Showing posts with label MDMA. Show all posts

Showing posts with label MDMA. Show all posts

Thursday, February 5, 2015

Update on Synthetic Drug Surprises

Spicier than ever.

Four drug deaths last month in Britain have been blamed on so-called “Superman” pills being sold as Ecstasy, but actually containing PMMA, a synthetic stimulant drug with some MDMA-like effects that has been implicated in a number of deaths and hospitalizations in Europe and the U.S. The “fake Ecstasy” was also under suspicion in the September deaths of six people in Florida and another three in Chicago. An additional six deaths in Ireland have also been linked to the drug. (See Drugs.ie for more details.)

PMMA, or paramethoxymethamphetamine, causes dangerous increases in body temperature and blood pressure, is toxic at lower doses than Ecstasy, and requires up to two hours in order to take effect.

In other words, very nearly the perfect overdose drug.

Whether you call them “emerging drugs of misuse,” or “new psychoactive substances,” these synthetic highs have not gone away, and aren’t likely to. As Italian researchers have noted, “The web plays a major role in shaping this unregulated market, with users being attracted by these substances due to both their intense psychoactive effects and likely lack of detection in routine drug screenings.” Even more troubling is the fact that many of the novel compounds turning up as recreational drugs have been abandoned by legitimate chemists because of toxicity or addiction issues.

The Spice products—synthetic cannabinoids—are still the most common of the novel synthetic drugs. Hundreds of variants are now on the market. Science magazine recently reported on a UK study in which researchers discovered more than a dozen previously unknown psychoactive substances by conducting urine samples on portable toilets in Greater London. Call the mixture Spice, K2, Incense, Yucatan Fire, Black Mamba, or any other catchy, edgy name, and chances are, some kids will take it, both for the reported kick, and for the undetectability. According to NIDA, one out of nine U.S. 12th graders had used a synthetic cannabinoid product during the prior year.

“Laws just push forward the list of compounds,” Dr. Duccio Papanti, a psychiatrist at the University of Trieste who studies the new drugs, said in an interview for this article. “The market is very chaotic, bulk purchasing of pure compounds are cheaply available from China, India, Hong-Kong, but small labs are rising in Western Countries, too. Some authors point out that newer compounds are more related to harms (intoxications and deaths) than the older ones. You can clearly see from formulas that newer compounds are different from the first ones: new constituents are added, and there are structural changes, so although we have some clues about the metabolism of older, better studied compounds, we don't know anything about the newer (and currently used) ones."

The problems with synthetic cannabinoids often begin with headaches, vomiting, and hallucinations. At the Department of Medical, Surgical, and Health Sciences at the University of Trieste, researchers Samuele Naviglio, Duccio Papanti, Valentina Moressa, and Alessandro Ventura characterized the typical ER patient on synthetic cannabinoids, in a BMJ article: “On arrival at the emergency department he was conscious but drowsy and slow in answering simple questions. He reported frontal headache (8/10 on a visual analogue scale) and photophobia, and he was unable to stand unassisted. He was afebrile, his heart rate was 170 beats/min, and his blood pressure was 132/80 mm Hg.”

According to the BMJ paper, the most commonly reported adverse symptoms include: "Confusion, agitation, irritability, drowsiness, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis [sweating], mydriasis [excessive pupil dilation], and hallucinations. Other neurological and psychiatric effects include seizures, suicidal ideation, aggressive behavior, and psychosis. Ischemic stroke has also been reported. Gastrointestinal toxicity may cause xerostomia [dry mouth], nausea, and vomiting. Severe cardiotoxic effects have been described, including myocardial infarction…”

In a recent article (PDF) for World Psychiatry, Papanti and a group of other associates revealed additional features of synthetic cannabimemetics (SC), as they are officially known: “For example, inhibition of γ-aminobutyric acid receptors may cause anxiety, agitation, and seizures, whereas the activation of serotonin receptors and the inhibition of monoamine oxidases may be responsible for hallucinations and the occurrence of serotonin syndrome-like signs and symptoms.”

Papanti says researchers are also seeing more fluorinated drugs. “Fluorination is the incorporation of fluorine into a drug,” he says, one effect of which is “modulating the metabolism and increasing the lipophilicity, and enhancing absorption into biological membranes, including the blood-brain barrier, so that a drug is available at higher concentrations. An increasing number of fluorinated synthetic cannabinoids are available, and fluorinated cathinones are available, too.”

A primary problem is that physicians are still largely unacquainted with these chemicals, several years after their current popularity began. This is entirely understandable. In addition to the synthetic cathinones, several new mind-altering substances based on compounds discovered decades ago have also surfaced lately. Papanti provided a partial list of additional compounds that have led to official concern in the EU:

—Synthetic opioids (the best known are AH-7921, MT-45)

—Synthetic stimulants (the best known are MDPV, 4,4'-DMAR)

—New synthetic psychedelics (the NBOMe series)

—New dissociatives (Methoxetamine, Methoxphenidine, Diphenidine)

—New performance enhancing drugs (Melanotan, DNP)

—Gaba agonists (Phenibut, new benzodiazepines)

Most of the new and next-generation synthetics are not readily detected by standard drug screen processes. Spice drugs will not usually show up on anything but the most advanced test screening, using gas chromatography or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry—high tech tools which are rarely available for anything but serious (and costly) forensic investigations.

“Testing is a big problem,” Papanti declares. “From a clinical point of view, do you need the test to make a diagnosis of intoxication, for following up an addiction treatment, or for forensic purposes? With the new drugs, maybe taken together, with different pharmacology, we are not very sure about this yet. If I want to have confirmation of a diagnosis of SC intoxication, I need two weeks as an average, in order to obtain the result. Your patient has been discharged by that time, or in the worse case, he is dead.”

Another major problem, according to Papanti, “is that the machines need sample libraries in order to recognize the compound, and samples mean money. Plus, they need to be continuously updated.”

In summary, there is no antidote to these drugs, but intoxication is general less than 24 hours, and the indicated medical management is primarily supportive. If you plan to take a drug marketed as Ecstasy, or indeed any of the spice or bath salt compounds, Drugs.ie notes that there are some basic rules of conduct that will help maximize the odds of a safe trip:

—If you don’t “come up” as quickly as anticipated, don’t assume you need another pill. PMMA can take two hours or more to take effect. Do not “double drop.”

—If you don’t feel like you expected to feel, and are noticing a “pins-and-needles” feeling or numbness in the limbs, consider the possibility that another drug is involved.

—Don’t mix reputed Ecstasy with other drugs, especially alcohol, as PMMA reacts very dangerously with excessive alcohol.

—Remember to hydrate, but don’t overhydrate. If you go dancing, figure on about a pint per hour.

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

The New Highs: Are Bath Salts Addictive?

Part II.

Call bath salts a new trend, if you insist. Do they cause psychosis? Are they “super-LSD?” The truth is, they are a continuation of a 70-year old trend: speed. Lately, we’ve been fretting about the Adderall Generation, but every population cohort has had its own confrontation with the pleasures and perils of speed: Ritalin, ice, Methedrine, crystal meth, IV meth, amphetamine, Dexedrine, Benzedrine… and so it goes. For addicts: Speed kills. Those two words were found all over posters in the Haight Ashbury district of San Francisco, a few years too late to do the residents much good.

While the matter of the addictiveness of Spice and other synthetic cannabis products remains open to question, there no longer seems to be much doubt about the stimulant drugs known collectively as bath salts. To a greater or lesser degree, these off-the-shelf synthetic stimulants appear to be potentially addictive. And that’s not good news for anyone.

Last week, the U.S. Congress added 26 additional synthetic chemicals to the Controlled Substances Act, including the designer stimulants mephedrone and MDPV, at the behest of the Drug Enforcement

The research news on bath salts at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence (CPDD) in Palm Springs recently was complex and confusing. For example, the phemonenon of overheating, or hyperthermia, that plagues ravers on MDMA and sends some of them to the hospital is a function of certain temperature-sensitive effects of Ecstasy. But it is not as much of a problem with MDPV and mephedrone. The bath salts, like meth, don’t seem to cause overheating as readily.

On another front, William Fantegrossi, assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, told the panel audience that at very high doses and very high temperatures, stimulants like Ecstasy and MDPV “can cause self-mutilation in animals.” Fantegrossi’s statement was the closest anybody has come to providing a possible scientific basis for popular press accounts linking bath salts to flesh-eating frenzies by psychotic users. But this remains speculative, as there are still no reliable toxicological findings available in such cases.

The symposium on bath salts at the CPDD played to a packed conference hall, a sure sign that professional scientists who study addiction for a living were interested in the subject. The panel was titled “A Stimulating Soak in ‘Bath Salts’: Investigating Cathinone Derivative Drugs,” and was co-chaired by Dr. Michael Taffe of the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, CA, and pharmacology professor Dr. Annette Fleckenstein of the University of Utah.

Fantegrossi characterized the overall problem of designer stimulants as “dirty pharmacology” on both sides, pointing to the desperate efforts underway by government-funded scientists to “throw antagonists [blocking drugs] at these things.”

Alexander Shulgin, the grandfather of the modern psychedelic movement, popularized MDMA and hundreds of variants in his backyard laboratory in the Bay Area over the years. Shulgin, better than anyone, knew that legitimate research and dirty recreational chemistry are only a molecule away. In their book Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story, Alexander Shulgin and his wife Ana recall that cartoonist Gary Trudeau captured the truth of the situation as far back as 1985, when the MDMA story became front-page news:

Way back in mid-1985, the cartoonist-author of Doonesbury, Gary Trudeau, did a two-week feature on it, playing it humorous, and almost (but not quite) straight, in a hilarious sequence of twelve strips. On August 19, 1985 he had Duke, president of Baby Doc College, introduce the drug design team from USC in the form of two brilliant twins, Drs. Albie and Bunny Gorp. They vividly demonstrated to the enthusiastic conference that their new drug "Intensity" was simply MDMA with one of the two oxygens removed. "Voila," said one of them, with a molecular model in his hands, "Legal as sea salt."

Jeffrey Moran of the Arkansas Department of Health noted that despite the cat-and-mouse game continuously played between illegal drug designers and the law, government bans on mephedrone and MDPV, the two most common forms of designer stimulant, cause only temporary downturns in supply. They are no longer as legal as sea salt, but it doesn’t seem to matter. There are always new ones in the pipeline. Moran told the audience that at least 48 different compounds had been identified in more than 200 distinct bath salt-style products in his state alone. Sorting out the specific chemistry involves specialized assays designed to detect a bewildering array of molecules: methylone, mephedrone, paphyrone, butylone, 4-MEC, alpha-PVP, and a host of others, some old, some new, some reimagined by underground chemists.

Terry Boos of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency explained that most designer stimulants currently in play are not manufactured stateside. Most originate in Asia and arrive through various ports of call, where they are repackaged for sale in the U.S. Purity of the cathinone ranges from 30 to 95 per cent, Boos said.

Annette Fleckenstein of the University of Utah emphasized that scientists shouldn’t be fooled by overall structural similarities among such drugs as meth, mephedrone, MDMA, and MDPV. In a 2011 study published with her colleagues at the University of Utah, Fleckenstein lamented that mephedrone’s recent emergence on the drug scene had exposed the fact that “there are no formal pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic studies of mephedrone.”

But she has managed to show that methamphetamine causes lasting decreases in serotonin functions, as well as the better-known dopamine alterations, and that MDMA and mephedrone are intimately involved in the accumulation of serotonin in the brain’s nucleus accumbens, where addictive drugs produce many of their rewarding effects. “Rats will self-administer mephedrone,” said Fleckenstein—always a troubling clue that the drug in question may have addictive properties. Since the high in humans only last for three to six hours, there is a tendency to reinforce the behavior through repeated dosings.

Other behavioral clues have been teased out of rat studies. The Taffe Laboratory at Scripps Research Institute has focused on the cognitive, thermoregulatory, and potentially addictive effects of the cathinones. Rats will self-administer mephedrone, MDPV, and of course methamphetamine. However, Dr. Taffe told the audience that MDMA does not produce these classic locomotor stimulant effects at low doses and that it is “more difficult to get them to self-administer” Ecstasy. Nonetheless, Taffe told me he believes that MDMA is, in fact, potentially addictive. “Our data suggest that MDPV is highly reinforcing,” Taffe said in an email exchange after the conference, “and at least as readily self-administered as methamphetamine, at approximately the same per-infusion doses. But it is a very complicated story.”

Scripps researchers have carried the investigation forward with a new study, currently in press at the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Pai-Kai Huang and coworkers studied the differing effects of designer stimulants on voluntary wheel-running activity in rats, adding additional evidence to the basic behavioral split among club drugs of the moment. Taffe, one of the study’s co-authors, said the researchers had predicted that the two drugs with the strongest serotonin activity—MDMA and the mephedrone variants—would decrease wheel running activity in the rats. Methedrine and MDPV, they predicted, would increase activity.

And that’s how it turned out. What that means for human users is still not entirely clear. But MDPV in particular, it now seems evident, has some rather direct and disturbing affinities with crystal meth and cocaine. And the vagaries of the market have led to sharp increases in the percentage of MDPV found in bath salt products in the last two years. Are we seeing the wholesale replacement of MDMA by a more directly addictive, methedrine-like drug? Will we see a rise in psychotic symptoms, and increased visits to the ER, as MDPV becomes more common in bath salts? Ecstasy has been implicated in the death of users as well, but will the surge in cathinone drugs mean there will be additional deaths?

And remember: Researchers are able to distinguish between rats under the influence of either MDMA- or MDPV-based wheel activity—but the research suggests that under blinded conditions, human users aren’t very good at guessing which of those two drugs they’re on. Furthermore, we don’t have the data to say whether users can tell mephedrone from MDPV in a blind test. And even wheel-running rats don’t give away whether they’re running on MDMA or mephedrone. These categorical distinctions are all-important, but still in relative infancy as far as street use is concerned.

The Scripps scientists concluded that their study “underlines the error of assuming all novel cathinone derivative stimulants that become popular with recreational users will share neuropharmacological or biobehavioral properties.” Some of the combinations produce a “unique constellation of desired effects.”

But by 2011, the U.S. media had conflated mephedrone with MDPV and half a dozen other substances, all with differing effects on users. For public health officials, it was a nightmare.

“We know that MDMA users follow the science,” Taffe said, at the close of the bath salts panel. “So information we make available can have a direct effect on public health for those people.” But for bath salt users, the picture is not as clear. Consider, once again, Arkansas’ finding of 30 or 40 different cathinone derivatives, part of a set of 250 distinct chemicals identified in different combinations of bath salt products. “Slight modifications can change the toxicities,” Taffe said. “Abuse liabilities differ between MDMA and different cathinones. They all confer different health risks.”

One of the primary drivers of bath salt usage appears to be the desire to finesse drug-testing programs. And if drug-testing programs are pushing people in the direction of more dangerous, unfamiliar, and addictive substances, then perhaps drug testing is part of the problem rather than the solution.

In the short run, emergency treatment of patients with OD symptoms they attribute to bath salts will remain the same, whether the cathinone in question is mephedrone, MDPV, or some other variant. General emergency-department procedures for stimulant intoxication are standardized. People can suffer cardiac arrest from either MDMA or meth. And people can run very high temperatures with overdoses of any of these stimulants.

Are users listening? Do they believe any of the health warnings this time out, or have there been too many over the years, always strident and hysterical and overinflated?

Huang PK, Aarde SM, Angrish D, Houseknecht KL, Dickerson TJ, & Taffe MA (2012). Contrasting effects of d-methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone, and 4-methylmethcathinone on wheel activity in rats. Drug and alcohol dependence PMID: 22664136

Hadlock GC, Webb KM, McFadden LM, Chu PW, Ellis JD, Allen SC, Andrenyak DM, Vieira-Brock PL, German CL, Conrad KM, Hoonakker AJ, Gibb JW, Wilkins DG, Hanson GR, & Fleckenstein AE (2011). 4-Methylmethcathinone (mephedrone): neuropharmacological effects of a designer stimulant of abuse. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics, 339 (2), 530-6 PMID: 21810934

Labels:

4-MMC,

bath salts,

cathinones,

designer stimulant,

MDMA,

MDPV,

mephedrone,

meth,

methamphetamine

Thursday, June 21, 2012

The Low Down on the New Highs

Not all bath salts are alike.

“You’re 16 hours into your 24-hour shift on the medic unit, and you find yourself responding to an “unknown problem” call.... Walking up to the patient, you note a slender male sitting wide-eyed on the sidewalk. His skin is noticeably flushed and diaphoretic, and he appears extremely tense. You notice slight tremors in his upper body, a clenched jaw and a vacant look in his eyes.... As you begin to apply the blood pressure cuff, the patient begins violently resisting and thrashing about on the sidewalk—still handcuffed. Nothing seems to calm him, and he simultaneously bangs his head on the sidewalk and tries to kick you... and his body temperature is 103.2° F. He doesn’t respond with anything other than basic “yes” and “no” answers. Recognizing the probable state of acute stimulant intoxication and the risks associated, you begin further treatment. You turn the patient compartment air conditioning on high and obtain large-bore IV access of normal saline and set an initial infusion rate of 250 cc/hour.... Later in your shift, you return to the same emergency department (ED) and are informed that the patient has been admitted for rhabdomyolysis and has admitted to taking “bath salts” for the past three days.”

This episode, taken from an article in a recent issue of the Journal of Emergency Medical Services by Jon Nevin, a California emergency medical technician and paramedic, aptly demonstrates the dilemmas facing medical workers since the explosion in usage of “bath salts.” A catchall category for a family of designer stimulants centered on chemicals known as cathinones, bath salts, which are of course no such thing, began filtering in from Europe. One of the more popular new club drugs was variously called meph, or CAT, or 4-MMC, or Meow Meow. The drug’s official name was mephedrone. It was a chemical cousin of amphetamine, with effects somewhat similar to those of Ecstasy (MDMA).

In 2011, calls to poison controls centers skyrocketed across the country as new and untested combinations of cathinones came on the market. Bewildered emergency room technicians and toxicologists were hard pressed to identify even basic ingredients. Recreational users never knew what was in the shiny foil packages, only what was purportedly not in them—a laundry list of recently proscribed chemicals, which the marketers proudly noted on the packaging. This endless Mobius strip of designer stimulant development and grey-market sales channels mean a lucrative hit-and-run business for the producers, but a completely unsafe landscape for recreational users, who act as voluntary guinea pigs for new combinations of poorly understood psychoactive compounds. It is from this underground designer milieu that MDMA came to the forefront, courtesy of clandestine work done by neurochemist Alexander Shulgin and associates.

Mephedrone started showing up in the U.S. in 2010, and quickly spread via word of mouth and the Internet. This was not the synthetic marijuana in powder form being marketed as Spice and K2, although distribution channels were often the same. This was synthetic speed that could be dissolved and injected. The idea was, you could get high and still pass a random drug test, since drug tests didn’t have the sophisticated assays needed to sort out the cathinones. And you could escape the tightening net around Ecstasy use, and still get Ecstasy-like effects. And designer stimulants picked up another strong user base: heroin addicts and methadone users looked for a detection-free boost. They could stay enrolled in their methadone program, and dodge trouble with parole officers, and still party all weekend on bath salts. One big problem became apparent straightaway: The effect of bath salts varied wildly, from gentle stimulant to some sort of death’s-head equivalent of the brown acid at Woodstock.

Bath salts were easy to buy. These unregulated stimulants came in a bewildering array of mixtures, featuring dozens of ingredients and additives. Even when they weren’t blatantly available on the shelves of head shops and convenience stores, many outlets carried them—if you knew the street codes. What law enforcement officer would bust you for buying jewelry cleaner, for example? Cops and drug enforcement officers must long for the clarity of the old days. You had smack, you had crack, you had bathtub Methedrine (methamphetamine).

“Understanding what each of those substances can do physiologically is key to understanding their dangers and to determining how best to treat people who need medical assistance,” wrote Marc Kaufman, with the McLean Imaging Center at Harvard. The trouble is, that knowledge is hard to come by.

It's not hard to understand the allure of stimulants, designer or otherwise. Countless baby boomers and Gen Xers have sampled cocaine and methamphetamine on a recreational basis, and will have no trouble explaining the appeal: It just feels good. In the short run, these drugs boost self-esteem, physical stamina, locomotor skills, and verbal dexterity. The original Dr. Feelgood of New York hipster fame was injecting his ultracool clientele with amphetamines. Nothing felt better than speed, if you want to put it that way.

Cathinones, like methedrine and other form of speed, are primarily dopamine-active drugs. Though they are now illegal in the U.S., they were formerly of primary interest only to pharmaceutical researchers. The best-known cathinone sold as bath salt—mephedrone—has both dopamine and serotonin effects. It broke big in the UK a few years ago as a “legal” party drug alternative to MDMA. Mephedrone came packaged with other chemicals under various marketing guises. And soon, as legal heat came down on the drug, designers switched to near-beer variants, and eventually began flooding the bath salt markets with other cathinone drugs whose effects were equally murky. Users of bath salt products had been seduced, wrote Natasha Vargas-Cooper in Spin magazine, by the idea that they could “get high without testing dirty.”

In 2011, users of bath salt products started turning up in ERs in significant numbers. Some of them were suffering overdoses of MDMA or mephedrone, but last year a new twist on the cathinone molecular structure began to get serious traction in the states. To stay one jump ahead of the law, underground chemists began churning out large quantities of a different amphetamine variant with the tongue-twisting name of methylenedioxypyrovalerone: MDPV, for short. And what were EMTs and paramedics seeing in cases where the drug could be identified as MDPV? In a study in Clinical Toxicology of recent admissions involving self-reports of bath salt use, two regional poison centers reported that exposure to MDPV was becoming more common than mephedrone. And the clinical symptoms of overdose? Agitation, tachycardia, hallucinations, combative behavior, hypertension, chest pain, blurred vision—and at least one death. This synthetic cathinone was evidently capable of producing psychotic episodes requiring sedation. It all sounded eerily similar to the PCP overdoses of the 60s and 70s, when that dissociative veterinary anesthetic enjoyed a period of dubious notoriety.

The arrival of MDPV in the emergency rooms of American changed the picture considerably. Medical workers and drug enforcement officers were forced to admit that they were behind the rolling curve of drug permutations. Nobody knew what was in a given packet of bath salts or plant food, or whatever other disguise was in vogue this week. Nobody knew how much to take, or to determine how much had been taken. Doctors didn’t know enough about cathinones to consistently diagnose an overdose. And what little testing was available for detecting synthetic stimulants was costly and questionable.

As 2012 began, researchers around the world were feeling pressure to find ways of discriminating between the different kinds of cathinones involved in overdoses, as a way of beginning to seriously sort out the fact from the fiction, the dangers from the overblown scare stories.

Various hopeless phrases were bandied about to describe the task of the DEA’s Forensic Sciences labs—“Whack-a-Mole,” “Cat-and-Mouse,” and “losing battle” being among the most common. What has them baffled and demoralized is the fact that these new chemicals under the sun are being created by underground chemists with more than casual kitchen sink skills. And, as one undercover drug officer told Spin Magazine, “when you go out and seize a warehouse full of something packaged as Dragonfly, you really have no idea what it is.” Nor do you know whether you can make a case under the Federal Analog Act, which is supposed to make all this easier by allowing cops and courts to outlaw drugs that are “substantially similar” to drugs already proscribed. But deciding questions of that nature is a matter of sophisticated biochemistry.

Dr. Michael Taffe of the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, CA, and pharmacology professor Annette Fleckenstein of the University of Utah have been working on these questions in the lab. Building on previous work, they had begun to conclude from their own animal studies that when it came to cathinones, there could be a big difference in effect without much evidence of a difference in chemistry.

Taffe and Fleckenstein, working separately, had produced evidence of specific behavioral differences between mephedrone and MPDV. As co-chairs of what turned out to be one of the best-attended sessions at the recent annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence, the two scientists proceeded to expand the general understanding of a drug running rampant across three continents, and previously associated only with the chewing of Khat, a mild stimulant plant found in Africa.

(End of Part I)

Graphics Credit: http://www.bytrade.com/

Labels:

bath salts,

club drug,

designer stimulant,

MDMA,

MDPV,

mephedrone,

synthetic stimulants

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

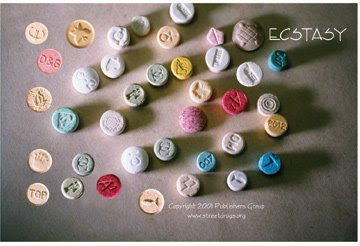

What's in That X Pill, Ravers?

Ecstasy comes loaded with other drugs.

I'm not a huge fan of infographics, mostly because they tend to overpromise and are often marred by factual errors. But this one sticks to basics, and reminds kids that pure MDMA is not the play here. Familiar with dibenzylpiperazine? How about 5-MEO-DIPT? Good old methamphetamine you know—but do you want your Ecstasy, itself an amphetamine spinoff, springloaded with an extra dose of it? Scroll down for pictures of "dirty rolls."

Via Recovery Connection

View More Addiction Related Infographics

I'm not a huge fan of infographics, mostly because they tend to overpromise and are often marred by factual errors. But this one sticks to basics, and reminds kids that pure MDMA is not the play here. Familiar with dibenzylpiperazine? How about 5-MEO-DIPT? Good old methamphetamine you know—but do you want your Ecstasy, itself an amphetamine spinoff, springloaded with an extra dose of it? Scroll down for pictures of "dirty rolls."

Via Recovery Connection

View More Addiction Related Infographics

Labels:

dirty roll,

ecstasy,

MDMA,

methamphetamine,

rave,

rave drugs,

ravers,

x

Sunday, April 1, 2012

Interview with Cognitive Neuropsychologist Keith Laws

LSD, E, CBT, and “Mind-Pops.”

Our latest participant in the “Five Question Interview” series is Dr. Keith Laws, professor of cognitive neuropsychology and head of research in the School of Psychology at the University of Hertfordshire, UK. Dr. Laws holds a Ph.D. from the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Cambridge, and is the author of Category-Specificity: Evidence for Modularity of Mind. He has written extensively on cognitive deficits resulting from certain types of neurological injury, and has won several awards for his research on cognitive functioning in schizophrenia. He also maintains an active interest in the challenges of functional brain imaging. Professor Laws is frequently quoted in the British media, and is the author of more than 100 peer-reviewed articles. He is a Chartered Psychologist and an Associate Fellow of the British Psychological Society. And recently, Professor Laws became a blogger, launching the LawsNeuroBlog. He maintains a web homepage, and is virtually unbeatable in the category of obscure British rock trivia.

1. LSD is back in the news, with a rehash of several old studies on acid and alcoholism. A lot of people would like to revive research interest in LSD, MDMA, magic mushrooms, and other psychedelics. What’s your view?

Keith Laws: Yes, “re-hash” is an appropriate phrase—we are witnessing a rebranding of “counter-culture” as “over-the-counter-culture.” The history of LSD research is frequently retold as if grand therapeutic advances were halted because hostile governments criminalised LSD. The bottom-line, however, is that most studies of the 50s and 60s produced little worthy of further scientific pursuit. The recent meta-analysis of 60s studies examining whether LSD reduces “alcohol misuse” is a case in point.

That meta-analysis consisted of 6 trials—none of which produced a significant effect, but their total pooled effect suggested some impact on alcohol misuse. In my recent post on this study, I highlighted a series of points, including: how it is likely that further negative studies have been gathering dust in the file drawers of researchers over the years; how some samples consisted of people with serious comorbid mental health and neurological problems (schizophrenia, epilepsy, organic brain disorder, low IQ); and crucially, how the authors made the totally unfounded assumption that anyone dropping-out of the studies had relapsed into drinking. This had a large and disproportionate impact on the control samples in those studies—as many more dropped out from control groups. Combined with the lack of significant effects in any one study, doubts exist about relying on these data as a justification for starting large-scale trials of LSD for alcoholism. We should certainly skeptically regard statements by some, such as Professor David Nutt, that LSD is “as good as anything we’ve got for treating alcoholism.”

2. Tell us about your research interest in the effect of Ecstasy (MDMA) on memory.

Keith Laws: First, I think its crucial not to confuse E and MDMA. Studies of MDMA in humans are few, and mostly examine acute effects via self-report. The vast majority of studies though, including our work, examine the residual effects of street-E in abstinent users i.e. taking largely unknown compounds mixed with varying degrees of MDMA. For me, the real public health issue relates to street-E since most people outside of the lab rarely get to consume pure MDMA.

In 2007 we meta-analysed 26 studies that had examined memory on standardized tests in over 600 ecstasy users and 600 non-users and found significant long and short-term verbal memory impairments in 75% of users. Intriguingly, E was unrelated to visual memory problems; however those who also smoked cannabis did display significant visual memory impairment. A key finding of ours was that the lifetime number of E tablets consumed was unrelated to the degree of memory impairment. This led to a host of misrepresentations in the media and amongst E users who saw it as license to take as many Es as they want. I view this finding, however in a much starker light—taking E is akin to playing Russian Roulette with your memory. Some may tolerate 100s or even 1000s of E tablets, but for others far fewer may lead to memory problems—we can predict that 3 in 4 users will develop memory problems, but not which 3 or after how many tablets. Of course, ecstasy (like Cannabis) is often advocated as a safe-ish drug because it rarely kills. Indeed, metrics of drug harm developed in the UK emphasise physical and social harm, but fail to explicitly acknowledge the cognitive problems associated with E and other recreational drugs. Given that as many as 500,000 young people in the UK use E each week and 75% are affected, then that’s 375,000 young people developing significant verbal memory problems!

3. You’re not convinced by the findings of a recent study of magic mushrooms, where the researchers documented an overall decrease in brain activity. What else could account for this effect?

Keith Laws: Well, the surprising thing about the Carhart-Harris et. al. psilocybin study was the general pattern of brain deactivation, which contrasts with the findings of activation in others such as Vollenweider and colleagues in Switzerland who find increased activation. The decreased activation especially in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) were curious and reminded me of the similar deactivation in these areas linked both to anxiety and to the anticipation of unpleasant events. It occurred to me that the prospect of tripping in a scanner may be quite anxiety provoking, and several features of the study led to me to think this may have been the case. First the order of testing was always the same - participants received the placebo scan always before the psilocybin scan and so, could always anticipate the trip— potentially heightening anxious anticipation in that condition. Second, Carhart-Harris et. al. measured “anxiety” and “fear of losing one’s mind” and both multiplied many fold in the psilocybin condition. Interestingly and subsequently, Vollenweider and colleagues pooled date from 23 studies and found that experimental settings involving scanning most strongly predicted unpleasant and/or anxious reactions to psilocybin - converging directly on my suspicion. Although nobody would deny that hallucinogens such as psilocybin impact brain function - the question is which parts reflect the “trip” and which parts reflect “anxiety about the trip”?

4. You have also looked at the matter of using cognitive behavioral therapy for various kinds of mental disorders. How does CBT measure up, in your opinion? Is it useful for addiction?

Keith Laws: Yes, unlike any other country, the UK endorses using CBT to treat psychotic symptoms and to prevent relapse in schizophrenia. Indeed, “NICE” (the National Institute of Clinical Excellence), which decide which treatments are made available to UK patients, suggest that we offer CBT to “all people with schizophrenia”. Anyway, we meta-analysed the data for whether CBT reduces symptomatology or prevents relapse and came to the conclusion that the evidence supports neither. Crucially, CBT only appeared to “work” when the therapists were not blind at outcome assessment i.e. they knew to which group the patient was assigned (CBT or control)! The irony is that CBT therapists sing the mantra of evidence-based practice!

In terms of the use of CBT in people with substance abuse problems, it produces a small impact on abstinence with opiates, stimulants and cocaine, but has little or impact on alcohol use; and as one might expect, these effects disappear across time. Some evidence also suggests that women respond better to CBT than men. Perhaps the most intriguing finding in this area is that CBT has had much greater success in reducing cannabis use, with up to 80% showing significant reduction in use.

5. What else have you been investigating recently? What are you excited about?

Keith Laws: Over the past 3 years or so I have been doing more work with individuals suffering from the obsessive compulsive syndrome of disorders i.e. OCD, Body Dysmorphic Disorder, Trichotillomania, Schizo-Obsessive disorder, Tourette’s, and Perfectionism. Our work is looking at phenotypes that might be expressed through this range of disorders and in their first-degree unaffected relatives.

Other things we are working on include what we call “Mind-Pops”—those little thoughts, words, images, or tunes that suddenly pop into your mind at unexpected times and are totally unrelated to your current activity—described long ago by novelists such as Marcel Proust and Vladimir Nabokov. We have just published a paper showing that verbal hallucinations, the core symptom of schizophrenia, may be related to the mind-pop phenomenon that almost everybody experiences, but just manifests itself in a different way.

Labels:

"E",

cbt,

ecstasy,

Keith Laws,

LSD,

magic mushrooms,

MDMA,

neuropsychology

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

MDMA Likes It Hot

X and ambient air temperature.

One of the enduring mysteries about MDMA, the popular amphetamine derivative known as Ecstasy, or X, is the relationship between the drug and ambient air temperature. Why are raves hot, sweaty, and full of loud music and flashing lights? Because “human subjects report a higher euphoric state when taking the drug in sensory rich environments,” according to researchers. So there’s a reason for all those glow sticks and speaker stacks. But is it something inherent in the mechanism of the drug—or simply the overheated party atmosphere combined with vigorous dancing—that can sometimes raise a ravers’ body temperature to dangerous levels?

Drug researchers have known for some time that Ecstasy and high temperature are somehow interlinked. Animal studies have produced strong evidence that a heated environment can cause an increase in MDMA-stimulated serotonin 5-HT response. Many ravers take steps to prevent hyperthermia, or overheating, by regularly drinking water and coming off the dance floor at regular intervals. Most people have heard of hypothermia, a condition in which body temperature drops to dangerously low levels. But hyperthermia can be just as deadly, and it is a common emergency room complaint in MDMA admissions.

In animal models, rats on MDMA (they like it enough to self-administer) show significantly elevated responses to serotonin in the nucleus accumbens at high room temperatures. What does that mean? What goes up must come down: It opens the door to possible serotonin depletion, which can cause dysfunctions in mood and cognition. Researchers at the University of Texas in Austin have found that in rodents, “the magnitude of the hyperthermic response has been tightly correlated with MDMA-induced 5-HT depletion in various brain regions.” The question they pose is whether “elevated ambient temperatures, such as those encountered in rave venues, can exacerbate MDMA-induced temperature-increasing effects and the likelihood of adverse drug effects.” (Cocaine has temperature-related effects as well. When the ambient air temperature is higher than 75 degrees F, accidental cocaine overdoses increase.)

Ecstasy boosts dopamine as well. The Texas researchers suggest that “the combined enhancement of 5-HT and dopamine may contribute to MDMA’s unique effects on thermoregulation.” They also found that core temperature responses appeared to be “experience-dependent,” meaning that rats didn’t show significantly elevated core temperatures in warm rooms until after they had rolled with MDMA at least ten times. And the worse it gets, the worse it gets, according to the report, published in European Neuropsychopharmacology: “Our results suggest that a heated environment facilitates MDMA-induced disruption of homeostatic thermoregulatory responses, but that repeated exposure to MDMA may also disrupt thermoregulation regardless of ambient temperature.”

So, while all that sweaty dancing amps up the perceptual effects of Ecstasy, it isn’t necessarily implicated in overheating. To simulate a nightclub full of X-ed out ravers, investigators at the Scripps Research Institute tested rats on MDMA while the animals exercised on activity wheels. Writing in Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, the researchers found that “wheel activity did not modify the hyperthermia produced…. These results suggest that nightclub dancing in the human Ecstasy consumer may not be a significant factor in medical emergencies.”

Bottom line: Although we have a reasonable idea of how it works in animals, we don’t really know how much of that knowledge applies to humans in rave settings. Research aimed at teasing out the specifics of temperature-related responses to MDMA is ongoing. And it does matter. Frequent heat-induced responses could lead to prolonged 5-HT depletion, which is suspected of causing an escalation of drug intake in experienced Ecstasy users. And frequent, escalating use of MDMA is implicated in a long roster of potential cognitive impairments.

Photo Credit: http://electricchildren.com

Labels:

ecstasy,

hyperthermia,

MDMA,

rave,

serotonin serotinin depletion,

x

Sunday, March 18, 2012

“Bath Salts” and Ecstasy Implicated in Kidney Injuries

“A potentially life-threatening situation.”

Earlier this month, state officials became alarmed by a cluster of puzzling health problems that had suddenly popped up in Casper, Wyoming, population 55,000. Three young people had been hospitalized with kidney injuries, and dozens of others were allegedly suffering from vomiting and back pain after smoking or snorting an herbal product sold as “blueberry spice.” The Poison Review reported that the outbreak was presently under investigation by state medical officials. “At this point we are viewing use of this drug as a potentially life-threatening situation,” said Tracy Murphy, Wyoming state epidemiologist.

It is beginning to look like acute kidney injury from the newer synthetic drugs may be a genuine threat. And if that wasn’t bad enough, continuing research has implicated MDMA, better known as Ecstasy, as another potential source of kidney damage. Recreational druggies, forewarned is forearmed.

Bath salts first. In the Wyoming case, while the drug in question may have been one of the synthetic marijuana products marketed as Spice, it’s entirely possible that the drug in question was actually one or more of the new synthetic stimulants called bath salts. (Quality control and truth in packaging are not part of this industry). The  American Journal of Kidney Diseases recently published a report titled “Recurrent Acute Kidney Injury Following Bath Salts Intoxication.” It features a case history that Yale researchers believe to be “the first report of recurrent acute kidney injury associated with repeated bath salts intoxication.” The most common causes for emergency room admissions due to bath salts—primarily the drugs MDPV and mephedrone—are agitation, hallucinations, and tachycardia, the authors report. But the case report of a 26-year old man showed recurrent kidney injury after using bath salts. The authors speculate that the damage resulted from “severe renal vasospasm induced by these vasoactive substances.” (A vasoactive substance can constrict or dilate blood vessels.)

American Journal of Kidney Diseases recently published a report titled “Recurrent Acute Kidney Injury Following Bath Salts Intoxication.” It features a case history that Yale researchers believe to be “the first report of recurrent acute kidney injury associated with repeated bath salts intoxication.” The most common causes for emergency room admissions due to bath salts—primarily the drugs MDPV and mephedrone—are agitation, hallucinations, and tachycardia, the authors report. But the case report of a 26-year old man showed recurrent kidney injury after using bath salts. The authors speculate that the damage resulted from “severe renal vasospasm induced by these vasoactive substances.” (A vasoactive substance can constrict or dilate blood vessels.)

A possible secondary mechanism of action for kidney damage among bath salt users is rhabdomyolysis—a breakdown of muscle fibers that releases muscle fiber contents into the bloodstream, causing severe kidney damage. Heavy alcohol and drug use, especially cocaine, are also known risk factors for this condition. The complicating factor here is that rhabdomyolysis has also been described in cases of MDMA intoxication, and here we arrived at the second part of the story.

In 2008, the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology published “The Agony of Ecstasy: MDMA and the Kidney.” In this study, Garland A. Campbell and Mitchell H. Rosner of the University of Virginia Department of Medicine found that “Ecstasy has been associated with acute kidney injury that is most commonly secondary to nontraumatic rhabdomyolysis but also has been reported in the setting of drug-induced liver failure and drug-induced vasculitis.”

Chemically, MDMA is another amphetamine spinoff, like mephedrone and other bath salts. Many people take this club drug regularly without apparent harm, whereas others seem to be acutely sensitive and can experience serious toxicity, possibly due to genetic variance in the breakdown enzyme CYP2D6. The authors trace the first case report of acute kidney injury due to Ecstasy back to 1992, but “because most of these data are accrued from case reports, the absolute incidence of this complication cannot be determined.”

Campbell and Rosner believe that nontraumatic rhabdomyolysis is a likely culprit in many cases, and speculate that the condition is “greatly compounded by the ambient temperature, which in crowded rave parties is usually elevated.” If a physician suspects rhabdomyolysis in an Ecstasy user, “aggressive cooling measures should be undertaken to lower the patient’s core temperature to levels that will lessen further muscle and end-organ injury.” This complication can have far-reaching effects: The authors note the case history of “transplant graft loss of both kidneys obtained from a donor with a history of recent Ecstasy use.”

In addition, there may be undocumented risks to the liver as well. An earlier study by Andreu et. al. claims that “up to 31% of all drug toxicity-related acute hepatic failure is due to MDMA… Patients with severe acute hepatic failure secondary to ecstasy use often survive with supportive care and have successfully undergone liver transplantation.”

But the picture is far from clear: “Unfortunately, no case reports of acute kidney injury secondary to ecstasy have had renal biopsies performed to allow for further elucidation…” And attributing firm causation is difficult, due to the fact that MDMA users often use other drugs in combination, some of which, like cocaine, can cause kidney problem all by themselves.

A study by Harold Kalant of the University of Toronto’s Addiction Research Foundation, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, proposed that “dantrolene, which is a drug used to stop the intense muscle contractures in malignant hyperthermia, should also be useful in the hyperthermic type of MDMA toxicity. Numerous cases have now been treated in this way, some with rapid and dramatic results even when the clinical picture suggested the likelihood of a fatal outcome.”

Adebamiro, A., and Perazella, M. (2012). Recurrent Acute Kidney Injury Following Bath Salts Intoxication American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 59 (2), 273-275 DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.012

Graphics Credit: http://trialx.com

Labels:

bath salts,

ecstasy,

kidney damage,

kidney injury,

MDMA,

mephedrone,

rhabdomyolysis

Monday, May 24, 2010

X-ed Out.

Another look at MDMA and serotonin.

A study by Canada’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) has confirmed earlier findings that chronic users of ecstasy (MDMA) have abnormally low levels of serotonin transporter molecules in the cerebral cortex.

While a decade of research on the effects of ecstasy on brain serotonin has been controversial and largely inconclusive, the latest study used drug hair analysis to  confirm levels of MDMA in 49 users and 50 controls. An additional division was made between chronic X users who also tested positive for methamphetamine, and those who did not. Regular usage of MDMA was defined as two tablets twice a month.

confirm levels of MDMA in 49 users and 50 controls. An additional division was made between chronic X users who also tested positive for methamphetamine, and those who did not. Regular usage of MDMA was defined as two tablets twice a month.

The Canadian study, funded by the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and published in the journal Brain, suggests that the serotonin surge responsible for ecstasy’s effects results in a net depletion in regular X users. That is not a new finding--but the Canadian study goes further, suggesting that the serotonin depletion is localized in one area of the brain.

“We were surprised to discover that SERT was decreased only in the cerebral cortex and not throughout the brain,” said study leader Stephen Kish in a press release, “perhaps because serotonin nerves to the cortex are longer and more susceptible to changes.”

Low serotonin transporter (SERT) levels in the cerebral cortex were found in all X users, with or without amphetamine. Dr. Kish noted that the CAMH findings replicate what Kish referred to as “newer data” from Johns Hopkins University. In 1999, a controversial serotonin study of ecstasy users at Johns Hopkins laboratory was criticized for overestimating the level of danger posed by ecstasy-induced serotonin impairments.

Okay, the finding is becoming more robust. But what does it mean? According to co-author Isabelle Boileau, a low SERT level does “not necessarily” indicate structural brain damage. “There is no way to prove whether low SERT is explained by physical loss of the entire serotonin nerve cell, or by a loss of SERT protein within an intact nerve cell.”

For his part, Dr. Kish indicated that his concerns centered on the connection between lower serotonin measurements and MDMA tolerance levels. “Most of the ecstasy users of our study complained that the first dose is always the best, but then the effects begin to decline and higher doses are needed,” he said. “The need for higher doses, possibly caused by low SERT, could well increase the risk of harm caused by this stimulant drug.” The published study concluded that “behavioural problems in some ecstasy users during abstinence might be related to serotonin transporter changes limited to cortical regions.”

However, in addition to the confounding variable of methamphetamine (see my post, “How Pure is Ecstasy?”), it remains unclear whether the SERT alterations detected in the study are transient or permanent. Moreover, the nature of the link that “might” exist between lower SERT levels and cognitive impairment in the brains of regular ecstasy users remains a subject of dispute in the drug research community, as in this earlier post. (And just to emphasize that drugs are complicated things, a spate of promising recent research has suggested that ecstasy might be an effective option for treating people with post-traumatic stress disorder).

The CAMH, affiliated with the University of Toronto, is Canada’s largest mental health and addiction teaching hospital.

Kish, S., Lerch, J., Furukawa, Y., Tong, J., McCluskey, T., Wilkins, D., Houle, S., Meyer, J., Mundo, E., Wilson, A., Rusjan, P., Saint-Cyr, J., Guttman, M., Collins, D., Shapiro, C., Warsh, J., & Boileau, I. (2010). Decreased cerebral cortical serotonin transporter binding in ecstasy users: a positron emission tomography/[11C]DASB and structural brain imaging study Brain DOI: 10.1093/brain/awq103

Graphics Credit: pubs/teaching/teaching4/Teaching3.html

Labels:

"E",

ecstasy,

ecstasy danger,

MDMA,

serotonin

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Some Background on the Psychedelic Renaissance

Ecstasy, MAPS, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

The psychedelic drugs, new and old, are not only among the most powerful ever discovered, but are also tremendously difficult to study and utilize responsibly. By the mid-1990s, rumors about Ecstasy (MDMA) toxicity were everywhere. Unlike Prozac, but very much like LSD, Ecstasy not only blocks serotonin uptake, but also causes the release of additional serotonin, much the way cocaine and amphetamine cause the release of extra dopamine.

A study conducted by neurologist George Ricaurte at John Hopkins University under NIDA sponsorship seemed to show conclusive evidence of neurotoxic damage to the serotonin 5-HT receptors in the brains of monkeys given large doses of MDMA. A follow-up study of 30 MDMA users (existing users, since researchers didn’t have government permission to give MDMA to test subjects) showed 30 per cent less cerebrospinal serotonin, compared to a control group. However, the Johns Hopkins team did not have any baseline measurements for the MDMA users, and other neurologists raised technical objections about various aspects of the study, including dosage levels. As was often the case in such studies, the monkeys had been given a whopping dose, compared to the typical raver’s dose. Ricaurte insisted that the amount of MDMA consumed by a typical user in one night of raving was possibly enough to cause permanent brain damage. The government estimates that 10 million Americans have taken Ecstasy.

That would seem to be the end of the story, and a sobering lesson for today’s youth—but that is not how it turned out. A few years later, Dr. Charles Grob, psychiatry professor at the UCLA School of Medicine, received the first FDA approval ever given for the administration of MDMA to human volunteers. The result of Grob’s testing was that none of the volunteers showed any evidence of neuropsychological damage of any kind. In testimony before the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which was considering harsher penalties for MDMA possession in 2001, Dr. Grob seriously questioned the methodology of the Ricaurte studies: “It is very unfortunate that the lavishly funded NIDA-promoted position on so-called MDMA neurotoxicity has inhibited alternative research models which would better delineate the true range of effects of MDMA, including its potential application as a therapeutic medicine.” Science retracted its coverage of the Ricaurte findings.

It was eventually discovered that Dr. Ricaurte’s monkeys had been injected with amphetamine, not with MDMA—a discovery that also nullified four other published papers. Dr. Ricaurte explained that some labels had been switched, and a Johns Hopkins spokesperson called the whole thing “an honest mistake.” The basic questions about Ecstasy remain unanswered. Is there a line that separates a conceivably therapeutic dose of Ecstasy for mental ills or addictive ills from a possibly brain-damaging run of several dozen high-dosage trips? Perhaps the permanently altered receptor arrays, if they exist, don’t affect cognition or emotions in any significant way over the long run. Still, the risks of overindulgence appear to be at least potentially higher than the risks of overindulging in LSD or Ibogaine. All of the psychedelics tend to be more self-limiting than other categories of psychoactive drugs, anyway. After two or three days, even the most die-hard raver or LSD head is usually ready to take a break.

Rick Doblin and others at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) are now working with government investigators to pursue MDMA for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. There are reports that very low doses of LSD sometimes have an antidepressant effect. One thing we know for certain is that people on SSRI medications or MAO inhibitors report that their experiences on LSD or Ecstasy are shorter and far less powerful than is typically the case. There appears to be some competition for receptor sites when Zoloft meets LSD. In contrast to the diminished psychedelic experience while on SSRIs, the older norepinephrine-active tricyclics like Tofranil and Norpramine reportedly serve to potentiate the LSD or MDMA experience. None of these combinations is a wise idea, due to uncertainties about the interactions.

Even DMT, which experienced trippers compared to being shot out of a cannon, has returned as a legitimate study subject. Dr. Rick Strassman, then with the University of New Mexico’s School of Medicine, received approval for clinical testing of DMT. Strassman was drawn to the subject because of the molecule’s natural occurrence in the brain (which makes every man, woman, and child in America a drug criminal, chemically speaking). He gave DMT to 60 human volunteers over a study period of five years. Strassman was primarily interested in near-death experiences and mystical experiences. None of the supervised DMT sessions evidently resulted in any detectable harm to the participants. Strassman presents his views on the medical use of DMT in his book, DMT: The Spirit Molecule.

Adapted from The Chemical Carousel: What Science Tells Us About Beating Addiction by Dirk Hanson © 2008, 2009.

Graphics Credit: http://hightimes.com/

Labels:

ecstasy,

LSD research,

MDMA,

psychedelic research,

PTSD

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

How Pure Is Ecstasy?

Dutch study of street MDMA.

For 16 years, the Drugs Information Monitoring System (DIMS) in The Netherlands has gathered and analyzed tablets of purported MDMA sold on the street as Ecstasy. In a research report published in Addiction, Neeltje Vogels and others at the Netherlands Institute for Mental Health and Addiction in Utrecht found that between 70 to 90 % of the samples submitted as MDMA were pure. The most common non-MDMA adulterant was found to be caffeine.

The study covered the years from 1993 to 2008. In the mid to late 1990s, researchers saw an increase in ephedra and methamphetamine in the samples, and sample purity hit an all-time low of 60% in 1997. The years from 2000 to 2004 were the golden era, so to speak, for MDMA purity. “After 2004,” the study authors write, “the purity of ecstasy tables decreased again, caused mainly by a growing proportion of tablets containing meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP).” mCPP belongs to a class of stimulants, the so-called piperazines, that have been banned in several countries (See my post).

As noted on the DrugMonkey science blog, a lack of consistent published data has hampered efforts at studying street MDMA. Tablets for analysis are obtained either from law enforcement—which seizes drugs that may or may not be for sale at the club level--or drug analysis and harm reduction sites. The problem, DrugMonkey writes, is that “perhaps Ecstasy found to result in suspicious subjective effects on the user are submitted to harm reduction sites preferentially.” In other words, people only submit the brown acid.

The Dutch study, on the other hand, obtained samples for testing from capsules seized by club owners and given to the police, who then passed them on to DIMS for analysis. This system helped eliminate the possible bias effect of voluntary submissions.

The study also found that larger tablets, containing 100 mgs or more of MDMA, became increasingly popular starting in 2001.

DrugMonkey, an anonymous NIH-funded biomedical researcher, calls the study “an impressive longitudinal dataset.” The data, he wrote, give us “a good picture of the percentages of MDMA-only across time (higher than certain MDMA fans seem to acknowledge when it comes time to assess medical emergency cases) and the relative proportions of specific contaminants (certain baddies are quite rare.)”

Specifically missing in action most years is the baddy known as PMA, or para-methoxy-amphetamine, which has been implicated in many of the alleged Ecstasy deaths by overheating--a condition known as hyperthermia.

Graphics Credit: National Institute on Drug Abuse

Labels:

club drugs,

Dutch drugs,

ecstasy,

ecstasy danger,

MDMA

Sunday, February 8, 2009

Arguing About Ecstasy

U.K. professor says “E” no riskier than horseback riding.

Professor David Nutt of Bristol University and Imperial College, London, stirred up a hornet’s nest of controversy last week when he compared the dangers of the club drug Ecstasy (MDMA) to people’s addiction to horse riding. In an article titled "Equasy: An overlooked addiction with implications for the current debate on drug harms,” published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, Professor Nutt wrote: "Drug harm can be equal to harms in other parts of life. There is not much difference between horse-riding and ecstasy."

What makes all of this interesting is that Professor Nutt serves as the chairperson of the Home Office's Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), which will rule next week on whether ecstasy should be downgraded to a Class B drug in the British drug classification system. Drug treatment activists and government ministers immediately called for his resignation, saying Nutt was on a "personal crusade" to decriminalize the drug.

The BBC News Service reported that a Home Office spokesperson said recently that the government believed ecstasy should remain a Class A drug. "Ecstasy can and does kill unpredictably. There is no such thing as a 'safe dose'," he said.

Horse-riding accounts for 100 deaths or serious accidents a year in the U.K., according to Nutt. “Making riding illegal would completely prevent all these harms and would be, in practice, very easy to do.” In contrast, recent figures indicate about 30 deaths attributed to ecstasy use in the U.K. last year. “This attitude raises the critical question of why society tolerates - indeed encourages - certain forms of potentially harmful behaviour but not others such as drug use," Nutt wrote.

In an article by Christopher Hope in the Daily Telegraph, Nutt said: "The point was to get people to understand that drug harm can be equal to harms in other parts of life.” He cited other risky activities such as “base jumping, climbing, bungee jumping, hang-gliding, motorcycling," which, he said, were more dangerous than illicit drugs.

An ACMD spokesperson said: "Prof Nutt's academic research does not prejudice the work that he conducts as chair of the ACMD."

According to the Telegraph article, there are 500,000 regular users and between 30 million and 60 million ecstasy pills in circulation in the U.K.

In a letter published by the Journal of Psychopharmacology two years earlier, Professor Nutt used a more apt comparison to make the same point:

“The fact that alcohol is legal and ecstasy not is merely an historical accident, not a science-based decision. Alcohol undoubtedly kills thousands more people each year than ecstasy.... Many relatively ill-informed and indeed innocent young people will continue to die and many more will end up with the destructive consequences of alcohol dependence or physical damage. If the same effort currently used to deter ecstasy use was put toward reducing alcohol misuse the situation might improve.”

Photo Credit: Foundation Antidote

Labels:

"E",

club drug,

ecstasy,

ecstasy danger,

MDMA,

X addiction

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)