” Science News, September 21, 1991. p.19). In addition, the findings from the nationwide Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism were not supportive of the D2 hypothesis. (“We believe it doesn’t increase the risk for anything,” one researcher said bluntly.) Well-known researcher Robert Cloninger weighed in with a paper demonstrating that when you broadened the samples and took another look, the D2 connection faded away, suggesting that the D2 allele in question may play a second-order role of some sort. (See Holden, Constance. “A Cautionary Genetic Tale: The Sobering Story of D2.” Science. June 17, 1994. 264 p.1696 ).

The current Science study concludes that “individuals who show blunted striatal activation during food intake are at risk for obesity.... behavioral or pharmacologic interventions that remedy striatal hypofunctioning may assist in the prevent and treatment of this pernicioujs health problem.” NIDA’s Volkow, quoted in the Washington Post, said: “Dieting is a complex process and people don’t like it. Physical activity, which also activates the dopamine pathway, may be a mechanism for reducing the compulsive activity of overeating.”

Dr. Eric Stice of the Oregon Research Institute, the lead scientist on the study, told AP that the findings might have implications for parents. Since most parents don’t know if they possess the suspect variation, Stice suggested than parents could start attending more to the diets of children, “and not get their brains used to having crappy food.”

Photo Credit: Cell Science